Toronto scientists help create AI-powered bot that can play chess like a human

If you know anything about the intersection of chess and technology, you're likely familiar with IBM's famous "Deep Blue" — the first ever computer to beat a reigning (human) world champion at his own game back in 1997.

A lot has happened in the world of artificial intelligence since that time, to the point where humans can no longer even compete with chess engines. They're simply too powerful.

In fact, according to the authors of an exciting new paper on the subject, no human has been able to beat a computer in a chess tournament for more than 15 years.

Given that human beings don't generally like to lose, playing chess with a purpose-built bot is no longer enjoyable. But what if an AI could be trained to play not like a robot, but another person?

Meet Maia, a new "human-like chess engine" that has been trained not to beat people, but to emulate them, developed by researchers at the University of Toronto, Cornell University and Microsoft.

Using the open-source, neural network-based chess engine Leela, which is based on DeepMind's AlphaZero, the scientists trained Maia using millions of actual online human games "with the goal of playing the most human-like moves, instead of being trained on self-play games with the goal of playing the optimal moves."

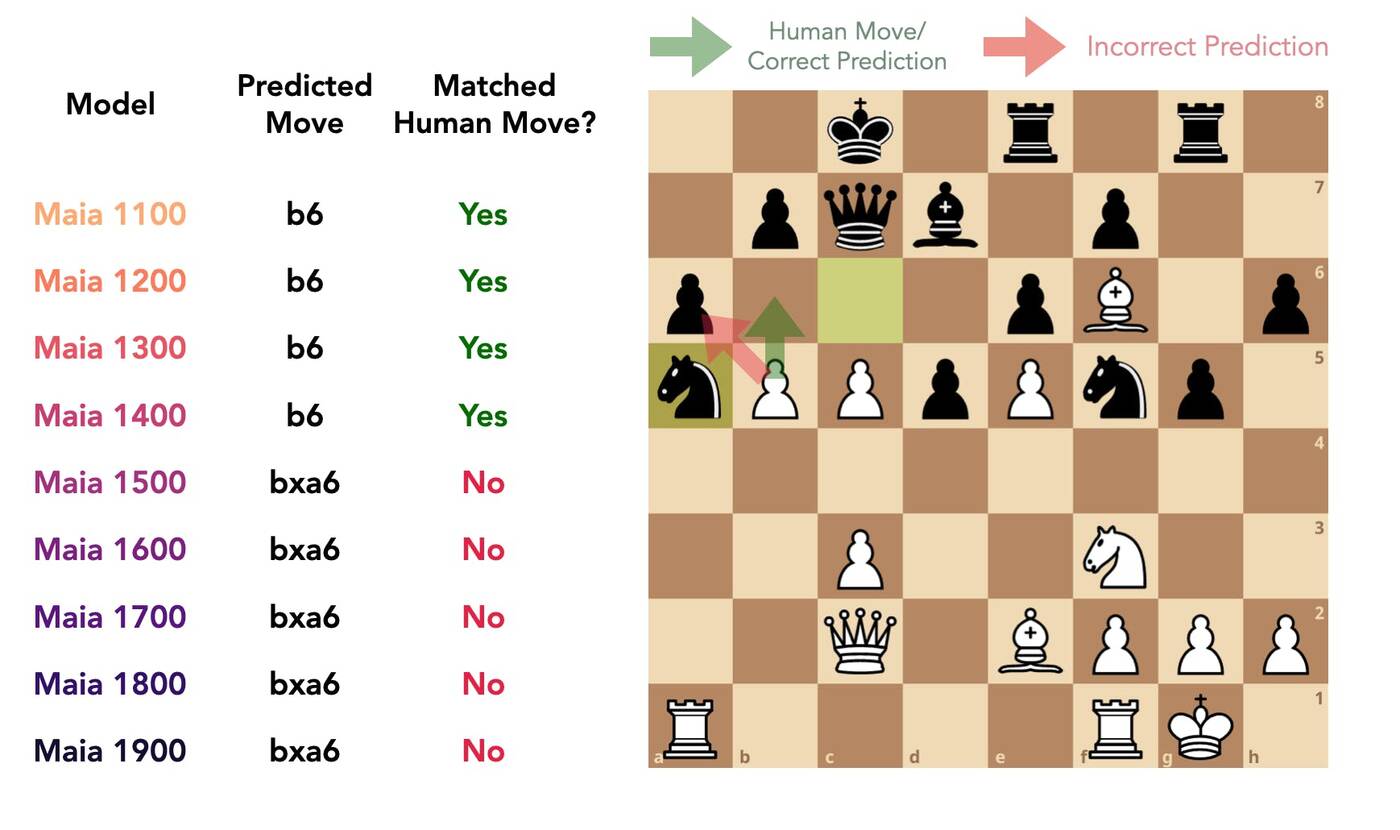

Nine different Maias were actually developed to account for varying skill levels, all of them producing different (but incredibly positive) results in terms of how well they could predict the exact moves of human players in actual games.

According to the paper, which is co-authored by U of T's Ashton Anderson, Maia now "predicts human moves at a much higher accuracy than existing engines, and can achieve maximum accuracy when predicting decisions made by players at a specific skill level in a tuneable way."

Maia takes skill level into account when predicting which moves its human opponents will take. Here, the chess engine predicts that people will stop playing a specific wrong move when they're rated around 1500. Image via the Maia team.

Cool? Certainly — and the project is already helping online chess buffs play more enjoyable matches. But the implications of the research actually go far beyond online games.

The root goal in developing Maia, according to the study's authors, was to learn more about how to improve human-AI interaction.

"As artificial intelligence becomes increasingly intelligent — in some cases, achieving superhuman performance — there is growing potential for humans to learn from and collaborate with algorithms," reads a description of the project from U of T's Computational Social Science Lab.

"However, the ways in which AI systems approach problems are often different from the ways people do, and thus may be uninterpretable and hard to learn from."

The researchers say that a crucial step in bridging the gap between human and machine learning styles is to model "the granular actions that constitute human behavior," as opposed to simply matching the aggregate performance of humans.

In other words, they need to teach the robots not only what we know, but how to think like us.

"Chess been described as the 'fruit fly' of AI research," said Cornell professor and study co-author Jon Kleinberg in a news update published by the American univeristy this week.

"Just as geneticists often care less about the fruit fly itself than its role as a model organism, AI researchers love chess, because it's one of their model organisms. It’s a self-contained world you can explore, and it illustrates many of the phenomena that we see in AI more broadly."

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments