The history of the most spectacular theatre Toronto probably ever had

Toronto's first building purposefully constructed to house a theatre was the Royal Lyceum, opened by John Ritchie on Sept. 25, 1849.

It was behind a row of buildings on the south side of Adelaide Street West, between Bay and York Streets.

Patrons entered the theatre from King Street, through Theatre Lane, where there was an archway between 99 and 101 King (where First Canadian Place is now).

It was the city's first opera house, though it offered more than opera, as it featured plays, groups of actors, strolling musicians, soloists and elocutionists.

Prior to the theatre being built, such entertainment was generally held in taverns, small converted temporary premises or hotel dining rooms.

Watercolour of the south facade of the Royal Lyceum, from the collection of the Toronto Public Library.

The Royal Lyceum possessed a proper stage with stage lights, an orchestra pit, dressing rooms and a balcony.

Unfortunately, the Royal Lyceum burned in 1874, but the year before, a new company had been created to construct another theatre — the Grand Opera House.

It was to be erected at 9-15 Adelaide Street West, a short distance west of Yonge Street.

The new venue was to be managed by Charlotte Nickinson, a retired actress. Its architect was Thomas R. Jackson of New York, who designed the Toronto theatre in the Second Empire style, with mansard roofs atop its east and west wings, connecting sections and the tower.

The four-storey theatre was constructed of brick and stone, with wooden joists to support the interior walls and floors.

Its interior was elaborately trimmed and its ornate gas lamps ignited by batteries. On the first floor, facing Adelaide Street, on either side of the theatre's arched entranceway, were shops that were rented.

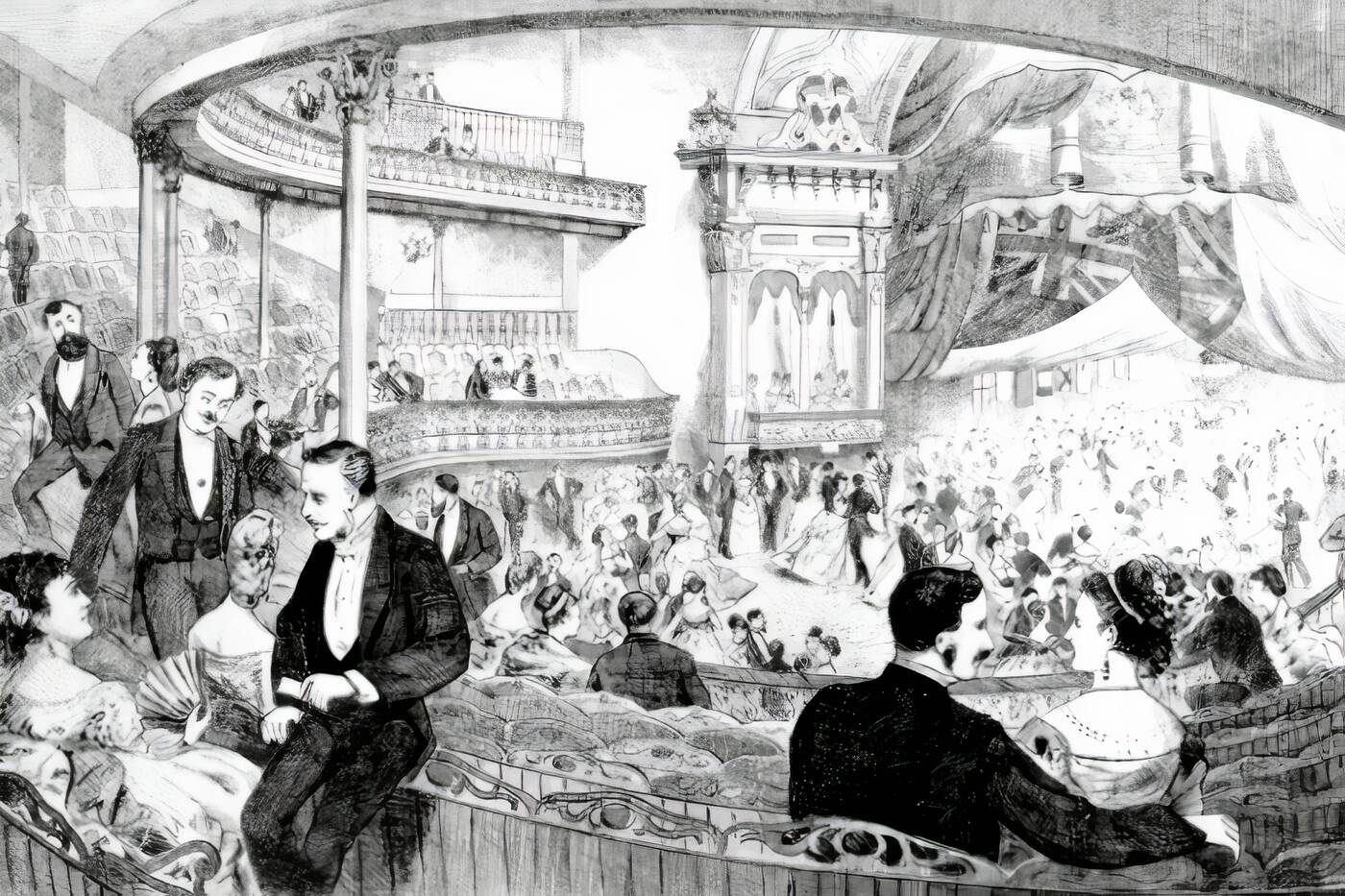

Interior of the Grand Opera House, Canadian Illustrated News, Canada Archives.

The floors above the shops contained offices that were also rented. The funds derived from the shops and offices helped defray the expenses of operating the opera house.

The theatre's arched entranceway led patrons into to a plush reception foyer, 50 feet in depth.

Beyond it was the main foyer where the ticket booth and refreshment bars were located. Stairs on the east and west sides of the foyer allowed patrons to ascend to the dress circle and the two balconies, similar to the Royal Alexandra Theatre of today.

The theatre's domed auditorium accommodated 1,323 patrons.

On the main floor (orchestra section) and in the balconies, people sat on chairs that folded to allow access to the other seats in the row. This was a new feature not yet common in Toronto.

The stage was of sufficient size to allow large-scale productions, as it was 53 feet wide and 65 feet deep. In front of the stage was a sunken orchestra pit. The building was steam heated.

The Grand Opera House opened on Sept. 21, 1874, with a gala that attracted the city's elite.

Grand Old Opera House Interior. Photo via Hamilton Public Library.

The evening's feature performance was Richard Sheridan's 18th-century comedy, School for Scandal, with the theatre's manager, Charlotte Morrison, in the role of Lady Teazle.

When the opera house held grand balls, the seats in the orchestra section were covered with a wooden temporary floor to allow people to dance the night away within the magnificent theatre.

However, despite it being well attended, critically acclaimed and highly popular, the theatre was not a financial success.

In 1876, it was sold in an auction to Alexander Manning. Three years later, the building was badly damaged by fire.

The exterior walls had not been damaged, but the interior was gutted. Manning hired the architectural firm of Lalor and Martin and it was rebuilt in a mere 51 days.

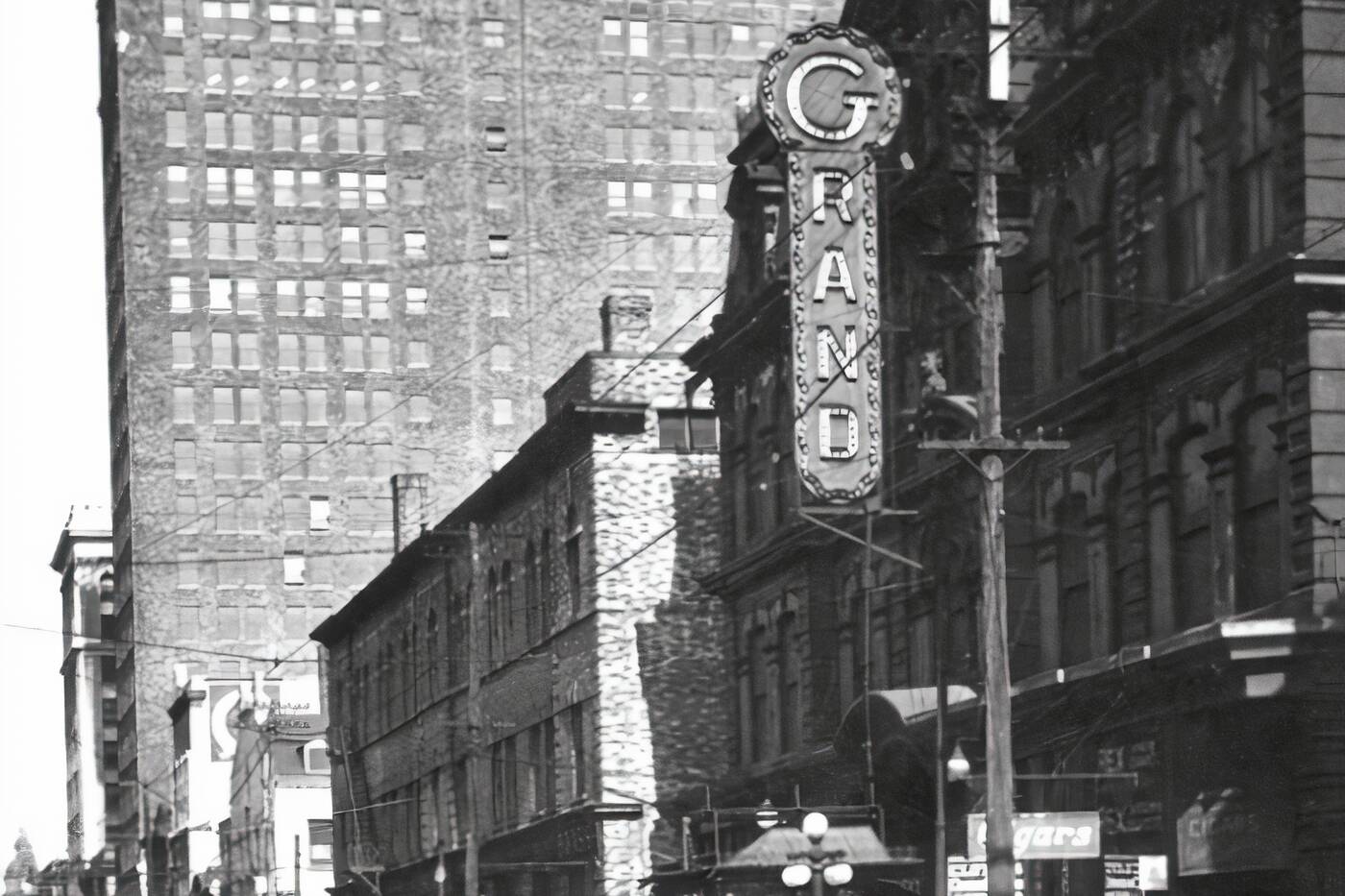

Looking east toward Yonge in 1924. Photo via Toronto Archives.

The new architects' designs were faithful to the original plans except that the seating was increased to 1,750. The grand reopening occurred on Feb. 9, 1880 with a production of Romeo and Juliet.

During the years, famous actors who were on its stage included Maurice Barrymore (father of Lionel and Ethel, great-grandfather of Drew) and Sarah Bernhardt. For the next two decades, Toronto's theatre scene focused on the Grand Opera House.

In 1919, Ambrose Small, the theatre's manager, disappeared along with a considerable amount of cash.

His body was never found and the case remains unsolved. During the early years of the 20th century, its importance diminished due to competition from the Royal Alexandra and the Princess of Wales Theatre on King Street.

Finally, the Grand Opera House closed, and it was demolished in 1927.

Looking east toward Yonge in 2020. Photo via Google Street View.

Doug Taylor was a teacher, historian, author and artist who wrote extensively about Toronto history on tayloronhistory.com. This article first appeared on his site on March 14, 2016 and has been republished here with the permission of his estate. The article has been modified slightly.

Hamilton Public Library, with files from Melody T.C. Lau.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments