This is what the Eaton's catalogue looked like over the years in Toronto

The COVID-19 pandemic, and, indeed, the digital age, have changed the way that we shop. However, we can trace the origins of online shopping back several decades throughout Canadian history.

Mail order catalogues are online shopping's ancestor, and one particular catalogue stands out in Canadian history. The Eaton’s catalogue had many nicknames over the course of its 92-year distribution run. It was known as the Bible, the Homesteaders’ Bible, the Want Book, the Wishing Book, and, more simply, the Book.

The Eaton's catalogue

In 1884, industrial and retail magnate Timothy Eaton unveiled his Eaton’s catalogue at the Canadian National Exhibition, distributing it to visitors. It was a 32-page pink booklet that showcased some of the Eaton’s store’s more popular items.

The next year, a small 6-page booklet announced the creation of Eaton’s own mail order department. Although the Eaton’s catalogue was not the first of its kind in Canada, it was the first one managed by a Canadian retail store.

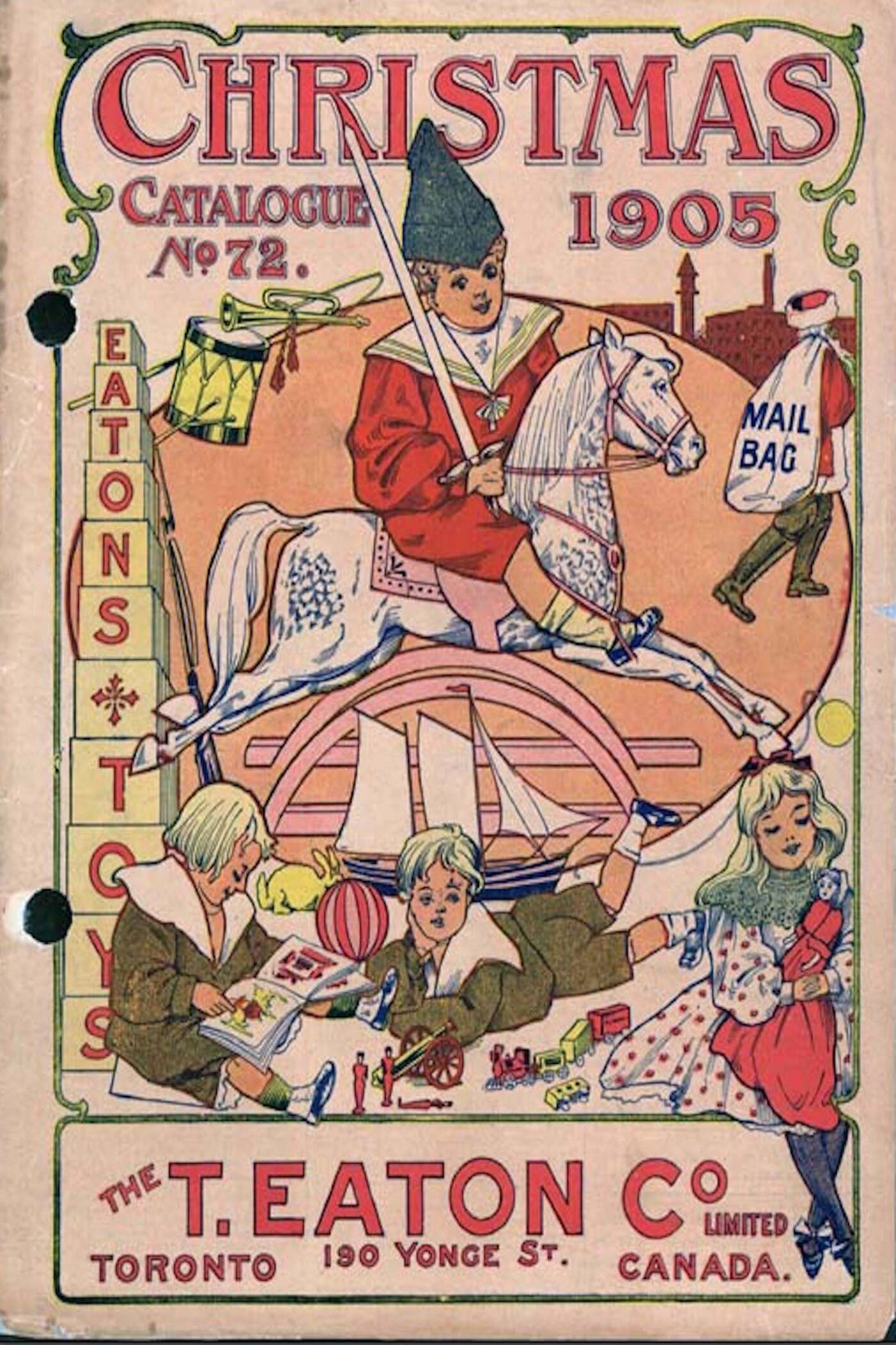

The cover of the Eaton's Christmas catalogue in 1905. Courtesy Government of Ontario.

Existing Eaton’s customers were promised a gift in exchange for addresses and contact information of their friends and neighbours. By 1896, Eaton’s was sending out 135,000 packages by post and 74,000 packages by express mail annually.

The Eatons gradually expanded their retail empire, thriving under the leadership of Timothy Eaton’s son and successor to the business - John Craig Eaton. To reach more rural prospective customers, Eaton’s created unique catalogues for people located in both the Prairies and the Maritimes.

Demand for mail orders increased: in 1903 a separate building was constructed to help fulfill mail orders at Eaton’s flagship store in Toronto. Soon, Eaton’s outposts began to crop up in other parts Canada. A full-service Eaton’s store was built in Winnipeg in 1905 and another soon followed in Moncton beginning in 1918.

Women's fur coats for sale in the Eaton's 1920-1921 Fall and Winter catalogue. Courtesy Toronto Public Library.

In the early days of the catalogue domestic items and women’s clothing graced the catalogue’s pages. Later on, menswear was advertised. This was followed by ads for housewares, agricultural equipment, musical instruments, toys, books, and appliances. By the 1920s, one could even buy building materials for prefabricated houses and barns from the catalogue.

Personal shoppers at the Eaton's department store

People who have been online grocery shopping during the pandemic will no doubt be familiar with personal shoppers handling their orders. Eaton’s relied on personal shoppers to fulfill mail orders.

Usually young women, personal shoppers at Eaton’s would be expected to fulfill orders with precision and a keen eye for detail.

These personal shoppers (according to the catalogue) "must have besides a keen, clear, personal inspiration - something more than exact machinery - insight, power to look behind ink and paper and catch the living person to be served; ability to make a mental photograph of the writer, and read between the lines the thought that created the words."

Wallpaper samples in the Eaton's catalogue from the Fall and Winter 1920-1921 edition. Courtesy Toronto Public Library.

Occasionally, personal shoppers would have to make substitutions, as they would often work with scant information about what customers wanted.

How ordering from a mail order catalogue worked

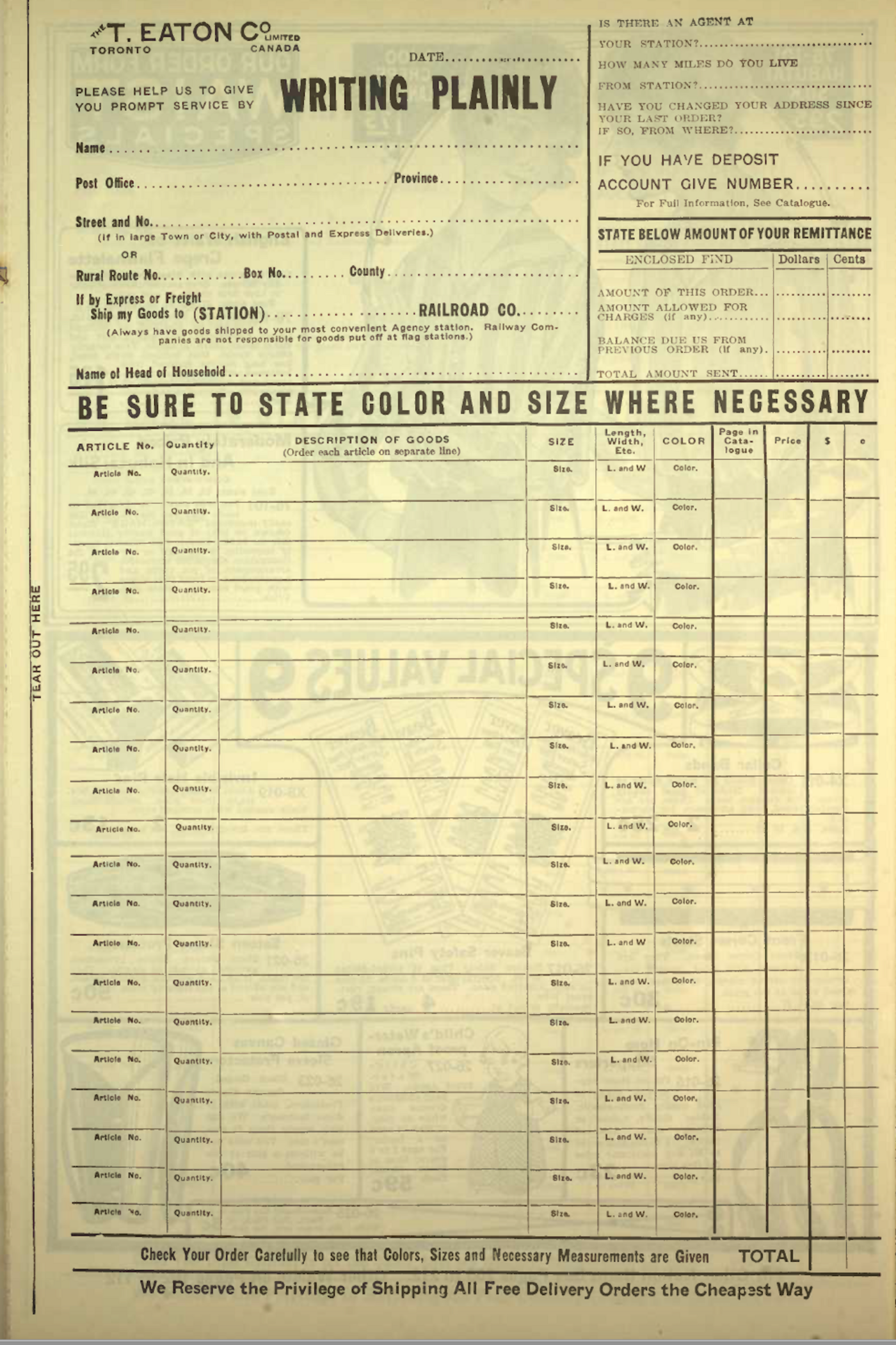

Customers could mail in bank drafts and money orders to purchase goods. The catalogues included handy information on how to purchase and write mail orders, along with information about returns (returns travelling by freight, for example, would need to be accompanied by railway receipts if they were to be accepted by the store).

A mail order form from the Eaton's catalogue, Fall and Winter edition of 1920-1921. Courtesy Toronto Public Library.

Customers could also charge purchases to the Eaton Account, which functioned similar to a credit card with monthly terms and a credit service charge.

Measuring guides for both clothing and home furnishings were found either in the back of the catalogue or alongside the list of the catalogue’s offerings.

These massive catalogues would often be 500 to 800 pages long. Eaton’s advertised that it paid regular shipping charges on most items.

Customers who spoke a language other than English were encouraged to write to Eaton’s in their native language: a catalogue from 1975 advertised that it accepted mail from those who spoke Italian, Finnish, Latvian, Polish, Spanish, German, and Dutch.

The catalogue was translated into French beginning in the early twentieth century, and customers could write to the catalogue in French and receive a response in the same language.

Grocery delivery with Eaton's

The Eaton’s Grocery Catalogue is analogous to today’s grocery delivery and online ordering services. The Grocery Catalogue promised “all the advantages of city shopping” and was backed by a quality guarantee; Eaton’s would refund money if the purchase was not satisfactory.

An ad for the Grocery catalogue in the Fall and Winter 1920-1921 edition of the catalogue. Courtesy Toronto Public Library.

Reusing the catalogue

What could one do with an out-of-date catalogue? Children would cut up the images to use as paper dolls or as crafting items for school projects.

The Eaton’s catalogue was oftentimes used as a tool by newcomers to Canada to gain facility with the English language. Elementary school teachers would use the Eaton’s catalogue in their language lessons with young students.

People could also use the catalogue for other practical purposes: to help insulate drafty cabins and houses, and, less glamorously, for toilet paper.

The decline of Eaton's

Eaton’s published its last catalogue in the summer of 1976. As Canada gradually grew more urban, Canadians had access to many more local stores. By the mid-1960s, it was estimated that over half of Canada’s population lived within a thirty-minute drive to an Eaton’s store.

The news of the mail order department’s closure sent shockwaves throughout Canada: 9,000 people lost their jobs.

Economic hardships in the 1980s and 1990s pushed Eaton’s closer to bankruptcy. Bigger American competitors, like Walmart, were coming into the Canadian market. Traditional department stores overall were being eclipsed by big-box stores in the suburbs.

By 1999, the company, which had been in operation for over 130 years, declared bankruptcy. Sears would go on to acquire Eaton’s corporate assets. The name of the company lives on in the Eaton Centre in Toronto and the Eaton Centre in Montreal.

The government of Canada has preserved a number of Eaton's catalogues in its mail order catalogue database.

T. Eaton Co. Ltd.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments