A very personal history of Victoria Day 1945

A hundred years after Victoria Day became a legal holiday in what was not yet even Canada, on the Friday before the Victoria Day holiday in 1945, my dad splurged and spent three dollars on firecrackers at a store on Oakwood Avenue.

Among his purchases were Pinwheels, Comets, Whiz-bangs, Fountains, Sparklers, and a Burning Schoolhouse. However, our favourites were the Roman Candles, as we knew that they rocketed high into the night sky, exploding in bursts of sparkling colour while creating loud crackling sounds.

On the 24th, as the sun commenced dipping slowly toward the western horizon, our anticipation increased. We gathered on the veranda, and anxiously waited for night skies to blanket the city.

This was a big day.

Photo of Queen Victoria in 1837 from Gandalf's Gallery.

Queen Victoria, born 24 May 1819, ascended the British throne in 1837 at the age of 18 on the death of her uncle, King William IV.

The holiday was originally observed on the day on which it occurred, but if May 24 were on a Saturday or Sunday, the holiday was celebrated on the following Monday.

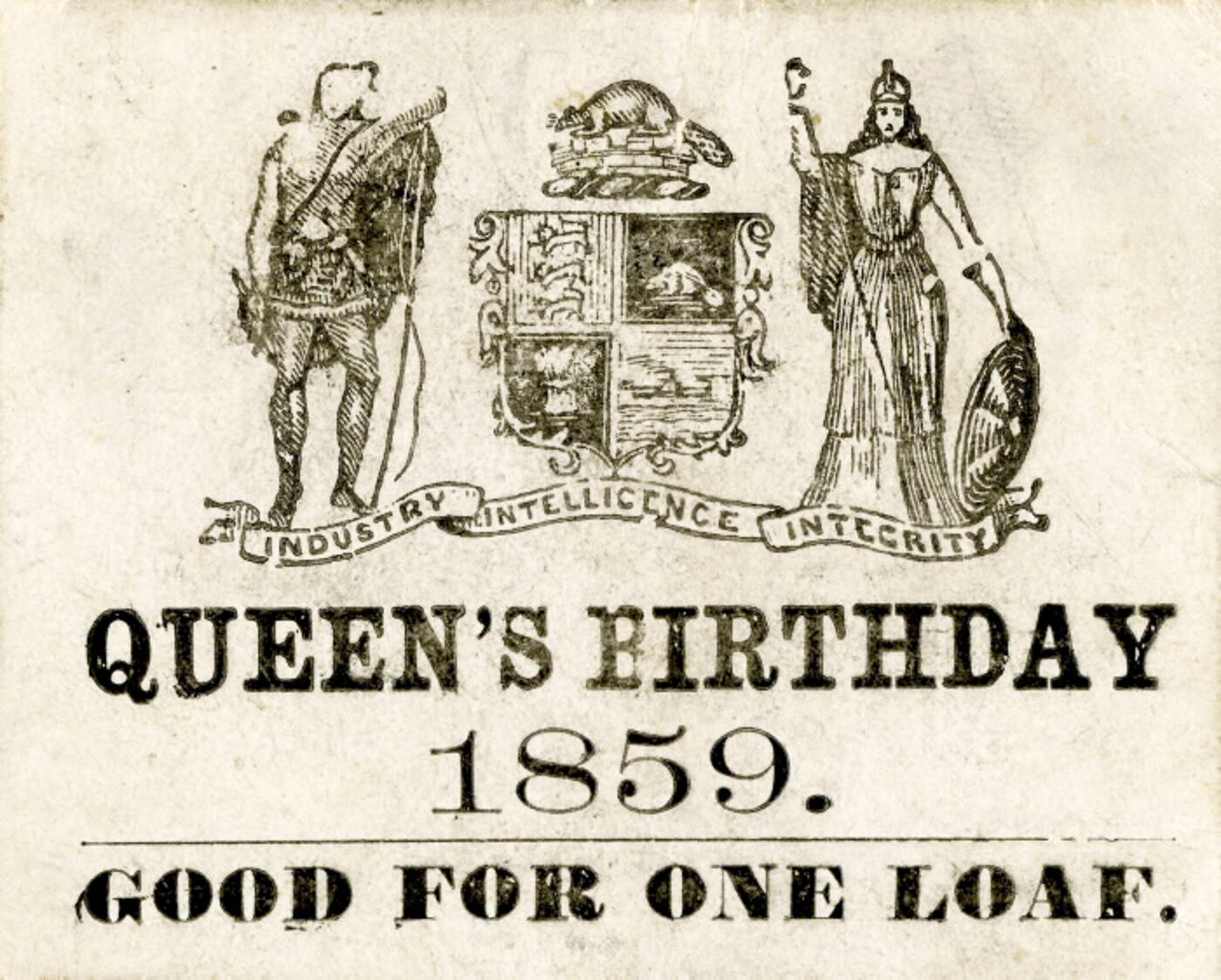

A rare celebratory coupon, good for some Victoria Day bread. Via Toronto Public Library.

The legislature of Canada West, the province later renamed Ontario, established the monarch's birthday as a work holiday in 1845.

This was an act of true homage to the Queen, as even Christmas was not a legal holiday for workers in 1845. It was solely at the discretion of the employer.

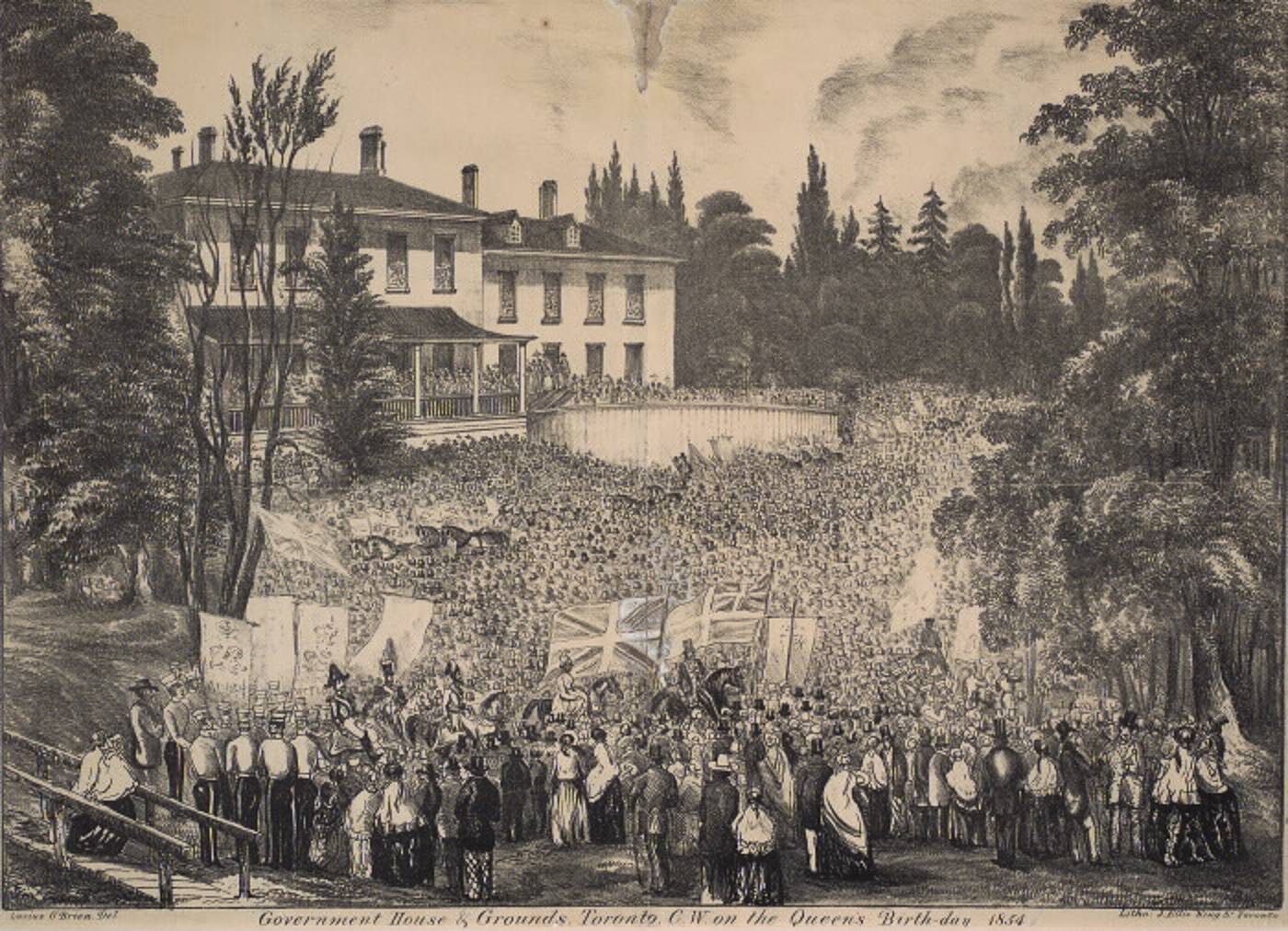

A Victoria Day gathering at Government House in 1854, at the southwest corner of King and Simcoe. Via Toronto Public Library.

But for me, in 1945, it was about the fireworks.

There were a few public displays in the parks, but none within easy travelling distance of our home. As a result, the families in our neighbourhood purchased their own fireworks, usually at a corner store that sold penny candy.

When I was a child, we referred to Victoria Day as “Fire-Cracker Day.” There were very few public displays of fireworks, and even if there had been, it would have required a streetcar ticket to travel to the site.

We lived in the township of York and on Victoria Day, we sat on our front veranda and watched as our dad ignited the firecrackers.

Victoria Day didn't change much between 1945 and when these kids were waving their holiday sparklers in Toronto in 1990. Via Toronto Public Library.

As it darkened further, we lit the Whiz-bangs, also referred to as “squibs,” which were small firecrackers, and tossed them into the street, where they exploded like gunshots. We waved sparklers in the air forming patterns of light.

Finally, when it was totally dark, my dad set-off the serious firecrackers. Showers of flames burst from the curbs beside the sidewalk and rocket flares exploded, the scene reminiscent of a battlefield. My brother and I cheered as the Burning Schoolhouse was demolished in flames.

Neighbours staggered their displays so that not everyone’s exploded at the same time. All up and down Lauder Avenue, for over an hour, the night sky was broken with bursts of light.

When our family had exhausted our supply, we watched the neighbours' contributions. Adults supervised carefully, to prevent a mishap.

My brother and I were entranced by the fireworks, but my brother loved them the most. Even as an adult, he travelled considerable distances throughout the city to observe displays.

On the night of May 24, 1945, I sat beside him and shared the excitement. After we were sent upstairs to bed, we crept into my parents’ bedroom and gazed out the window overlooking the street to observe the last of the explosions.

A few teenagers had acquired their own firecrackers and were setting them off after the families with young children had retired from the scene. The next day, in the curbs beside the sidewalks, my brother and I observed the charred remains of the previous night’s revelries.

Similar to "the next-day" pumpkins and discarded Christmas trees, they were reminders of a glorious time well spent.

Doug Taylor was a teacher, historian, author and artist who wrote extensively about Toronto history on tayloronhistory.com. This article first appeared in different forms on his site on May 22, 2011 and May 21, 2016 and has been republished here with the permission of his estate. The article has been modified slightly.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments