The history of the Allan Gardens Conservatory in Toronto

The greenhouses in Allan Gardens are among the city's relatively unknown treasures.

Hidden amidst the foliage of the park, many motorists in downtown Toronto speed past them daily as they navigate the busy streets that surround them, but very few ever take the time for a visit.

Allan Gardens is bounded by Jarvis on the west, Sherbourne on the east, Carlton on the north and Gerrard on the south. Their official postal address is 160 Gerrard St. E.

The greenhouses are open to the public every day of the year and there's no admission charge.

On frosty winter days, the greenhouses provide a cozy oasis of lush growth and warm humid air that remind us of southern climes. In summer, the plants in the park outside the greenhouses pale in comparison to those growing indoors.

Allan Gardens has an interesting history from the 19th century. Before the present-day structures were built, there were pavilions containing greenhouses.

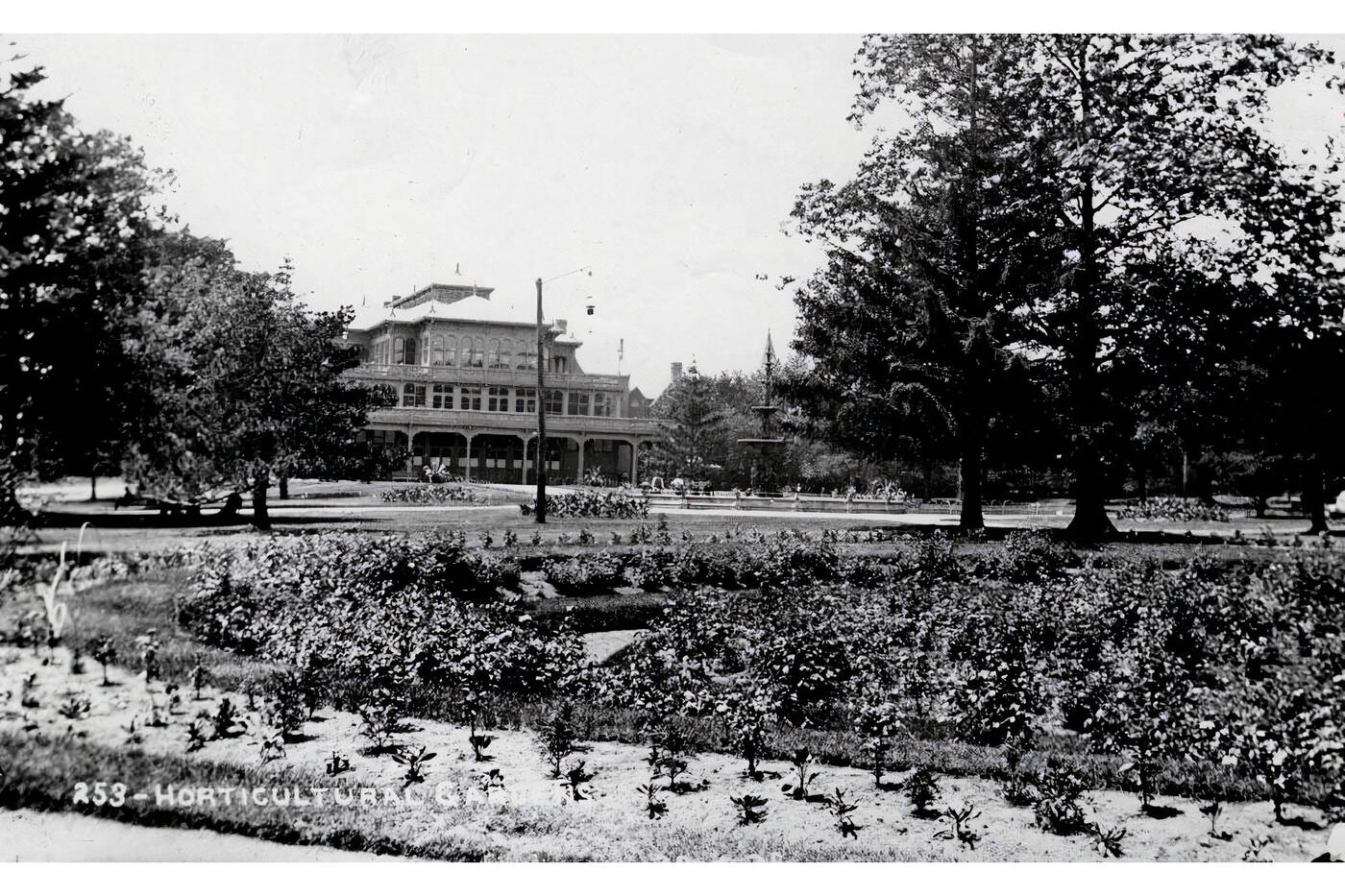

View looking west along the walkway that led to the pavilion from the 1870s. Photo from Toronto Public Library.

The story of Allan Gardens is interwoven with the history of the Toronto Horticultural Society, founded in 1834 — the year of Toronto's birth as a city.

John Colborne, the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada (1828-1836), was the society's benefactor. Colborne Lodge in High Park is named after him.

The society's purpose was to introduce improved species of plants to the province, especially fruits and vegetables.

Also interwoven into the history of Allan Gardens is George William Allan, a prominent lawyer and politician who served as Toronto's 11th mayor from 1854 to 1856.

In 1858, two years after his retirement from city council, he donated five-acres of land to the Horticultural Society.

The society gratefully accepted Allan's generosity and the deed to the land changed hands on March 14, 1860.

The newly created park, referred to as the Horticultural Gardens, was to become a botanical garden and a pleasant green space for strolling and picnics.

The interior of Allan Gardens' pavilion in the 1890s. Photo from Toronto Public Library.

On September 11, 1860, the Prince of Wales, later to reign as King Edward VII, visited Toronto and officially opened the gardens.

On the grounds, he planted an oak tree that grew to an enormous size, providing pleasant shade for many decades from the heat of Toronto's summer sun.

Unfortunately, in 1938, the gigantic tree was struck by lightning and the remaining sections were removed.

On the same royal visit in 1860, the wife of George William Allan also planted a tree, which for safety reasons was cut down in 1956.

Throughout the remaining decades of the 19th century, Allan Gardens was one of the most popular attractions in the city.

To enlarge the park, the City of Toronto bought a parcel of land from Mr. Allan. It surrounded the property that he had originally donated.

The funds for the purchase were derived from the city's Walks and Gardens funds.

The city then leased the newly acquired land to the Toronto Horticultural Society for a nominal sum. A condition was written into the agreement that the grounds were to be publicly accessible and free of charge eternally for everyone.

The pavilion on June 6, 1895, the Rosary (rose garden) in the foreground. Photo via Toronto Archives.

In 1864, to attract more visitors, the Horticultural Society spent $6,000 on improving the park and constructing a pavilion with greenhouse space where plants could be grown indoors.

However, despite the pavilion being very popular with visitors, it was not well maintained.

Also, its size had become inadequate for the requirements of the venue. In 1878, only 14 years after it was built, it was demolished to enable the construction of another pavilion.

To finance it, a loan of $20,000 was secured by the Society by offering the park’s grounds as security.

In the summer of 1879, the new Horticultural Pavilion opened. Designed by the Toronto architectural firm of Langley, Langley & Burke, its impressive dimensions were 75-feet by 120-feet.

It was constructed mainly of wood and iron, with many large glass surfaces to allow sunlight to enter the interior. Its design was inspired by the Crystal Palace built for the Great Exhibition of 1862 in London, England.

Photo taken in 1896 of the east (front) facade of the pavilion. The fountain designed by Langley, Langley and Burke is visible in the foreground. Photo via Toronto Archives.

Toronto’s pavilion was located a short distance west of the previous one, midway between Carlton and Gerrard. A 45-foot by 48-foot conservatory was later added to its south side.

The stage of the pavilion’s auditorium accommodated as many as 200 performers. It was considered one of the premier facilities of its kind in Canada, competing with the St. Lawrence Hall on King Street East for the honour of being the cultural centre of the city.

From the day the pavilion was inaugurated, it was in great demand for concerts, gala balls, conventions, public lectures and of course, flower shows. In 1882, Oscar Wilde lectured in the Pavilion Hall.

The architects who designed the second pavilion were also commissioned to erect a 25-foot stone basin fountain, with a 45-foot diameter. It was constructed on the same site as the former pavilion.

Allan Gardens' fountain in 1884. Photo via Toronto Public Library.

The fountain no longer exists, and I have been unable to discover when it was dismantled. Photos reveal that it was still there in 1925.

Today, there is a similar fountain in St. James Park on King Street East, though it is on a much smaller scale.

In 1888, despite the popularity of the gardens, the society was bankrupt. As a result, the City of Toronto assumed ownership of the property and its assets, paying off the $35,000 mortgage.

The city then constructed a decorative fence around the park and replaced the gas lamps with those that were electrified.

In 1894, the City allocated considerable funds to modernize the pavilion. A refreshment room was added and the old conservatory was replaced with a larger facility that was 90-feet by 61-feet.

Its architect was Robert McCallum, who served as the City Architect of Toronto from 1903 until his forced resignation in 1913.

The structure was an ornately grand four-storey building, with fancy architectural trim and sweeping verandas.

In 1901, the name of the park was changed to Allan Gardens, in honour of the man who had donated the land to originally create the park. Unfortunately, on June 6, 1902, a disastrous fire destroyed the pavilion, along with sections of the new conservatory.

Robert McCallum was again hired to design its replacement. After the fire, for the next few years the only sections of the pavilion that were open to the public were those that survived the flames.

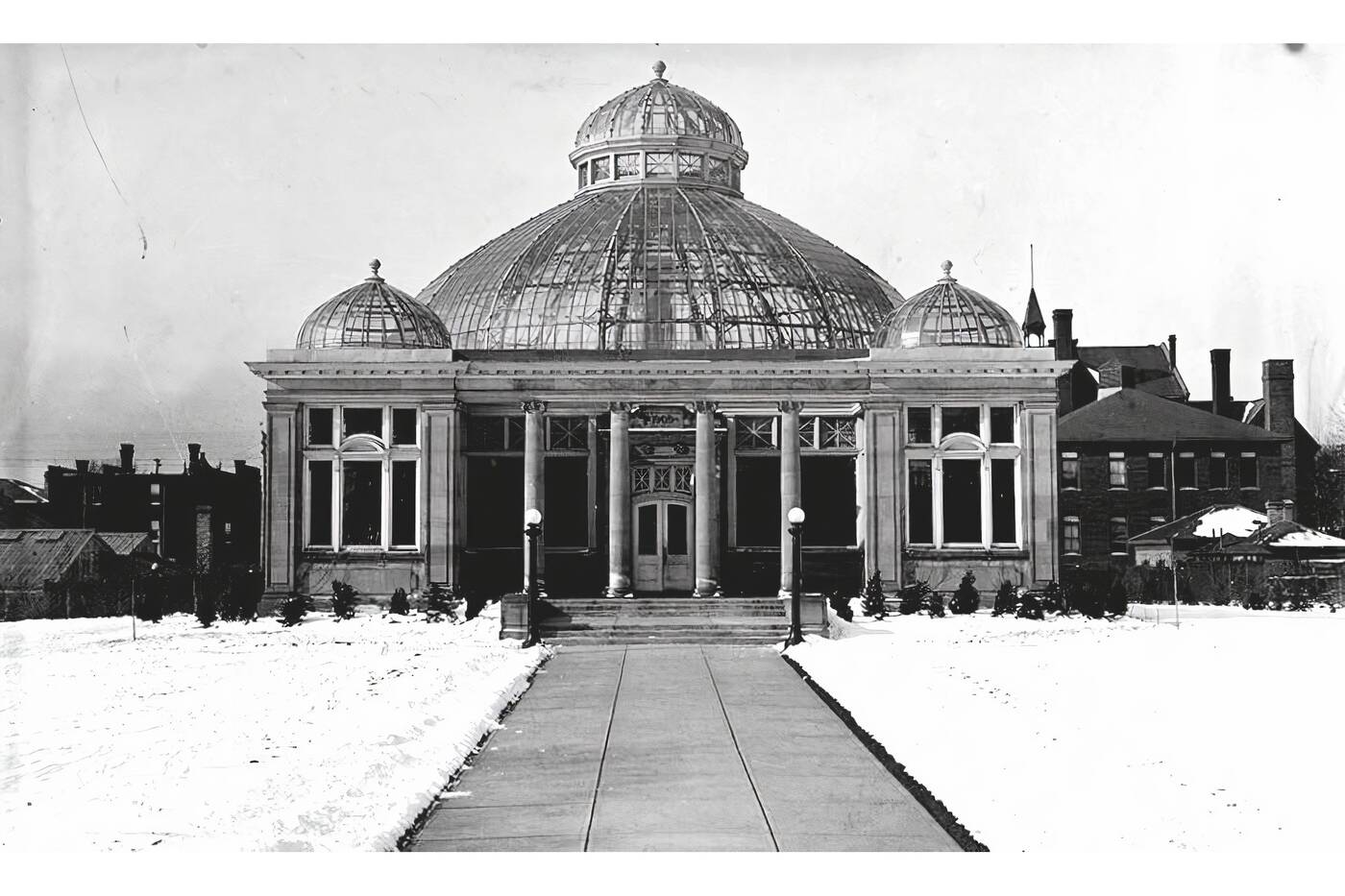

View of the Palm House that opened in 1910. Photo taken in February 1913. The greenhouses on either side of it had not yet been built. Photo via Toronto Archives.

It was eight years before a new pavilion appeared. Inaugurated in 1910, it contained an impressive collection of native and foreign specimens, including rare orchids and other exotic plants and palms.

Reflecting popular trends of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century, the gardens and pathways in the park were designed in a symmetrical manner.

This sprawling greenhouse facility still exists in Allan Gardens today, its main building named the Palm House. The latter structure is classically proportioned — possessing an enormous dome.

During the 1920s, the greenhouses were expanded when two new display structures were added to the Palm House. They were attached to the north and south sides of it.

In 1957, an additional greenhouse, possessing building extensions, was constructed, expanding the conservatory's display space. The adjacent garden areas were also reconstructed.

Photo by Jeff Hitchcock.

In 2003, the University of Toronto’s former botany education facility greenhouse, built in 1932, was dismantled and relocated to Allan Gardens to accommodate the construction of the university's new pharmacy building.

Doug Taylor was a teacher, historian, author and artist who wrote extensively about Toronto history on tayloronhistory.com. This article first appeared on his site on February 16, 2019 and has been republished here with the permission of his estate. The article has been modified slightly.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments