These neighbourhoods had the highest eviction rates in Toronto pre-pandemic

Evictions across Toronto and throughout Ontario have been taking place at an unprecedented rate as many tenants have lost income and employment during the pandemic and accumulated rent arrears as a result, and a new study from the Wellesley Institue aims to highlight and address the impacts of these residential evictions.

The data brief, titled Where eviction applications are filed: Ward distribution of eviction applications in Toronto and written by Scott Leon, examines where eviction applications were filed prior to the pandemic as well as how these evictions negatively impact population health and well-being.

"The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the urgency to understand and address residential evictions. Evictions have the potential to disrupt the public health responses to COVID-19, magnify the associated recession, and disrupt tenants' lives," writes Leon in the brief.

"To adequately address evictions, it's important to first understand where eviction applications are taking place."

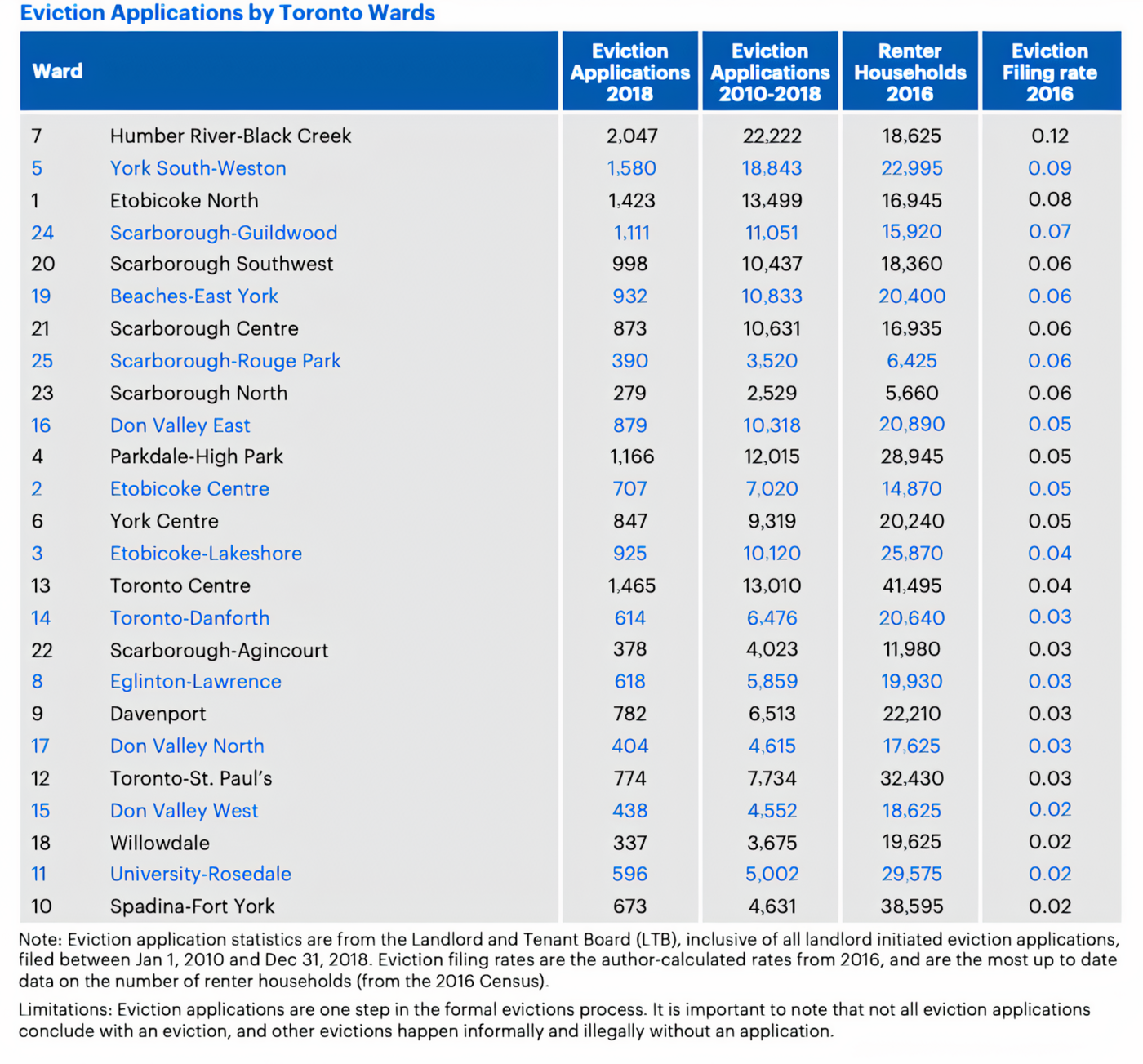

According to the data from 2016, eviction filing rates (the total number of formal eviction applications divided by the number of renter households in each ward) were highest in a number of inner-suburban Toronto wards, including Humber River-Black Creek (ward 7), York South-Weston (ward 5), Etobicoke North (ward 1), Scarborough-Guildwood (ward 24) and Scarborough Southwest (ward 20).

These wards saw respective eviction filing rates of 0.12 per cent, 0.09 per cent, 0.08 per cent, 0.07 per cent and 0.06 per cent in 2016, and a total of 2,047, 1,580, 1,423, 1,111, and 998 eviction applications were filed in these same wards in 2018, respectively.

In comparison, Spadina-Fort York had large numbers of renters (38,595), a moderate number of eviction applications (673) and therefore a low eviction filing rate of just 0.02 per cent.

Previous Wellesley Institute research found that areas in Toronto where equity-seeking groups live had disproportionately higher eviction filing rates, according to the brief, indicating that areas with higher renter poverty had 2.5 times higher eviction filing rates on average.

Previous Wellesley Institute research found that areas in Toronto where equity-seeking groups live had disproportionately higher eviction filing rates, according to the brief, indicating that areas with higher renter poverty had 2.5 times higher eviction filing rates on average.

"Independent of this association, census tracts where a greater percentage of renters self-identify as Black had twice the eviction filing rates," reads the brief. "The analysis in this data brief supports this. The wards where the highest number of Black Torontians live also had the highest numbers and rates of eviction applications (Wards 1, 5, and 7)."

This is also true of neighbourhoods that have been disporpotionately impacted by COVID-19, which is hardly shocking considering the Wellesley Institute says prior research on evictions has shown them to have detrimental impacts on tenants' health.

The brief explains that a 2017 research review found that people facing the involuntary loss of housing have worse health outcomes, including both mental (depression, anxiety, psychological distress, suicide) and physical (self-reported health, blood pressure).

"Achieving a healthier Toronto means understanding, addressing, and ultimately reducing the burden of residential evictions," writes Leon.

The brief also includes two recommendations for better protecting tenants from evictions, the first of which is that the city and the province provide increased and enhanced eviction prevention services located near tenants who are facing the threat of eviction in consultation with community leaders and tenants' groups.

"This will likely make these services more effective, and also improve equity by minimizing the impact on those already suffering the threat of eviction," says Leon.

The Wellesley Institue also advises that all three levels of government should introduce an "arrears protection program" that works in the interests of both tenants and landlords to help cover unpaid rent and avoid costly evictions.

"The federal government has demonstrated willingness to use its spending power in this unprecedented crisis to step in on commercial evictions, but they should act on residential evictions as well," writes Leon.

"Tenants that have fallen behind on rent need access to financial support in order to prevent evictions. Without such measures, we can expect more tenants to lose their homes, experience increased hardship and poorer health – all in the communities already hardest hit by the pandemic."

Hector Vasquez

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments