The history of the HMV store at 333 Yonge Street in Toronto

Thirty years ago, a major music retail battle was brewing on lower Yonge Street.

Music magnate HMV – derived from the old RCA Victor Motto “His Master’s Voice” - was planning the final stages of a new flagship store in Toronto, after soft-landing in Canada in 1988 with 47 smaller locations across the country.

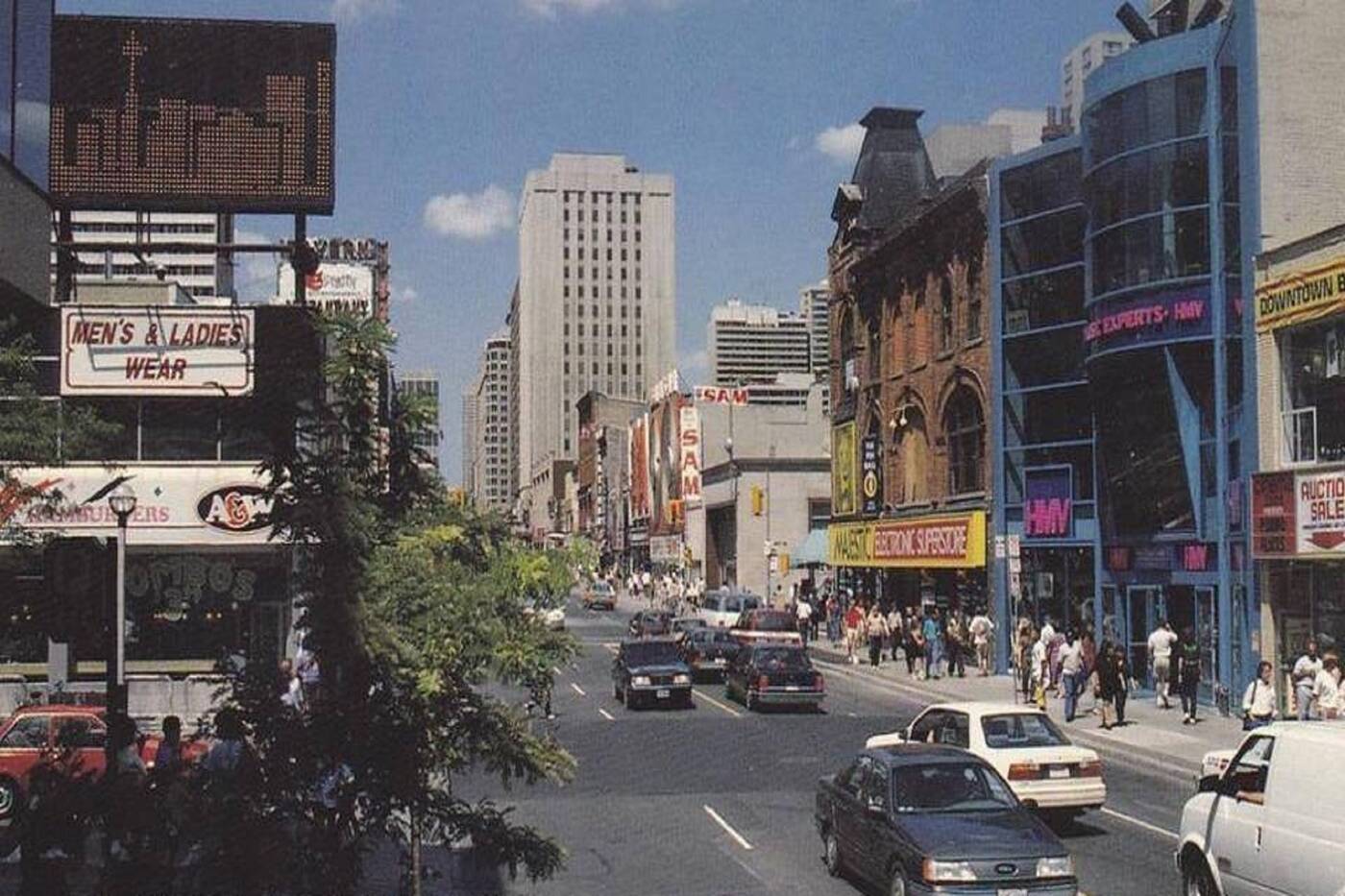

The HMV Superstore at 333 Yonge Street in the summer of 1991. Photo courtesy of Retrontario.

The sound of Yonge street

HMV had explored opening this musical palace on Bloor, but ultimately decided on Yonge Street.

Then-HMV Canada president Paul Alofs told the Toronto Star: "If you’re going to be in record retailing in Canada, you have to be on Yonge Street… serious music lovers inevitably come to Yonge."

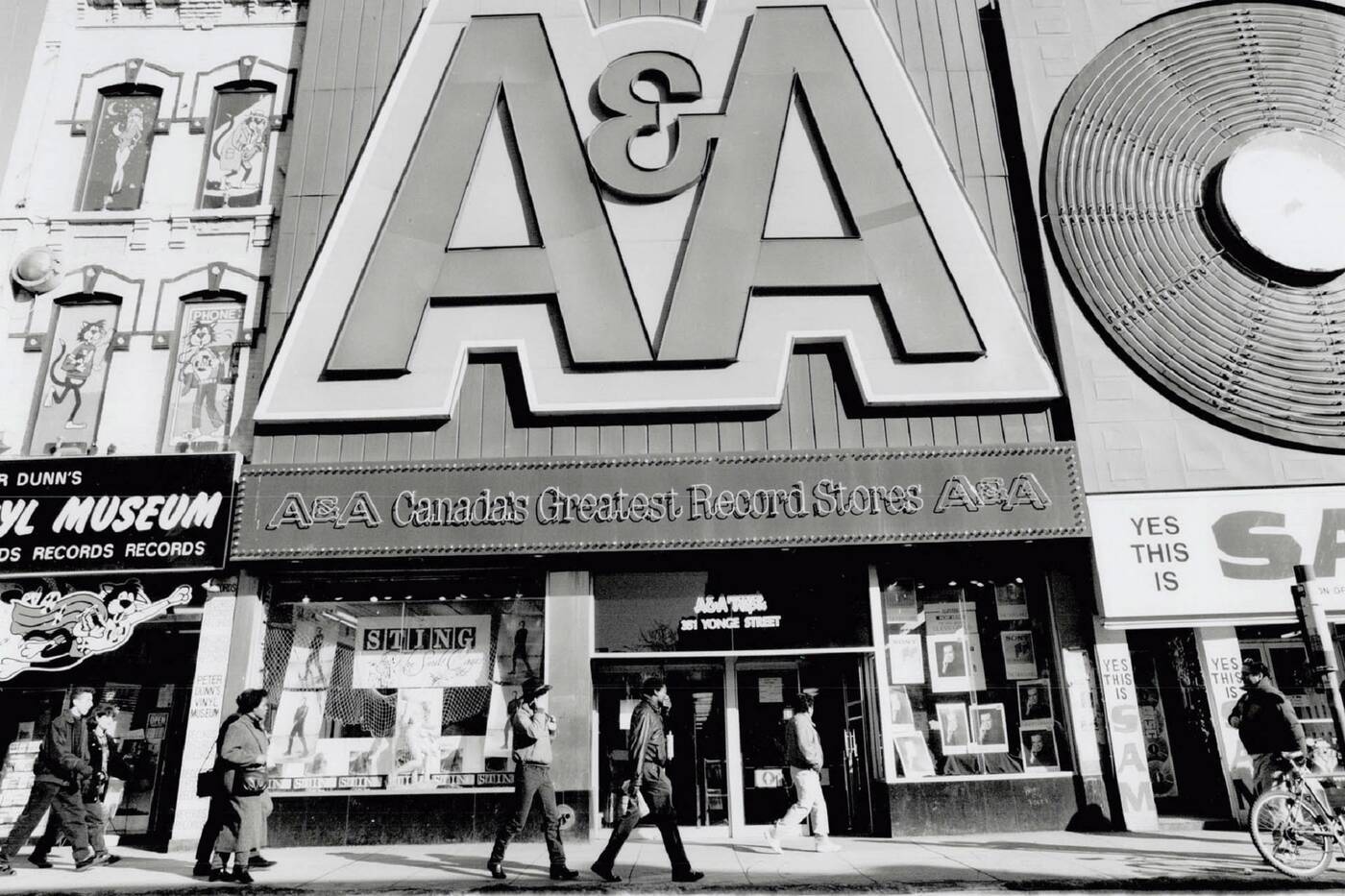

Sam the Record Man was the Yonge street O.G since 1959, followed by neighborly competitor A&A Records (both Sam and A&A had franchised locations across Ontario).

Peter Dunn’s Vinyl Museum was on the other side of A&A, while Sunrise Records stealthily competed across the street.

Rock'N'Roll duty: a row of quality music stores. Photo courtesy of the Toronto Star.

The soul of Yonge street

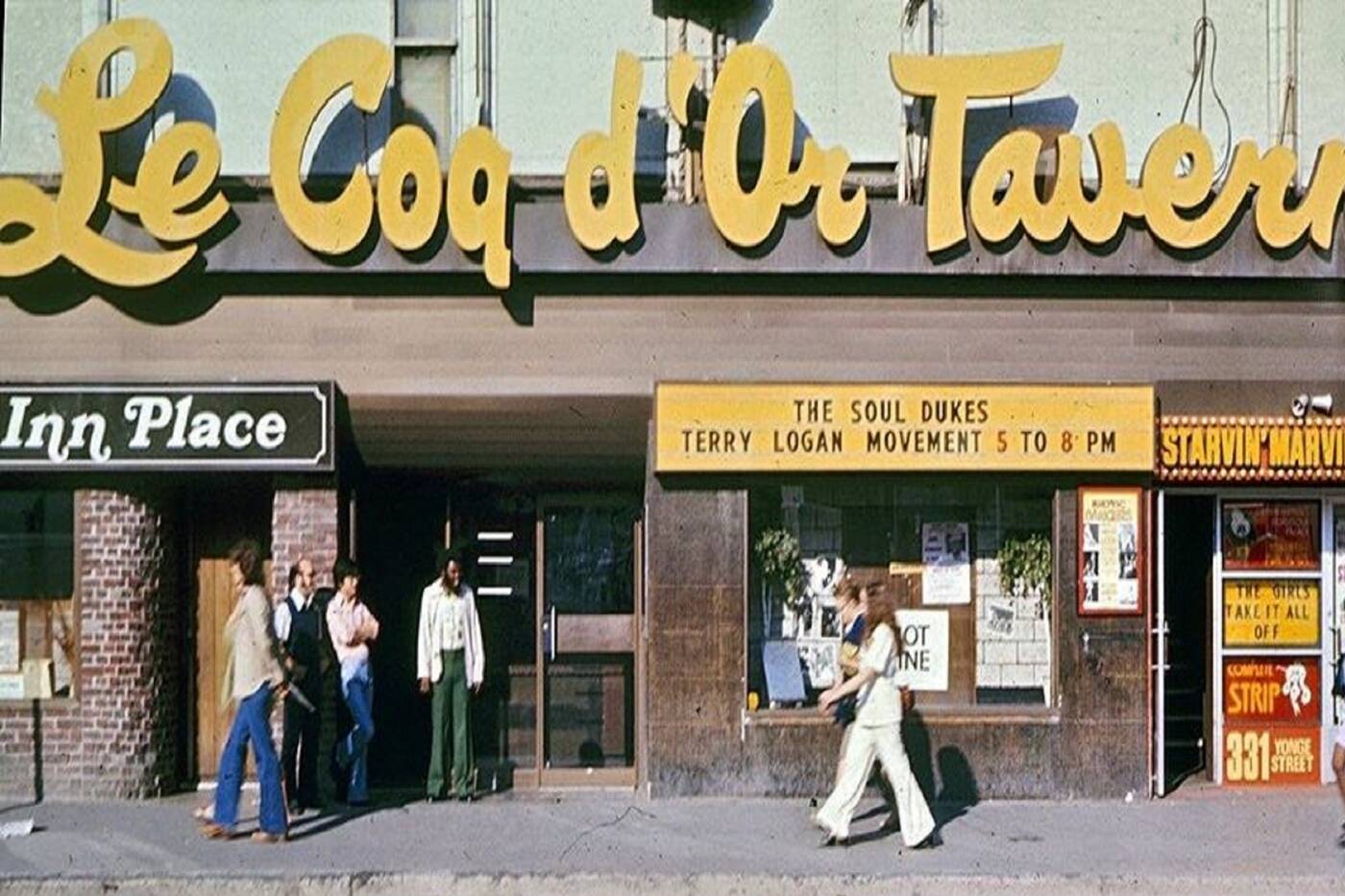

The location of 333 Yonge was chosen to be HMV’s flagship, an address already steeped in vital local music lore: It was at 333 where Le Coq d’Or Tavern offered up the likes of Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins, Bo Diddly, Jackie Shane, Solomon Burke, Sam & Dave, and many more.

Attached to the Tavern was Starvin' Marvin's Burlesque strip club, MC’d back in the day by Rummy Bishop. Good vibrations all around, one could even say.

Super soul on Yonge street. It all started at 333. Photo courtesy of Doug MacBean.

While the structure was under construction, local artist Runt (Lee’s Palace, RapCity) was commissioned to paint a mural out front.

It perfectly summed up the buzz at the time - Toronto was about to get another massive jolt of accessible music culture. It was the best of times!

Sam the Record Man

At the start of the ‘90s, Sam’s was still a goldmine of old records, CDs and tapes, but it was often disorganized and required a lot of digging (though many people actually enjoyed this).

Plus, it was expensive; if you were into, say, rare Jazz, Latin exotica or House music from the UK, prohibitively so.

In 1991, CDs cost $17.99 at Sam the Record Man. A US import would run you $20-30 and if you wanted something from Europe It was usually north of $30.

HMV blew that door off with a $14.99 offering for new CDs from R.E.M, Boyz II Men, The Tragically Hip, Indigo Girls and Tea Party.

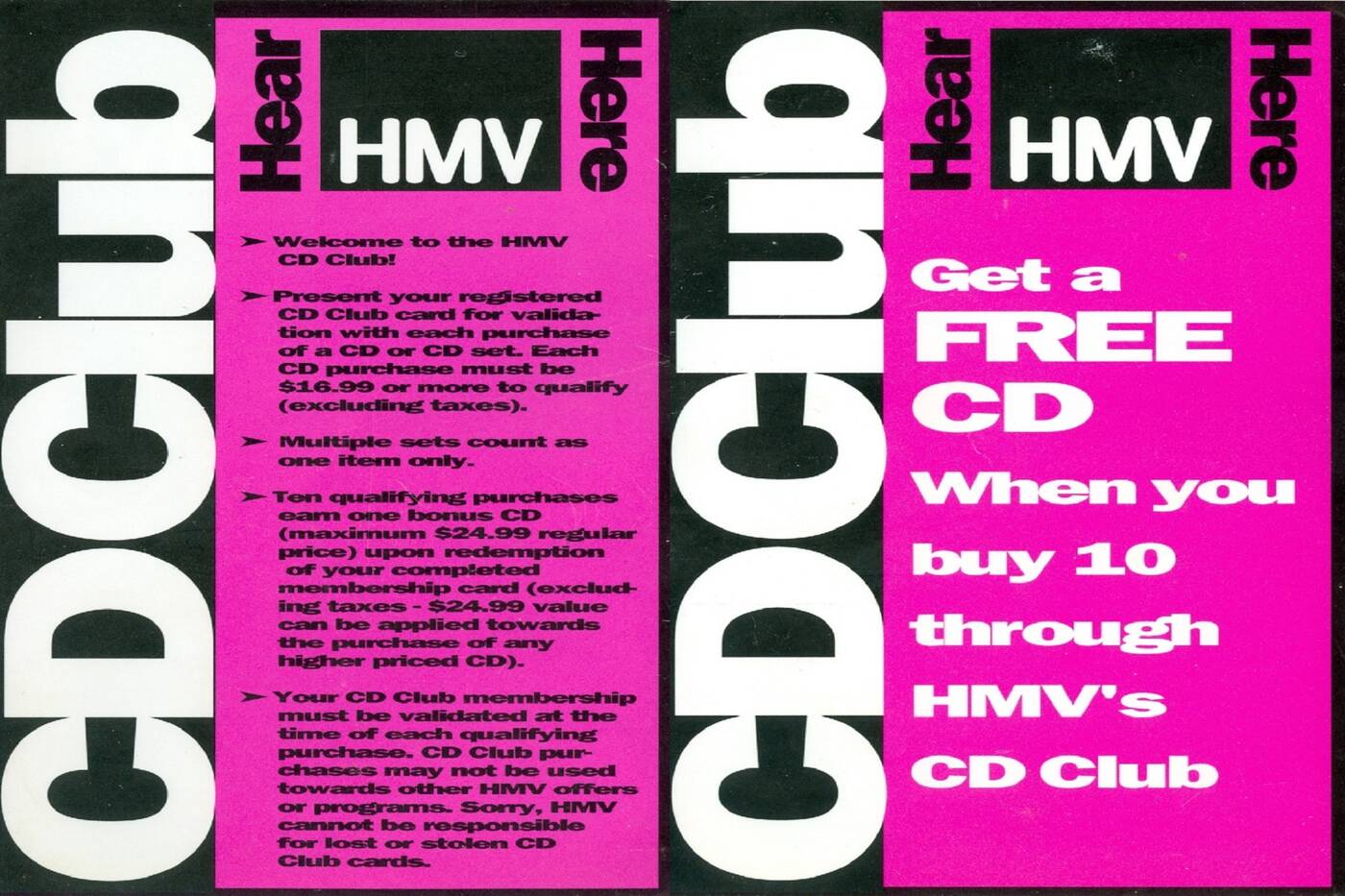

This price point was unheard of at the time, and in addition they introduced loyalty cards of the buy 10 get one free variety (for $100 ballpark Laserdiscs, too!).

Deal of the last century: Buy 10 CDs, get 1 free. Photo courtesy of Retrontario.

A music fan's dream

HMV’s gambit was that Toronto needed a meticulously organized music superstore, that not only sold CDs, cassettes, VHS, and Laserdiscs, but also celebrated them.

The store was mostly run by fans who were not viewed as “sell-outs” (that would come later), but closer to characters in High Fidelity than Empire Records.

Part of the storefront incorporated a wall of 36 monitors that broadcast loops of videos, concerts and commercials. In 1992, nervous locals gathered to watch the Blue Jays win the World Series.

Within the store there was major innovation in the form of over 100 listening posts, which eventually evolved into a huge portion of the second floor.

While listening to records in-store had been a standard since the dawn of selling music, the practice had mostly disappeared by the 90s and left many buyers stuck with $20 CDs they didn’t actually enjoy.

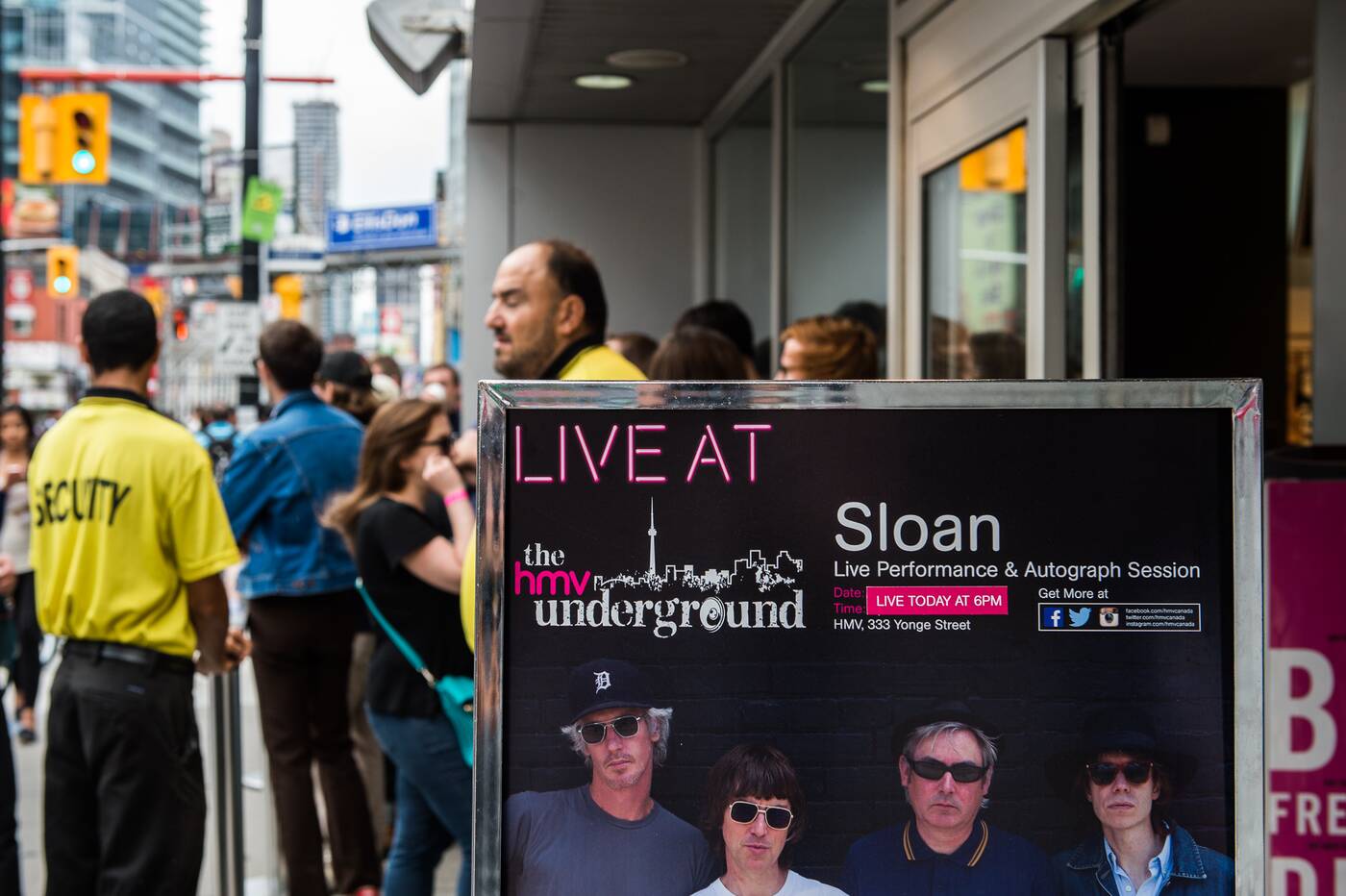

Sloan was one of many bands to perform in the underground space. Photo by Matt Forsythe.

Live in-store performance was another major selling point, with various locations set aside throughout to accommodate everything from classical pianists on the third floor to jungle DJs in the basement (later, the BASSment).

Over the years, some of those live shows attained legendary status, such as Alice Cooper performing on the roof, Green Day in the alley and Red Hot Chilli Peppers at the then ungentrified Yonge and Dundas square (keep an eye on the always amazing The Flyer Vault for sweet throwbacks to many of these shows).

In the early 2000s, a co-venture with MuchMusic saw the instillation of a mini-Speakers Corner unit called the “Much Web Cam” which allowed visitors to sound off in-store about what was on their minds:

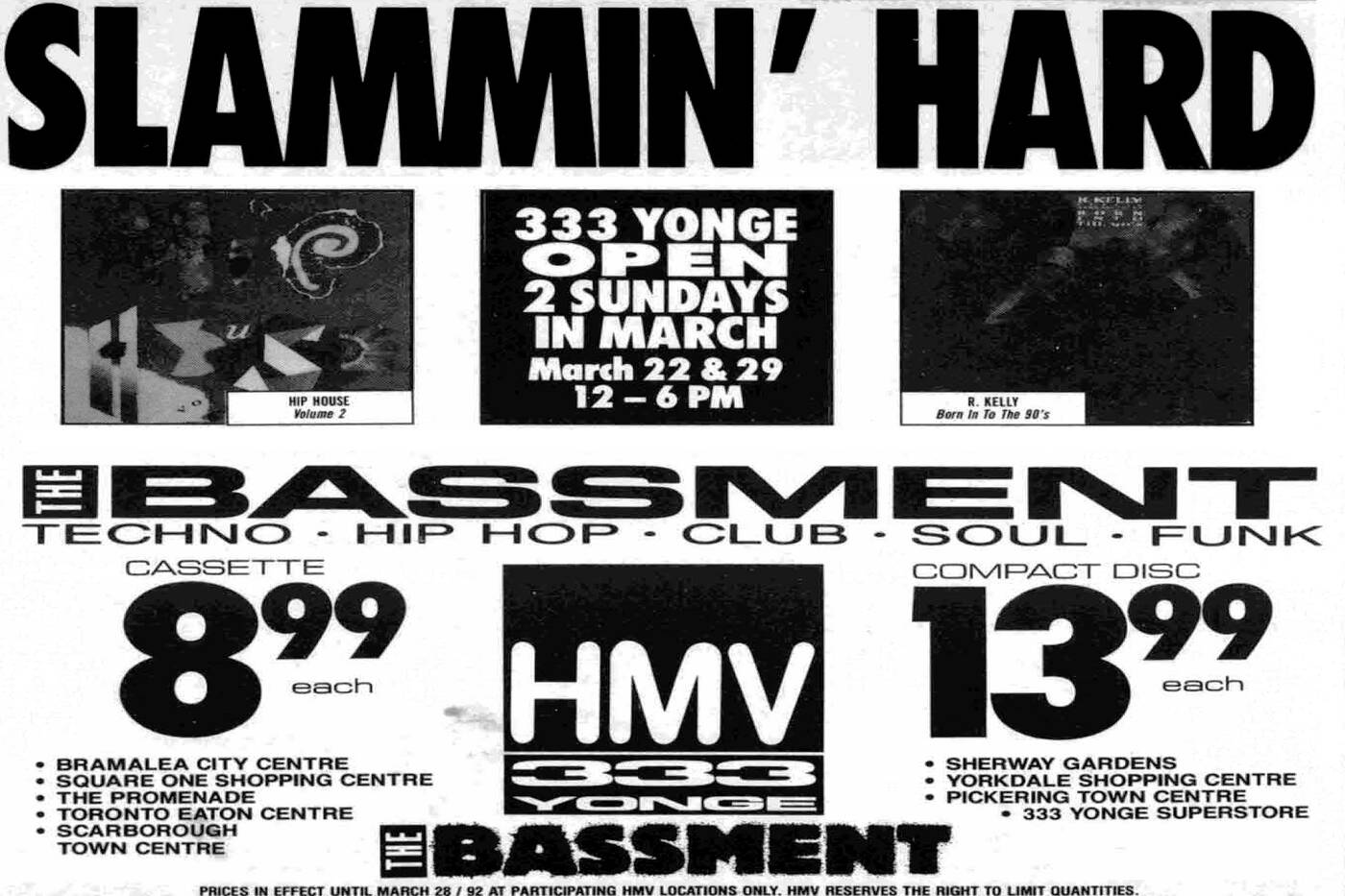

The BASSment

If you were at all into hip-hop, rap, dance or electronic music, the Bassment was a crucial drop zone.

Sure, DJs shopped at Traxx and Play de Record for vinyl of course, but if you were a collector the selection was overwhelming.

Thanks to the UK connection, HMV was bringing over more underground titles on CD quicker than anywhere else.

High in a basement - TechnoHipHopClubSoulFunk. Courtesy of The Flyer Vault.

Perhaps what is best remembered about the megastore was their ludicrously liberal returns policy.

You could return opened merchandise for exchange without receipt, which lead to a daisy chain of scamming affectionately dubbed “burn and return”.

It’s almost impossible to explain how important it felt to visit HMV back then, browsing for hours and day dreaming about all of your favourite tunes.

Before the internet it was on par with MuchMusic as the definitive destination to learn about music (and spend all your money).

Fans waiting in line to get into a concert at the underground space. Photo by Matt Forsythe.

Opening and closing

HMV threw down the gauntlet on May 3, 1991 during one of the worst recessions in Canada’s history.

Opening day featured a live performance by Chris Isaak. At the time, few believed they would even survive until the end of the year.

By the close of 1991, A&A Records was gone. Sam held out until 2007.

When HMV announced it was closing the flagship store at 333 Yonge in early 2017, no one was surprised.

Music file sharing, and later streaming, had gutted the industry, which was pegged at $750 million annual business when HMV first opened the store.

The changing face of the neighborhood now featured a regenerated Yonge Dundas Square full of technical razzle dazzle. The once vanguard HMV building came to be seen as an out-of-time relic.

But back in 1991 if you were a music fan, it was the most exciting place to be.

Matt Forsythe

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments