The history of Toronto's lost railway system

A year before becoming mayor of Toronto, Horatio Hocken stood before the city's Board of Trade to urge support for a subway beneath Bay Street.

"Toronto is notorious for postponing necessary improvements until the cost has doubled or tripled," he warned. That was in 1911. Habits form early.

Hocken's analysis wasn't entirely fair, though; the city was once ahead of the curve when it came to planning and building infrastructure.

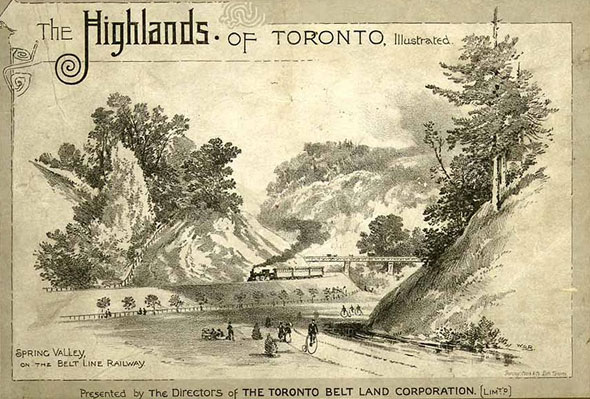

An early postcard of the Belt Line Railway.

In the late 1880s, two decades before Hocken proposed his Bay St. "tube," a group of prominent land speculators had their eyes on undeveloped rural properties north of Eglinton Ave. and west of High Park.

As long as the city continued to expand, they thought, there was money to be made establishing new suburban residential communities with convenient transportation links to the centre of the city.

It was a tried and tested model. Streetcars helped spur development in Riverdale, Leslieville, the Beaches, New Toronto, and Mimico in Toronto and neighbourhoods in other cities across North America.

To that end, the Toronto Belt Land Company was founded in 1889 by businessmen Edward Osler, William Hendry, and Sir James Edgar with John T. Moore as manager.

The company planned to subdivide and sell lots in Moore Park, Forest Hill, Fairbank, Fairbank Junction, and Swansea as well as providing a rail link to Union Station via two new lines.

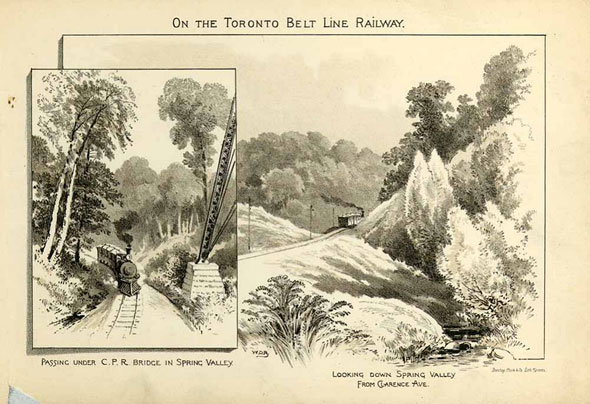

Illustrations of the Toronto Belt Line Railway.

The main 26.5 kilometre loop ran east along the main waterfront corridor, up west side of the Don Valley and Moore Park ravine (then called Spring Valley,) through Mt. Pleasant Cemetery and over Yonge.

From there it continued northwest to Bathurst, due west to Caledonia Road, and south back to the waterfront using existing GTR track.

The Humber loop, which was about 3.2 kilometres shorter than the main Belt Line, ran west from Union Station to the former Carlton station near St. Clair and Weston.

From there, it peeled west on an alignment now occupied by a hydro corridor to Jane and turned south via the Humber River valley to the GTR line at the Humber Bay and back to Union Station.

Unfortunately for Belt Line Company and its investors, the business failed several months before the lines were completed and the work had to be finished by the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) at a total cost of $462,000.

With the original operator out of the picture, GTR also took on responsibility for the service.

The first revenue train left old Union Station at 2:40 p.m. on June 30, 1892. "Each train was filled with hundreds availing themselves of the opportunity to inspect the much talked of route," the Globe reported.

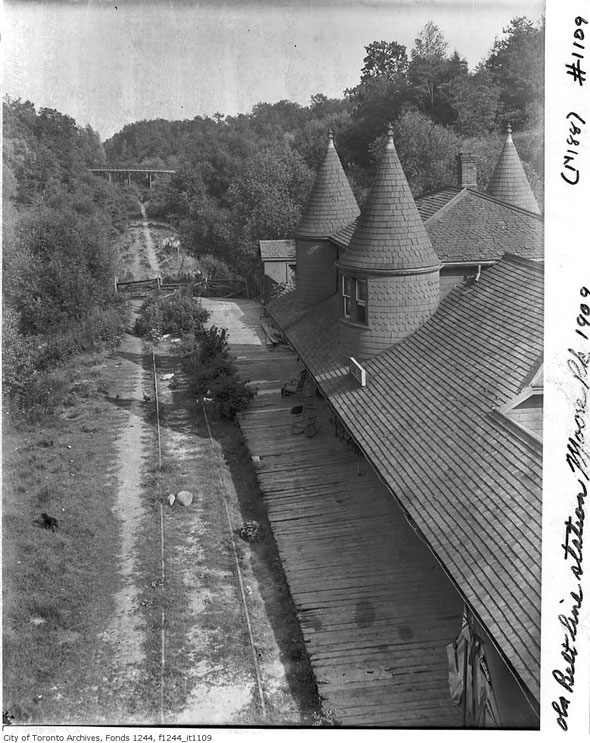

The old Belt Line Station in Moore Park.

The locomotive, built in Montreal at the Grand Trunk shops, pulled three steam-heated passengers cars, one of which was designated as a smoking and baggage car.

The seats were laid out in an "uncommon" arrangement and were made of cane and light polished wood.

A row of "quartette" seats were set up in the middle of the coach, the paper reported. "At either end are comfortable chair-like seats along both sides of the aisle. The ventilation is complete and these cars are perhaps the prettiest and brightest to be found on any [rail] road running into the city."

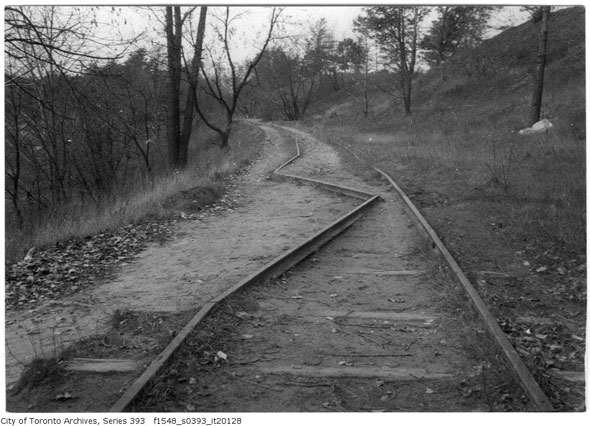

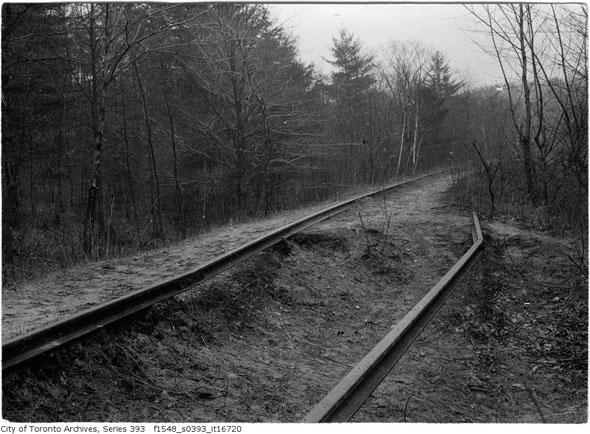

Old railway track in Toronto.

The fare was between 8 and 25 cents (about $5 today,) depending on how far a passenger intended to travel. Initially there were six trains a day delivering workers to the city and taking day-trippers on leisurely excursions.

"The new lines opening up as they do many miles of new territory high and healthy, abounding in exquisite scenery and rich in fertility, will doubtless give a great impetus to suburban home-making, while many new fields and pastures green will open up to the picknicker and Saturday afternoon holiday keeper," the Globe enthused.

Railway tracks running through the Belt Line.

Despite the promising concept, many passengers turned their noses up at the steep ticket prices. The anticipated land boom did not materialize due a severe economic depression.

Less than two years after its launch, GTR abandoned the service and repurposed parts of the line for other operations.

The old Belt Line tracks.

Track still lingered in abandoned parts of both loops until the first world war when it was taken up and shipped to France. Moore Park station with its grand spires was converted into a home and likewise razed around the same time.

Today, much of the old Belt Line route forms part of the Kay Gardner Beltline Trail. Informative plaques mark the location of many of the old stations and new platforms are being built where the old train stations used to be.

Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments