A brief history of a secretive Toronto millionaire

The enigmatic William Cawthra cuts a mysterious figure. By far the richest man in early Toronto, he spent relatively little of his money, kept few close friends or personal records, and left no will or children, yet his legacy is an important one.

His lost mansion at King and Bay―one of his few indulgences―and the home his wife built on Jarvis Street after his death were conspicuous parts of the city's early streetscape. As a result, there are numerous landmarks that bear the Cawthra name.

Last month, Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam backed renaming the newly renovated Cawthra Square Park, the Church Street green space that houses the Toronto AIDS Memorial, after former mayor Barbara Hall. A lawyer in the 1980s, Hall represented members of Toronto's gay community arrested in the 1981 bathhouse raids. As the city's last pre-amalgamation mayor, she became the first head of council to march in the Pride parade.

"Barbara in many ways led the way for the LGBT community as a very quiet ally, but a very important one," says Wong-Tam. "She stood up for the community at a time when very, very few allies would, especially those who were not LGBT. So for the community to acknowledge someone like Barbara, who has a very deep emotional and spiritual connection to the community, I think is very befitting."

As the city prepares to make the change, a little about the man for whom the park is currently named.

William Cawthra was born to Quaker parents in Yorkshire, England in 1801. His father, Joseph Cawthra, came to Canada in 1803 (possibly 1806,) first settling near the Credit River. In Toronto, he opened a combined apothecary and general store that sold a dizzying array of products, many of them imported from America: Whitechapel needles, forks, scissors, cognac, shoes, and hats, in addition medicinal treatments.

The store was a success―medical supplies were desperately needed by the British Army during the War of 1812―and Joseph invested the profits in an array of local property. William worked in the store and later inherited the business when his father died in 1842.

Rather than continue selling drugs and sundries, William closed down the store, content to collect an ever increasing amount rent from the family land in the heart of Toronto.

Despite a shy and retiring character, Cawthra represented St. Lawrence Ward on Toronto's first city council in 1834, and again in 1836, though it appears he was never comfortable in the spotlight. As historian Stephen Otto notes in a 1981 biography of Cawthra, a stint as a school trustee and commissioner of the provincial lunatic asylum allowed him to serve the public from afar.

Though he didn't invest his fortune in any great public institutions (he briefly considered establishing a public library,) he gave generously to the House of Industry on Elm Street, the Toronto General Hospital, and the Newsboys' Home, a charity that sheltered homeless young men and put them to work delivering newspapers.

In 1849, William Cawthra married Sarah Ellen Crowther, who was 17 years his junior and the sister of a prominent local lawyer. "She was a woman of some assurance and decisiveness, perhaps in matters where her husband was less interested," Otto writes, and it's likely she was the driving force behind Cawthra's only monument, his mansion at the northeast corner of King and Bay.

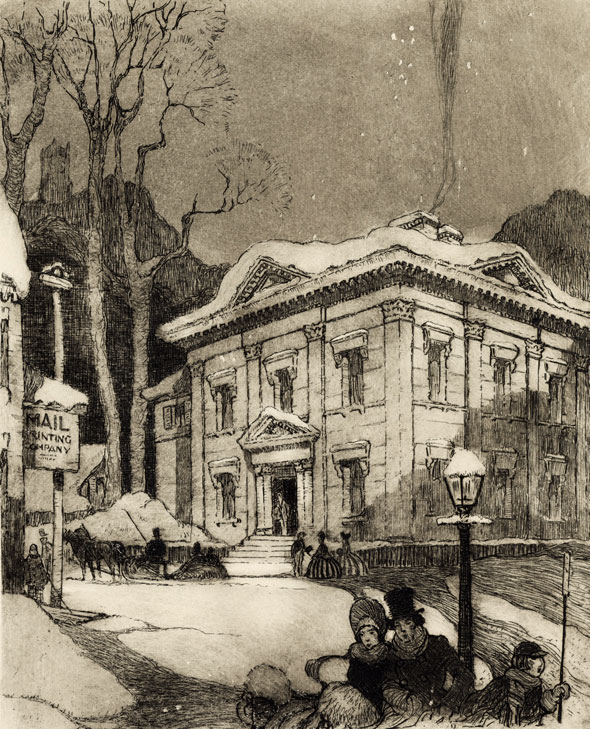

Designed by young architect Joseph Sheard, a carpenter by trade who Cawthra may have come to know through his work on the House of Industry, the two-storey, off-white Greek Revival building featured an ornate exterior of sculpted Ohio sandstone at a time when much of the city was made of wood or brick.

Intricate corinthian columns and detailed pediments above the windows and doors led respected architect John Howard (he that gave the city High Park) "one of the best designed buildings in Toronto."

"There it is. That's Joseph Sheard's work, and good work it is," he told a writer for the Toronto Telegram as they examined it from a nearby window in 1888.

Like Cawthra himself, we really only know the home from the outside. No detailed descriptions of the interior have survived, but the tales it spawned live on. It's rumoured Cawthra's butler removed the solid gold exterior door knobs and replaced them with ones made of brass each night.

At the time of Cawthra's death, three days after undergoing surgery in 1880, the family estate was valued at $2.4 million, roughly a billion dollars in today's money, much of it accumulated through interest. Curiously for a man of great wealth, Cawthra died without leaving a will (perhaps he expected to live longer) and he and his wife did not have any children.

A judge decided the money should be split equally between his widow, his two nephews and niece, in doing so launching one of the great moneyed families of early Toronto. A book that recalls the family history of the Cawthras describes William's heirs as the "'Astors' of Upper Canada" for their lavish lifestyle.

Crowther used her portion of the estate to build a new home on Jarvis St., opposite where the park that bears her husband's family name.

The King Street mansion, the city's best link to the mysterious Cawthra, was turned into a bank branch, which is apt considering owner of the great fortune it used to shelter: first Molsons Bank, then Sterling Bank, and later offices for the Bank of Nova Scotia. It was knocked down in 1946 to make way for the latter's new headquarters.

Before the house was pounded into dust, Anthony Adamson, a descendent of the Cawthra family, had several of the columns and exterior sandstone fixtures moved to his Rosedale backyard. They remain there to this day, covered in a thin layer of moss.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Image: "Mr. William Cawthra," Benoni Irwin, 1868; Cawthra house etching, Stanley Francis Turner, 1922, Toronto Public Library, X 31-3; "Cawthra, William, house, Bay St., n.e. cor. King St," 1897?, Toronto Public Library, E 10-73; "Northeast corner of King and Bay streets," ca. 1926, City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 7098.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments