A brief history of the Canada Life weather beacon

There are countless ways of finding out whether tomorrow will be an umbrella day in downtown Toronto, but the method that will most impress your friends involves decoding a secret signal from the roof of a historic downtown building.

The weather beacon on top of the Canada Life building at Queen and University, the oldest device of its kind in the country, has been flashing out tomorrow's weather for 62 years this month, through hurricanes, ice storms, and lightning, and tempest, using the same easy-to-read system of lights.

"The Thing," as it was affectionately known by Canada Life management, is well worth getting to know.

University Avenue in its original form was a short, broad and largely undeveloped stretch of road from Queen Street to College Street. Before graduating, the street was called College Avenue, and provided the bizarre - now lost - intersection of College and College, just south of Queen's Park.

It's tough to picture now, but Toronto had to grow in order to fully absorb it's grand tree-lined street. Early maps and photographs show it as a relatively lonely semi-rural road with dense overhanging trees and a lush green median in the years around 1900. The view south from Queen's Park could easily have been mistaken for the verdant entrance to a forest or a secluded copse.

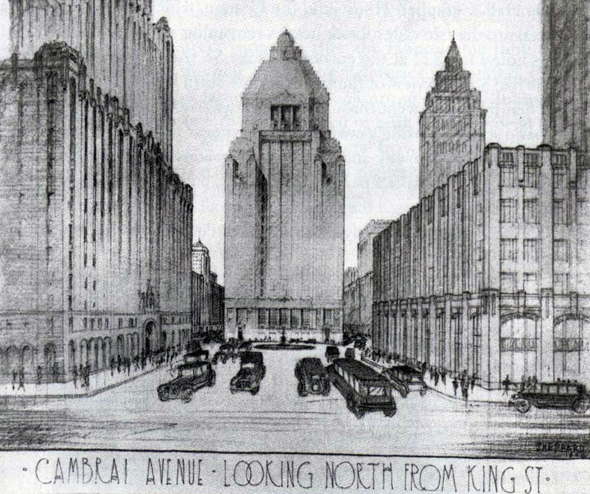

Fast forward to the 20s, and the city had big plans for its principle boulevard. The road would be lined with grand and arresting beaux-arts and art-deco buildings and extended south from Queen to Front Street and the new eminence of Union Station.

The crowning glory was to be Vimy Circle, a stately round intersection like Paris' swirling Place Charles de Gaulle to be located at present-day University and Richmond. A surviving sketch from the era shows Fords, Cadillacs, and Marmons wheeling around a central monument with a neat grassy park at its base. New, unrealized buildings loom large like a scene from Gotham City.

When the Depression began to cut deep in the early 30s, the ensuing financial uncertainty severely hamstrung the city's ambitious expansion plans. Not only would Vimy Circle and the radial roads planned for the area be nixed by nervous citizens in a 1931 referendum, voters would also turn away Cambrai Avenue, a new road planned between Front and Queen just north of Union Station at the expense of the Royal York Hotel.

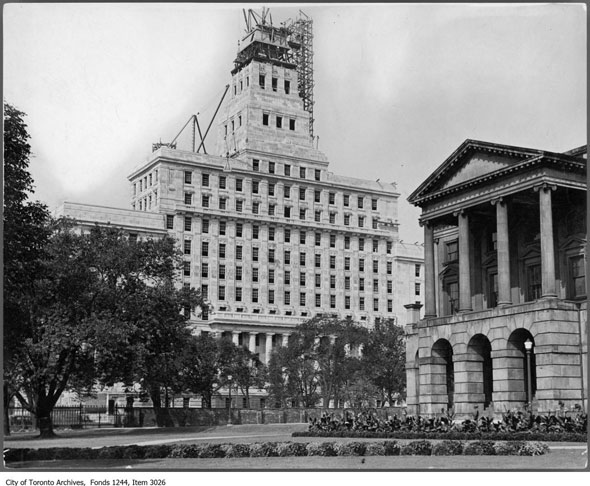

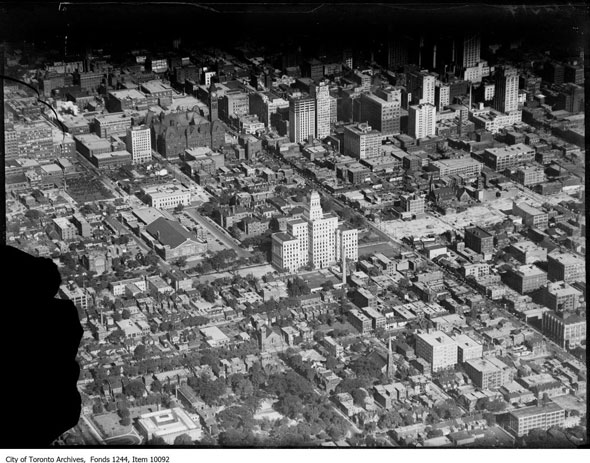

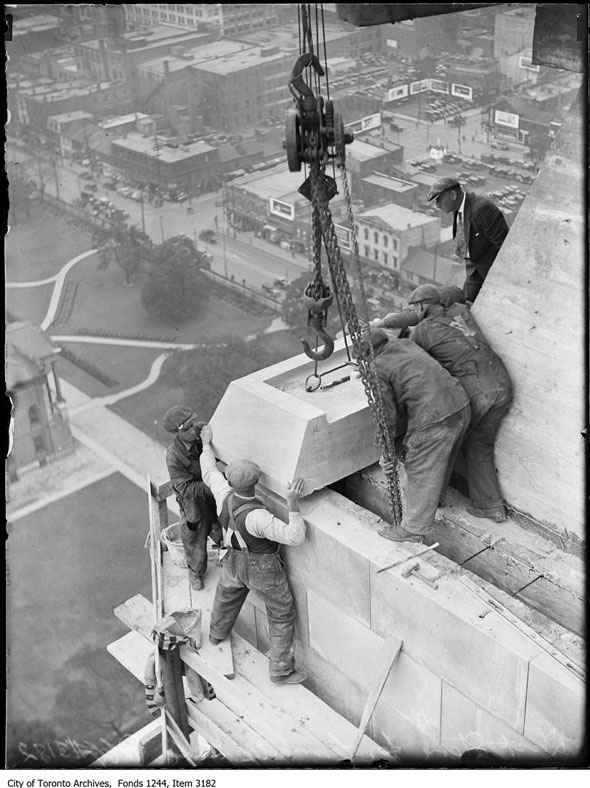

From the ashes of those civic plans rose the impressive Canada Life building, one of just a few major Toronto structures from the era to be fully realized. Rising 17 stories above the street in a sheer wall of Indiana limestone, the Sproatt and Rolph design for the headquarters of the country's first domestic life insurance company was one of the tallest in the city when it opened on March 16, 1931, even without its famous spire.

Despite the financial instability that dogged the era the building was astonishingly opulent. 10 Tuscan columns carved from Georgian granite faced the street, creamy Italian Travertine and Saint Genevieve Golden Vein marble panels covered the floors and walls beneath an ornate ceiling lined in gold leaf. An observation deck, located on top of its central tower, provided panoramic views over the city.

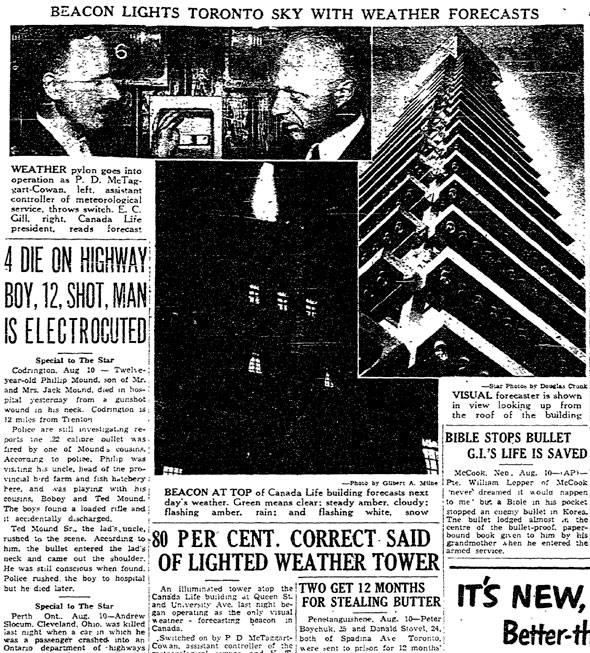

Despite its intricate details and dominating presence, the weather beacon added to the observation deck like a sparkling crown in 1951 is the feature that still draws the most eyes. "The thing," as company chairman W. J. Adams dubbed it, was 12.5 metres tall, 98 metres above the street, and cost $25,000.

1,500 individual light bulbs and 9,000 feet of wiring poured in braids down the inside of the metal frame in to a staffed control room. All those colored bulbs drew an estimated 22.1 kilowatts, roughly the same as a building-sized air conditioner would today, a significant drain on the early electrical grid.

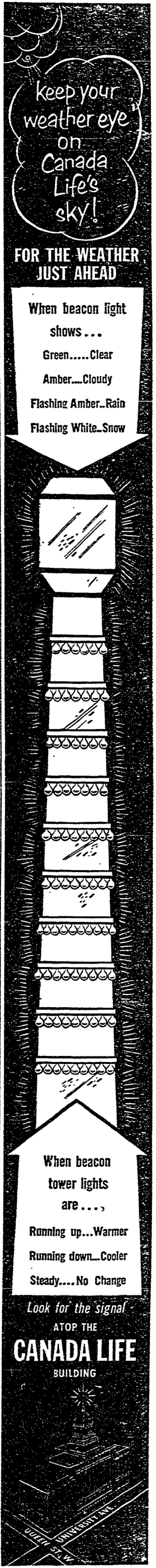

For the uninitiated, the lights of the beacon illustrate the weather forecast thusly: the yellow lights on the shaft move from bottom to top when the temperature is climbing and fall when the weather is cooling. No movement means the temperature is forecast to stay the same.

The coloured box at the top flashes red for rain and white for snow - if it's solid green the weather is clear, solid red means it's going to be grey and overcast.

The colourful display was proudly switched on for the first time on August 1951 by P. D. McTaggart-Cowan, assistant controller of the meteorological service, and K. T. McLeod, superintendent of the public weather service.

"We feel it should create a real interest besides being a useful service to the people of the city. For most people the weather provides a topic of conversation at all times," E.C. Gill, President of Canada Life told the Toronto Star in 1951. Similar pylons, on top of the Mutual Life building in New York and the John Hancock building in Boston, were popular focal points at the time.

Then, as today, calls were made to the Environment Canada Weather Centre at Pearson four times a day for tomorrow's forecast. The results - "80% correct" in 1951 - are programmed manually by way of a series of switches in the control room.

At first the illustrated weather reports were only active on between sunset and the 2 AM - the bulbs, dim by today's standards, weren't bright enough to be seen in daylight, but during the winter the lights were activated in the early morning half light.

24-hour weather predictions arrived with improvements in lighting technology but several years ago Canada Life began once again turning off the beacon at midnight, citing energy concerns and the cost of constantly replacing the 1,000 incandescent bulbs, strained to death by the bursts of electricity required to make them flash.

A month ago, the company upgraded the famous display to use energy-efficient LEDs. 19 rows of high-intensity bulbs still flash out weather predictions, a reassuringly old-fashioned medium in a time when it's just as easy to get the same information in your pocket.

MORE IMAGES:

A newspaper advert published shortly after the beacon was switched on

The frame of the Canada Life building takes shape beside the Boer War memorial

Workers lay the final stone on the Canada Life building

A boardroom in the Canada Life building

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto, Canada Life

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments