The catastrophic explosion that defined the War of 1812

On this day exactly 200 years ago one of the most powerful explosions ever witnessed in North America tore through Fort York, shattering a brief calm in the battle for control of the town of York. The blast was so powerful it rattled windows 50 kilometres across the lake in Niagara and killed men over 180 metres away.

In retaliation for the attack, the Americans would burn and loot the town, leaving its government and military structures in ruins. The magazine explosion during the Battle of York would permanently alter the tone of the battle for control of Upper Canada and still leave marks on the landscape centuries later.

On April 26, 1813 trouble was brewing for the burgeoning town of York. British forces were embroiled in the Napoleonic Wars, a 12-year series of battles for control over Europe that stretched the country's military capacity at home and left its colonies vulnerable to attack without reinforcements.

Sensing the chance to wrest control of Upper Canada, American forces mounted an invasion by water from York Harbour. As is noted in the documentary Explosion 1812, the incoming soldiers believed many of the settlers of Upper Canada - the mostly American "late loyalists" - would welcome their arrival, or at least not provide much resistance.

When the American armada of 14 ships arrived in the waters off the shore from York, the population of the town was roughly two-thirds American born. The soldiers at Fort York comprised a small official resistance of around 300 troops. An additional 300 militia men in the town and 100 Mississauga and Ojibwe soldiers were also prepared to fight for the British cause.

By contrast, the American army included 1,700 soldiers, including a notorious team of riflemen under the command of Officer Benjamin Forsyth, "a man killing idiot ... every honest man must condemn" in the words of a contemporary. Forsyth's troops wore green jackets - good camouflage - and were known for their deadly rifle skills. The defending side were outnumbered 4-1.

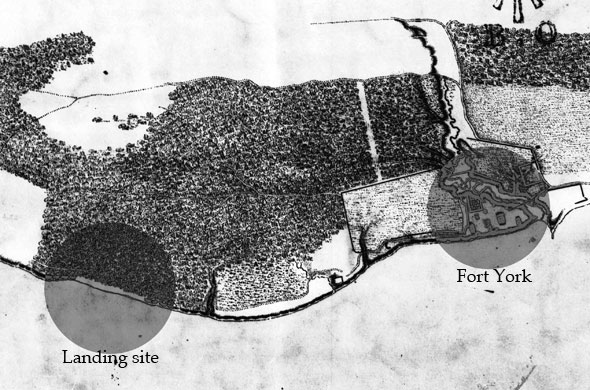

The army landed at 7:20 AM, several kilometres west of the fort - roughly west of the CNE grounds - in dense woodland where they took up position waiting for the arriving soldiers from Fort York.

The first shots were fired between Forsyth's armed soldiers and native troops lead by James Givins backed up by a handful of grenadiers from the 8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot, who were easy targets with just their bayonets and bright red jackets.

The armed militia lead by local landowner Aeneas Shaw failed to appear in support as expected. Their absence is a still a mystery, though there's a chance the group became lost or confused on their route along Queen Street toward the battle ground. In Explosion 1812 it's suggested the group may have preferred to wait out the battle at Shaw's home on today's Shaw Street.

The battle lasted around five and a half hours and ended in defeat for the defending side by around midday with heavy losses for the Royal Artillery, 8th Regiment, Royal Newfoundland Regiment, Glengarry Light Infantry, York and Durham Militia, and native soldiers. The remaining troops had fallen back east of the Don River, burning the wooden bridge behind them and abandoning the Fort.

As a parting blow, General Roger Sheaffe ordered the grand magazine, the weapons store for the fort to be torched to prevent it falling into American hands. The timber structure on the shore of Lake Ontario was packed with around 30,000 pounds of gunpowder, 30,000 cartridges, 10,000 cannonballs and numerous musket balls.

The flag was left flying to trick the invaders in to thinking the defenses were still occupied.

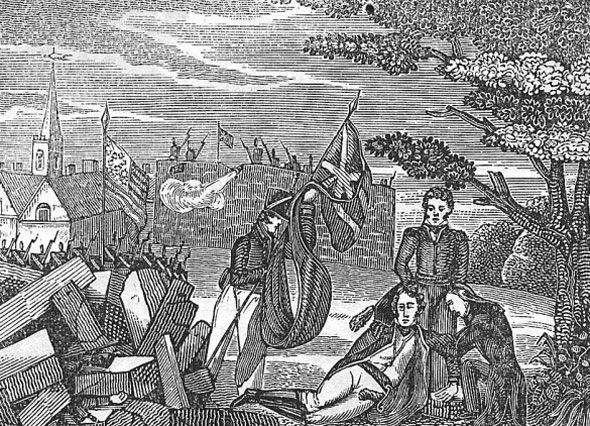

When the weapons store exploded at around 1:00 PM it let out a blinding flash followed by a thumping shockwave and maelstrom of shrapnel and debris.

The initial force traveled at 500 metres a second and was powerful enough to perforate eardrums and hemorrhage the lungs of Pike's soldiers who were massed outside the Fort waiting for the official surrender. Large rocks, twisted metal, and pieces of timber rained down for up to 30 seconds after the initial explosion.

25 people were killed - including Zebulon Pike - and 200 more were seriously wounded. The heavy damage inflicted on the invading troops was partially down to luck: the door of the magazine faced the American troops, directing the brunt of the blast their way. In contrast, some men in the abandoned government house a short step away were largely unscathed.

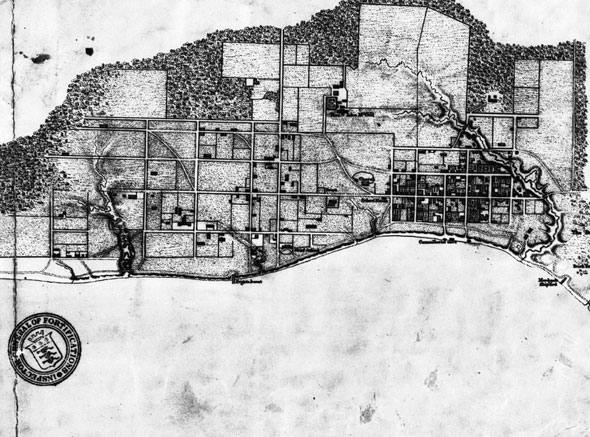

When the dust settled the remaining Americans were free to move in to the York where the remaining citizens were "standing in the street like a parcel of sheep." Over the coming weeks the town would be torched and looted. Particular attention was paid to the home of James Givins, the leader of the native troops.

Fighting beside indigenous people was considered serious misconduct in the U.S..

One of the most symbolic items looted was the King's Royal Standard - a flag flown during the visit of important royal representatives. To date the item, currently stored at the Royal Naval Academy in Anapolis, Maryland, is the only Royal Standard captured during battle that has never been recovered.

In Explosion 1812, the narrator tells the story of a Mrs. Powell who returned to find her house being looted. When questioned, the solider identified himself as being born on the farm her father owned in the northeast United States. The incident underscored how many of the Americans and new Canadians were from the same stock.

Among the other buildings lost in the raid included the town's printing press and Legislative Assembly building located on Front Street between today's Berkeley and Parliament streets (hence the name of the latter.)

The Americans would eventually retreat of their own volition to take up positions closer to Niagara and continue to battle for control of the area. Victory for Britian in the Napoleonic Wars in 1814 turned the tide of war back in favour of the Redcoats - 4,000 re-mustered troops would later invade Washington, D.C. and torch the White House in revenge for the burning of York.

Back in Toronto, the site of the magazine was located by excavation teams west of Bathurst Street and just north of the Gardiner Expressway. The gigantic crater, marked on the lead image with a "D," was filled in with debris from the fire damaged buildings and built into the ramparts of the new fort.

Twisted metal was found 200 metres away in the Garrison's parking lot.

While it's difficult to easily estimate the precise power of the grand magazine explosion, it was easily one of the most powerful blasts in North America until the Halifax Explosion more than 100 years later.

To commemorate the Battle of York, Prince Philip is visiting Toronto this weekend to present a new ceremonial flag to the Royal Canadian Regiment's 3rd Battalion. There'll be a number of events running all day, including a parade through the city of more 1,500 sailors and soldiers and a parachute display. Head out and commemorate a key moment in the creation of our city.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Image: "1816 Nicolls & Duberger Plan of the Fort at York Upper Canada;" "Part of York, Upper Canada" by Elizabeth Frances Hale, 1804; "Sketch of the ground in advance of and including York, Upper Canada" by Geo. Williams, 1813;" "York Barracks, Lake Ontario, May 13 1804" Lieut. Sempronius Stretton, 1804; "The death of U.S. General Pike at the battle of York, 27 April 1813," engraving;

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments