Why can't cities get a fair shake in federal elections?

Conspicuously absent from the campaign rhetoric of the major parties during the lead up to the 2011 federal election has been meaningful discussion of cities and the needs of urban voters. Sure there's been mention of urban transportation woes and infrastructure projects, but to watch the leaders debates, you wouldn't get the sense that more than half of Canada's population resides in metropolitan areas.

The under-representation of cities in federal politics â both in terms of campaign promises and the relative influence they're afforded within the electoral system â might be old news to the average urbanite, but a new report from the Martin Prosperity Institute (PDF), aptly titled "Who Cares About 15 Million Urban Voters?" highlights just how problematic this situation has become.

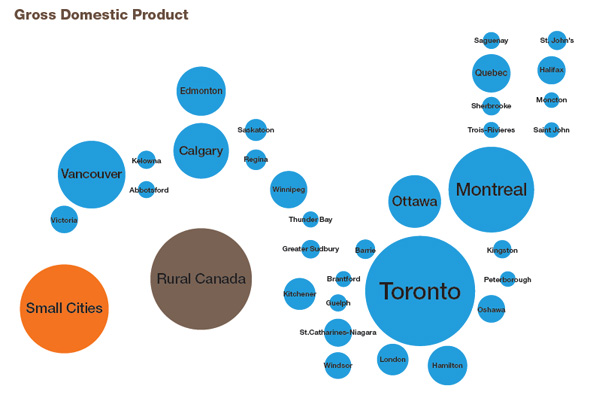

Take just the big-money statistics, for instance. Residents of metropolitan areas account for $17.5 billion in personal income, $910 billion in GDP, over 74% of all new jobs created in the past year, and are home to 67% of eligible voters. In fact, even when the suburbs are removed from the equation, core urban areas make up 40% of the population, GDP, income, and eligible voters.

Given that Toronto is the biggest of the bunch as far as Canadian cities go, the report outlines a number of steps the federal government could take to better accommodate our urban centres. Chief among them is the mere recognition of the important role that these areas play to the health of the country. "It is not just a question of more spending and greater funding for infrastructure," the report states. "Although important, our cities more urgently need some attention and recognition of their significance. Unless we recognize the value generated by our urban areas and actively work to amplify that value, we will be committing ourselves to slower growth and reduced prosperity for all."

Also on the list is immigrant settlement assistance (urban centres are home to 90% of the country's immigrants), a renewed commitment to affordable housing, the establishment of a research arm tasked with monitoring changes in cities (and with suggesting where investments should be made), and concrete policies that would help Canada's major cities to remain competitive in the global economy.

All of this makes sense, but the next step is figuring out how to actualize some of these recommendations. The most obvious option is also the least likely. If the federal electoral system could ever be converted to proportional representation, you can bet that politicians would be scrambling to meet much of what's outlined above and in the report proper. But given that this isn't (at all) likely to happen, the challenge to get more for cities is very much left to municipal leaders, who are forced to demand a fairer shake from the federal government.

It's curious, then, that Toronto's have been dead silent.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments