Nostalgia Tripping: Social Housing in Toronto

Based on my conversations with friends and co-workers, government-subsidized housing is a contentious subject among many Torontonians. On the one hand, there is the belief that this program is out of hand - already the largest state-sponsored housing project in North America, which is an outdated urban renewal model that falls easy prey to abuses and contributes to the "ghettoization" of urban and suburban neighbourhoods. On the other, the argument follows that there are not enough social services in the city and that providing a roof over the head of a socially and economically disadvantaged individual is hardly an end to his or her struggles - illustrated many times over in the columns of the Toronto Star's Joe Fiorito. Nonetheless, few would agree with the complete dismantling of public housing.

Historically, what was the founding principle upon which the ideal of social housing is based in Toronto? Obviously, as a multicultural metropolis, the city today faces much more challenging and complex social problem than in the nineteenth century as a mostly industrial, homogeneous city. At the same time, it is worth looking back at the origin of housing projects in Toronto in order to explore the necessity that first warranted the construction of city's first affordable housing dwellings.

Public housing is mostly associated with the postwar philosophy of urban renewal, which resulted in the block busting of entire inner-city neighbourhoods, such as Cabbagetown and Moss Park to make way for drab, uniform buildings. Within two decades, the quick deterioration of Regent Park proved that this philosophy in urban planning was a failure.

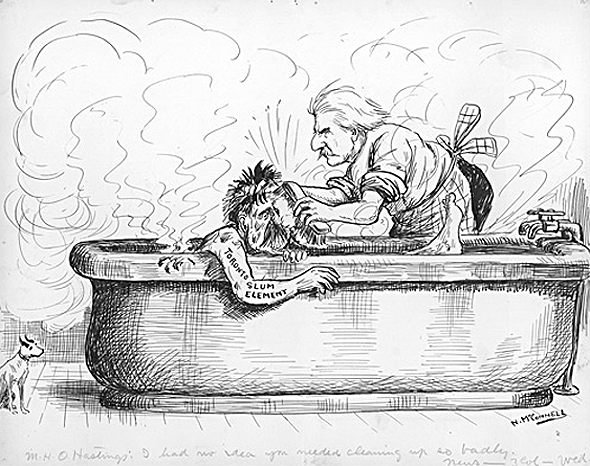

According to John Sewell's The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning, Dr. Charles Hastings (1858-1931), the city's medical officer of health between 1911 and 1930, was influential in the housing reform in the early years of the second decade of the twentieth century. He asserted that good housing was vital to his broadly defined concept of public health, of which he was a pioneer.

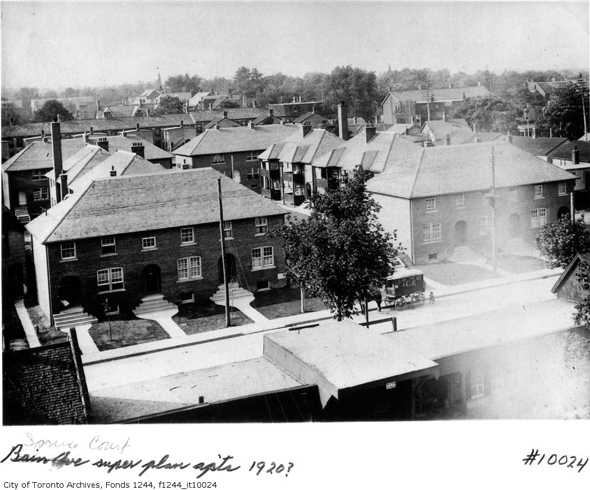

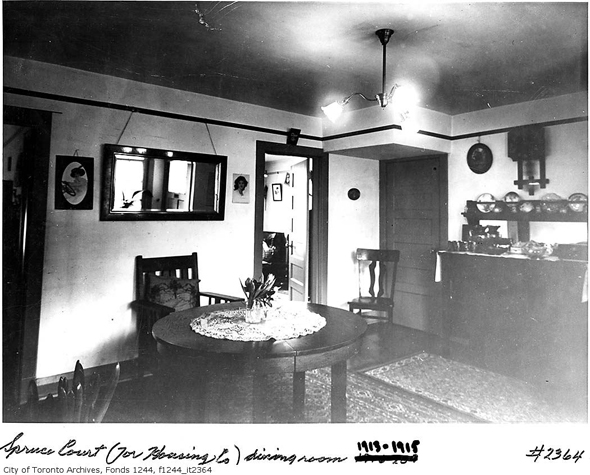

The first public housing project was Spruce Court Apartments in Cabbagetown/Don Vale, built in 1913 with a second section constructed a decade later. They are located at the corner of Sumach and Spruce Streets, still standing today and now operating as resident-owned co-operative housing. The units were designed by A.S. Mathers, and the style was directly influenced by Letchworth Garden City in Great Britain. It is characterized by courtyards, fake half-timber decoration and large slopping roofs.

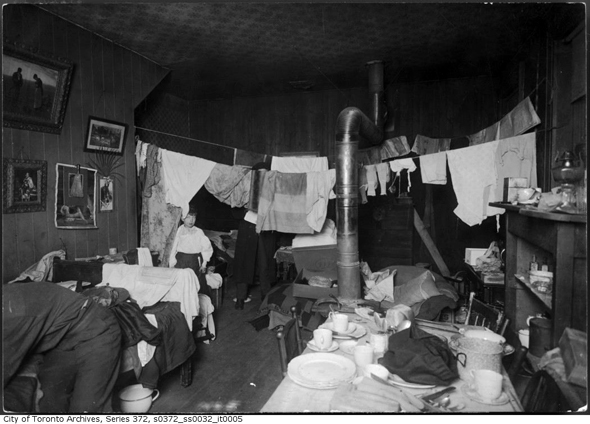

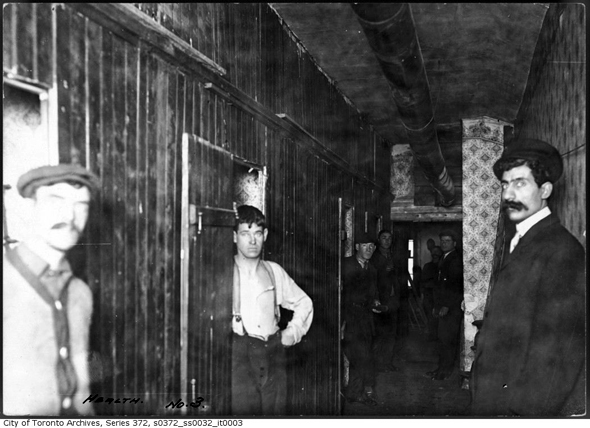

Lawrence Solomon, in Toronto Sprawls: A History, writes that Spruce Court was constructed to remedy the deplorable housing conditions of the Ward, a working-class and immigrant neighbourhood consisting of a series of slums. The new houses, built by the Toronto Housing Commission, were solid, well-ventilated and bright, with pleasant detailing throughout. Each "cottage flat" (or what is now called a duplex), had separate entrances, gas stoves and electric fixtures.

The monthly rates varied from $14.50 per month for one-bedroom apartment to four-bedroom, two-storey units for $29. However, in spite of subsidies provided to the tenants, many working-class families of limited means were not able to meet the terms of rental agreements. Landlords demanded their payments in advance, and large families were barred from living in the smaller units. Repeated increases in the rates of rent sometimes amounted to half the monthly earnings of the tenants.

Eventually, the worker tenants were driven out, not being able to afford the rent. And even though the THC periodically increased the rates, they were not able to make a profit from the rentals, which led to the closing of the project in the mid-1930s at the height of the Great Depression. Aside from the fact that the project represented a minuscule percentage of all the housing in the city, it failed to make a lasting social contribution that would have improved the lives of the workers in the inner city.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments