CONTACT Report: Questioning Conventionality

In my last post I mentioned that I was a bit tight on time when I took in my first round of shows at this year's CONTACT festival. Forgetting that my reasons for this might have been somewhat dubious, it posed an interesting problem in terms of my selection process. Obviously I wanted to pick galleries that were close to one another, but I also wanted to make sure that there would be some thread between each show that I could tie together in my subsequent posts.

Theoretically speaking, the festival is organized around the central theme of 'still revolution.' But, due to the sheer number of exhibitions on offer, they don't all explicitly relate to this guiding principle/idea. The exception to this is the feature exhibitions, which tend to explore the theme in more explicit terms. That's not to say that they're necessarily better - there really are some great open exhibitions out there - but that the curatorial process is more controlled. So, to relate this to my original point, I decided that I'd check out some of the feature exhibitions as my first shows.

I've already shared my thoughts about Susan Dobson's engaging exhibit, Retail, so today I'll reflect upon the other two shows that I attended, Andrew Wright's Still Water and Geoffrey Pugen's Another Side of You.

Having been fascinated by the image and description of Wright's show in the festival guide, I was keen to see his work in person. I think that with photography there's a tendency for viewers to be more content with reproductions of images in book or magazine form than they would be with works in other mediums, like painting for example. Some of the reasons for this are obvious, but with Wright's current work it's critical to have a look at the installation of the pieces in the gallery space. You see, the centerpiece of his exhibition at Peak Gallery is actually better described as a photo-sculpture than as a straight photograph. His series of four small waterfalls shot at night are given depth by being mounted on structures that are, when looked at from the side, a cross between the letter "J" and "L."

The effect of this curvature at the bottom of the image is quite fascinating. As you peer at it, the direction of the water flow becomes very difficult to determine. Indeed, if the viewer wasn't aware that he or she was looking at waterfalls, I think it would be near impossible to know exactly what's going on. Thankfully for me, Wright was on hand to explain exactly what the images depict. I have to admit, however, that he had to do so twice before I could "see it." (So take that as a little warning about my credibility!)

As intriguing as this is visually, it's also important to note the degree to which these images function as a temporal metaphor. Recalling the festival's theme of 'still revolution,' and the exhibition's title, Still Water, the complexities and ambiguities related to the flow of the waterfalls implicitly gesture to the strange relationship the photograph shares with time. On the one hand the photograph is said to "freeze" time, to capture and hold an instant. But, on the other, photographic images always invariably gesture to what's outside the frame, to the wider temporal context in which they were taken. A photographer doesn't just compose an image on a spatial level, he or she chooses that 'decisive moment' to open the shutter. And, the conditions that led to this decision are forever preserved in the image produced in that moment, if only implicitly and subtly.

So, as his title suggests, what Wright presents to us are indeed images of 'still water,' frozen in his series of photographs. But, we know that the water must be moving. And our desire to determine the direction in which it flows gestures nicely to the way in which photographs function to fashion our historical consciousness. Photographs preserve and contain the past, but by doing so, they also ensure that we maintain a continuous relationship with it. This draws past and present into a relationship that defies simple linearity. At the risk of being overly theoretical, I'd call this connection dialectical: each element mutually determines the other. We always view the photograph from the present, but the past it depicts shapes that very moment of viewing. I think Wright's images deftly suggest this complex interplay.

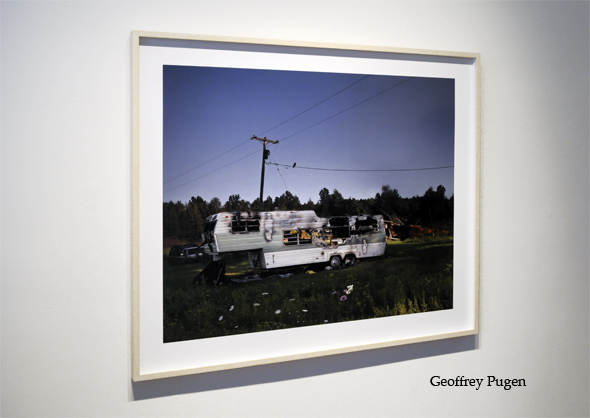

There's an obvious segue to Geoffrey Pugen's work here. On display at Angell Gallery, Pugen's work features images that are manipulated to create incongruous juxtapositions between their visual elements. Although not a commentary on time, they also draw a certain conventional understanding of the photograph into question. Despite the technological advancements in digital technologies over the past twenty years, many still invest faith in the idea that photographs must strive to provide a neutral depiction of reality.

Against this longstanding tradition, more and more fine art photographers are embracing the idea of wholesale manipulation of their images. Pugen fits squarely within this group, and from a technical standpoint, he's extremely good (I'll reserve conferring the status of master to heavyweights like Jeff Wall and Andreas Gursky). Perhaps best known for his images that fuse animal and human forms, Another Side of You also works to bring together seemingly incompatible elements through seamless stitching of different images.

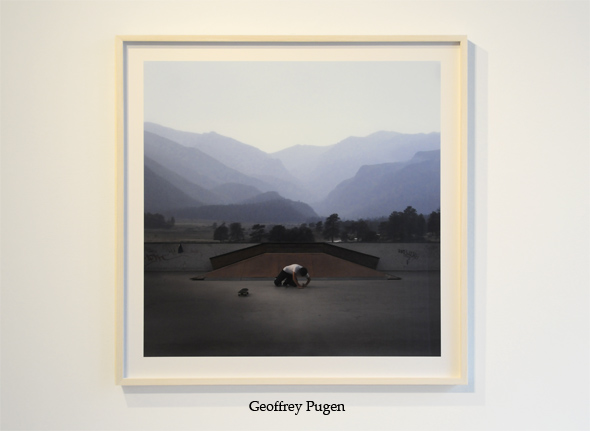

Take, for instance, the first of his images that I encountered at the gallery. A picturesque capture of a skater who's fallen off his board, at first there seemed to be nothing particularly remarkable about it. In fact, I actually moved on to his next piece before it struck me that there must be a manipulation somewhere in there. You see, Pugen's work comes advertised in this capacity, so it's common to see gallery-goers virtually pressing their noses against the glass to spot what has been altered or added.

So, returning to it, I realized that there probably aren't skate parks built in such bucolic surroundings. My bet is that two photographs are stitched along the line that separates the foreground from the background. Other images, like the one of a car submerged in a suburban swimming pool, also operate by challenging the viewer to imagine the strange circumstances the might have led to such a thing.

The description in the festival guide notes that "[i]n an age of technological transformation, Pugen's modified prints blend reality with mythology as a strategy for social critique." I think that this more aptly describes his prior work with animal/human forms, of which one piece is featured in this show. The majority of the images featured in Another Side of You don't strike me as particularly critical on a social level. The clever combinations featured in Pugen's work may hint at certain tensions by eliciting puzzled reactions on the part of viewers, but that's not quite the same thing.

The interrogations that Pugen's work provide are more theoretical and philosophical, asking us to question what we take as real, and the degree to which we can trust the images that saturate our culture. In essence, digitally manipulated images make explicit what has always been implicit regarding the photograph's relationship to truth: to some degree or another, they depict what the photographer wants us to see.

Andrew Wright's Still Water and Geoffrey Pugen's Another Side of You run until May 26th and 30th respectively.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments