The history of the Cayuga steamship that once sailed from Toronto to Niagara Falls

It's rare that a ship is ever referred to as an architectural treasure, but I believe that the old Cayuga, which sailed from Toronto harbour each summer for many decades, perhaps qualifies for this distinction.

Similar to a building, it required a designer and a myriad of craftsmen to complete its construction.

Launched on 3 March 1906, the Cayuga’s maiden voyage was in 1907. It was named after one of the tribes of the Six Nations Confederacy. The SS Cayuga was capable of carrying nineteen hundred passengers.

Twin screws propelled it, which were considered a marvel in their day. Most ships, including the Toronto Island ferries, employed side-paddles for propulsion, which generated far less speed.

During the sailing season, the ship was an integral part of the life of Toronto as it was the main method of journeying to the Niagara Region.

Below its decks, it transported cars, trucks and cargo. During the closing weeks of summer and early autumn, the ship brought fruits and vegetables from the Niagara region to the markets of Toronto.

Most Torontonians considered their summer incomplete if a voyage on the Cayuga were not included. During the years the ship was in service, it carried over 15 million passengers across the lake.

Perhaps the most famous of them was the Prince of Wales, later to become King Edward VIII, who crossed from Toronto to Queenston in 1927.

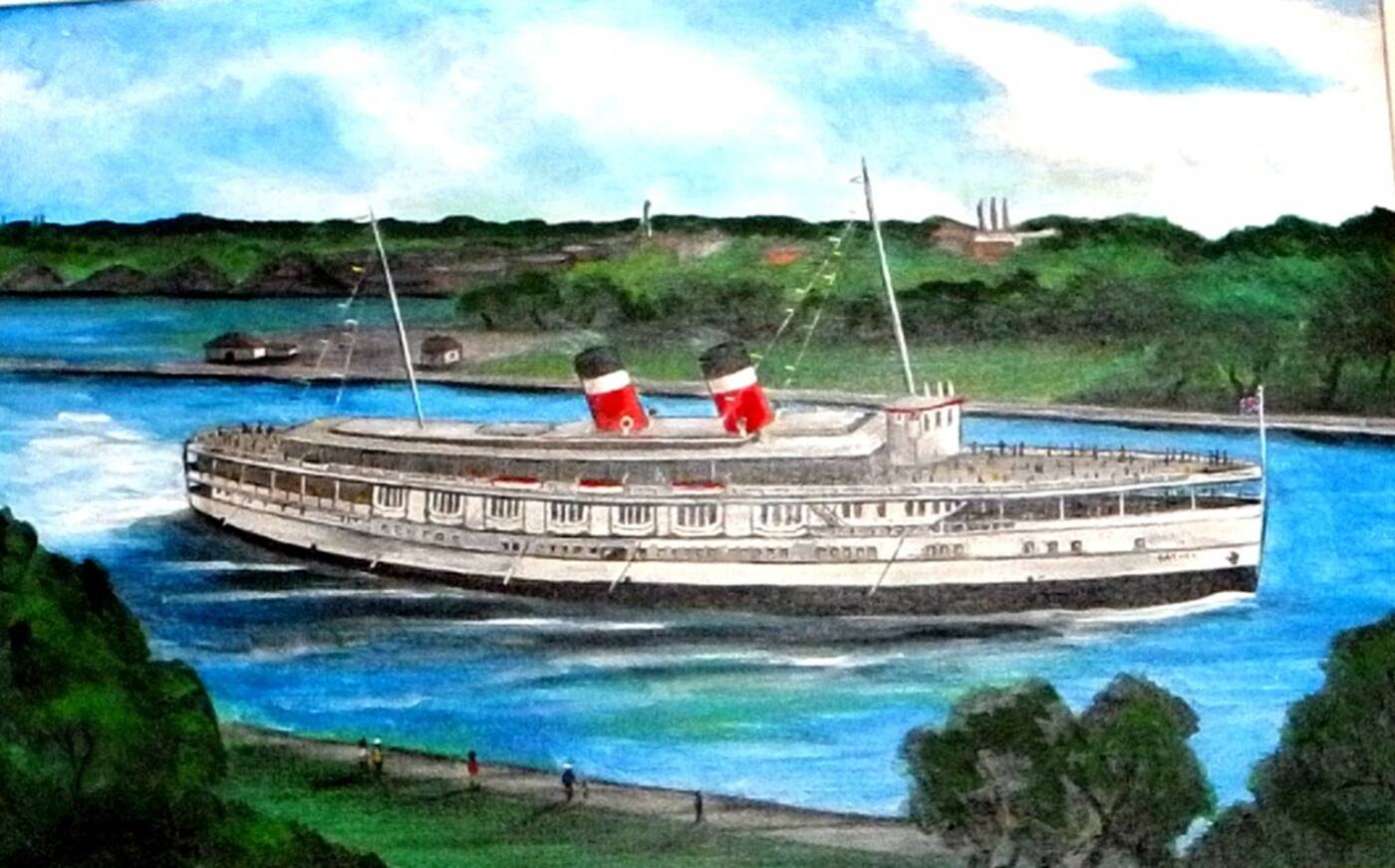

The painting shown above depicts the vessel steaming through the Eastern Gap on a July morning as it commenced its voyage across Lake Ontario to Port Dalhousie.

The ship sailed from the wharf at the foot of York Street. Tickets for the SS Cayuga were purchased from the office of Canadian National Steamers.

In the 1940s, fares were one dollar for adults and fifty cents for children, the war taxes being extra. The ship departed at 9:15 a.m. for a two-hour crossing to Port Dalhousie.

The crowds brought along bicycles, picnic baskets, and sometimes yapping dogs. The ship's polished oak rails and gleaming decks were a sight to behold. When the ship sailed out of harbour, it dwarfed any Toronto Island ferry that it passed.

On the outside decks were long, rows of wooden benches to accommodate passengers. On the outgoing voyage, the best seats were on the port side, where the early-morning sun dispelled the chill in the air, and later, when the day warmed, the overhanging the deck above protected passengers from the heat.

The port side also provided a panoramic view of the city’s skyline as the ship sailed across the Toronto harbour toward the eastern gap.

In the 1940s, the massive Royal York Hotel, the towering Bank of Commerce, and the clock tower of the Old City Hall at the top of Bay Street, and the spire of St. James Cathedral, all reached high into the summer sky, no other buildings able to rival their soaring heights.

After sailing through the eastern gap, the ship entered the open waters of Lake Ontario and the captain set a southwest course. In the lounge inside the ship, there were more wooden benches.

The ship also boasted a dining room and a dance floor that rivalled those of the finest hotels in Toronto. At the stern section of the lounge was a snack bar, where the crew sold coffee, tea, soda pop, and hot dogs.

A sign indicated that the Cayuga was a "dry ship," as wine, beer, and alcoholic drinks were not available. However, there were always a few men with bulges in their back pockets, not caused by overly thick wallets.

Some passengers frowned upon the behaviour of these unsavoury characters, certain that they were carrying hip flasks. The ship was not as "dry" as the sign in the lounge indicated.

A grand staircase led from the lounge to the deck below. Halfway down there was a landing where the staircase divided, one side extending to the left and the other to the right.

At the bottom, on the left, passenger walking toward the stern could peer through an open door that looked down into the engine room. They were able to watch the throbbing monster engines that powered the ship.

Heat, steam, noise, and the odour of diesel oil were infused into the air. It was an awesome sight. Originally, the ship had been powered by coal, but it was eventually converted to oil.

The famous steamship Cayuga. Heavy black smoke coming out of the stacks - it was a coal burning ship till 1946 when it was converted from coal to oil. Photo by Kenneth E. Smith.

The "Gents" room was another sight that was impressive, especially to younger boys. White basins sparkled in the morning light that shone through the portholes, which possessed gleaming brass fittings.

The huge, ivory-white urinals were so deep that many a young lad felt in danger of falling in, and that if someone pulled on the brass handle, they might be flushed into the lake.

The urinals were the equal of those in the basement of the Eaton’s store. Some lads wondered why such massive structures were necessary, thinking that they might be more suitable for a horse with a kidney problem.

If the weather cooperated, there was nothing so glorious as leaning on a rail of the Cayuga's deck, gazing out over the water. If it were a sunny summer day, the sight was amazing—smooth waters and azure skies, with distant puffs of clouds hovering near the horizon.

On such days, the lake resembled an enormous pond, the dazzling sunlight reflecting from its glassy surface. Within a half hour of the ship’s departure, the heat of the sun forced those who had earlier stood at the rails, to retreat to the recessed areas under the shade of the decks.

There, they were able to sit in comfort and enjoy the view.

When the ship finally arrived at Port Dalhousie, the crew tossed the thick hawser ropes to the men on the dock, who attached them to the bollards.

In warm weather, the ship was greeted by young boys who had gathered at the dock to watch the ship arrive. After they had moored the vessel to the wharf, they dived into the water to retrieve coins thrown by the passengers.

This ritual occurred again when the ship embarked on its return voyage to Toronto.

Sadly, the mighty Cayuga was unable to attract sufficient passengers after people acquired automobiles and were able to drive to the Niagara Region, rather than sail across the lake. It went to the scrapyard in 1960.

However, when built, it was an engineering marvel, in its way a rival to the grand buildings that were erected in the same decade in which it was launched. I believe that it qualifies as one of Toronto's lost architectural gems.

Doug Taylor was a teacher, historian, author and artist who wrote extensively about Toronto history on tayloronhistory.com. This article first appeared on his site on April 6, 2013 and has been republished here with the permission of his estate. The article has been modified slightly.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments