Nostalgia Tripping: Trefann Court

While doing some research for last week post about Alexandra Park, I realized that for some time, I've also been planning to write about the events that led to the successful preservation of Trefann Court, a community that managed to stem off the destructive nature of postwar urban renewal. Along with a small section of River Street, it is one of the surviving remnants of (old) Cabbagetown, of which ninety percent was torn down in the 1940s and '50s to make way for the north and south sections of Regent Park.

Trefann Court is a residential neighbourhood, located east of Yonge Street and south of Regent Park South. It is bounded by Queen, Parliament, Shuter, and River Streets. According to Graham Fraser's Fighting Back: Urban Renewal in Trefann Court, it derives its name from one Trefann Street, which is located in the eastern part of the neighbourhood.

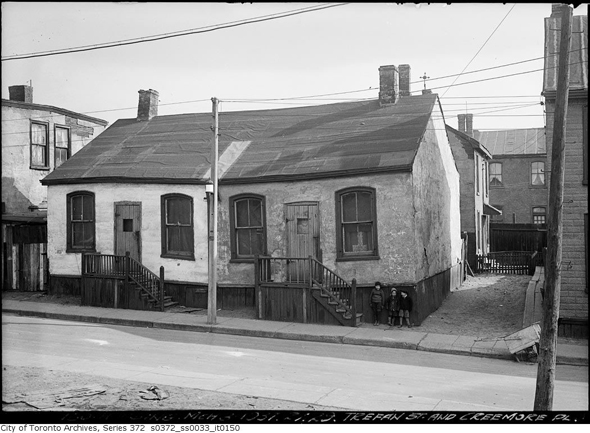

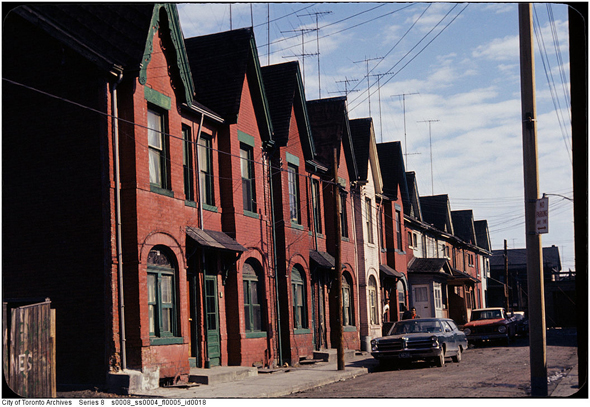

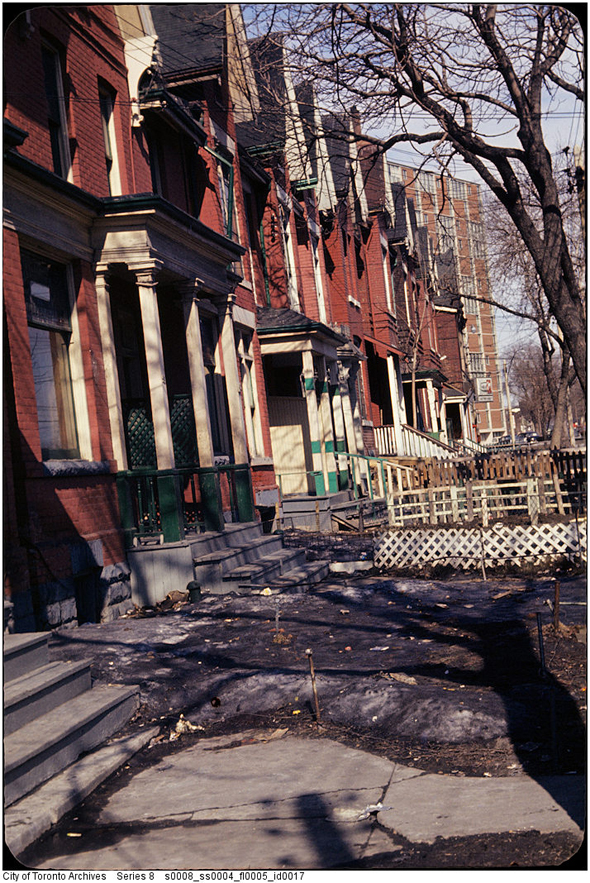

Following the construction of Regent Park, the craze for inner-city revitalization went further: in addition to Trefann Court, the city also eyed Don Vale (now referred to as Cabbbagetown) and Kensington Market as possible candidates for demolition. In the 1950s, the area was characterized by its nineteenth-century row houses, industrial plants, and retail stores near Queen and Parliament Streets. There was also a new industrial structure at Sumach Street. It was a working-class neighbourhood, which unlike the nearby Don Vale, did not possess a quaint Victorian charm, and did not attract any middle-class residents.

The plan for the reconstruction of the neighbourhood, designed by Eugene Faludi in 1956 and prepared for Industrial Leasehold Co. Ltd., the owner of the industrial building, along with city-approved schemes, included the demolition of all residential buildings in the area. The western section of the area would be used to build new housing, while the eastern part would be sold off for industrial purposes.

This proposal was unveiled 10 years later (in 1966) and immediately drew criticism from the residents, who for the next four years demonstrated against it and proposed that the existing structures, which although were run down, could be rehabilitated. During that time, Sewell, a law student, became involved, and emerged as one of the most vocal opponents of the first urban renewal proposal for the area.

However, these complaints were largely ignored by Philip Givens, who was mayor at that time, and city council. As demonstrated by the construction of Regent Park, resident participation in the process of city planning was not traditionally taken into account.

Following the municipal elections in 1970, during which Sewell was elected as alderman, new council agreed that any plans for the area had to include consultations with the residents and business owners.

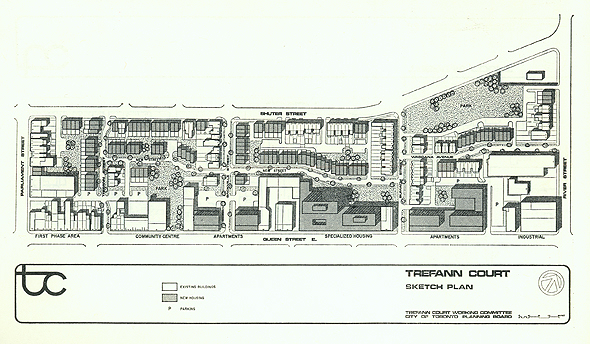

Trefann Court came to symbolize the end of urban renewal schemes not only in Toronto, but also across Canada. According to Sewell in The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning, three important changes in urban planning were implemented. First, all of the old proposals for the neighbourhood would have to be abandoned and a working committee consisting of residents and business owners would be responsible for drawing up new plans. In Sewell's words, "The idea that ordinary people could be involved in city planning was a major blow to the new suburbanist approach, which relied on experimentation, total clearance, and the mysticism of the private planner."

Second, the residents secured the right to choose the planner, with whom they would collaborate in creating the plan. They first requested that the planner's office to be located in the neighbourhood, but the city officials argued that this would impede planning professionalism and independence. Nonetheless, they backed down under pressure and even allowed the residents to participate in staff selection.

Third, the final plan, as developed by the working committee, was fundamentally different from the original plan drafted by private developers. It preserved and extended the existing street system, proposed sites for new housing on empty lots with front and back yards, and called for replaced of structures that were severely damaged. Today, Trefann Court is an interesting mix of nineteenth-century structures as well as low-rise buildings that jointly reflect the character of the neighbourhood.

Images from the City of Toronto Archives.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments