Toronto reimagines the public park for the 21st century

It's widely agreed that Toronto began an architectural renaissance in the early 2000s, which brought with it a slew of buildings that helped to restore the city's waning reputation after the depths of the '80s and '90s early condo boom that added little of intrigue to our built legacy.

Even if they're not universally loved, buildings like the Sharp Centre for Design, the ROM Crystal, and Frank Gehry's AGO revamp got the city talking about its architecture with a fresh energy, a conversation that continues today with an unmistakable passion.

In a city that seems always in a state of becoming something great, the design of new buildings is important stuff.

A similar rebirth is now taking shape with Toronto's park spaces. Gone are the days when an outdoor space is conceived as a grassy expansive with a few benches and a playground. As the city has become more and more dense, the design of its parks has become more and more inventive.

This process can probably be traced back to Claude Cormier's HTO Park, which repurposed industrial lands as an urban beach and served as an important precursor to the widely loved Sugar Beach, the latter of which almost entirely dispenses with the use of grass.

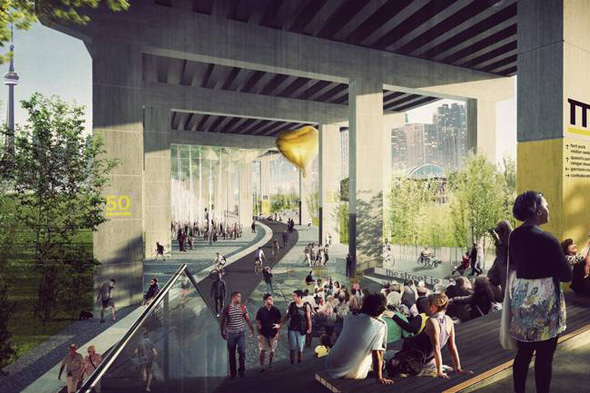

Working with smaller sites has forced architects and landscape designers to move away from traditional models of parkland in favour of urban spaces that are high on usability rather than sheer open area. Perhaps the best example of such a project is Underpass Park, but the design principles seen there can be spotted in most new spaces, even those with far more greenery.

Take, for example, the award-winning Corktown Common. Instead of plopping down a huge field in the middle of a major residential development, the park is built atop the Flood Protection Landform for the Canary District, and thus features plenty topographic variety to go along with a wetland pond, boardwalk path, splash pad and modern playground.

The idea here is to provide as diverse an experience for the park user as possible. This sentiment is also seen in the early plans for the Bentway (formerly the Under the Gardiner Project), which envisions the space under the expressway as more than just sporting areas but as a series of rooms tied together by a central recreational path and public gathering spaces.

Even more humble spaces reflect this new way of thinking about parks in Toronto. The soon-to-reopen Berczy Park has been designed with a dog-theme as part an effort to make it a more friendly place for pet-owning condo dwellers in the area. It's divided into three zones, each of which reflect different users from kids to canines.

In the past, the park was mostly conceived of as a spot for office workers to eat lunch or tourists to rest while exploring the St. Lawrence Market area. Now, it must cater to a wider range of uses given the changing demographics of the neighbourhood.

This shift in thinking is also about aesthetics. Aga Khan Park, for instance, is more a zone of contemplation than it is a traditional Toronto park, complete with gardens and a long reflecting pool. Similarly June Callwood Park near Fort York is meant to be an urban forest rather than an open space.

Even the revitalization efforts at Grange Park, one of the few examples of a new park space that will remain dominated by a central grassy area, work toward diversifying the way the space can be used, from the addition of a new entrance to the AGO to water fountains and gardens, as well as modernized playground infrastructure.

All of these projects have laid the groundwork for what might be the most important of them all, the recently proposed Rail Deck Park. One doubts that the idea for such a public space would have been dreamed up in Toronto had these predecessors note shown the potential in deviating from conventional park designs.

We don't yet know if the Rail Deck Park will come to be, much less what it will look like, but it too serves as a glaring example of the degree to which Toronto has reimagined the role of park space over the last decade.

Let's hope we continue to build on the work done so far.

Photos by Robin Hamill Photography, Claude Cormier & Associates, and the City of Toronto.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments