That time GO Transit almost went electric

GO Transit has been promising to electrify its trains for a long time--the provincial Liberals have promised to get it done (eventually) and mayoral candidate John Tory is making "surface subways," electrified portions of the Metrolinx network, part of his 2014 election platform.

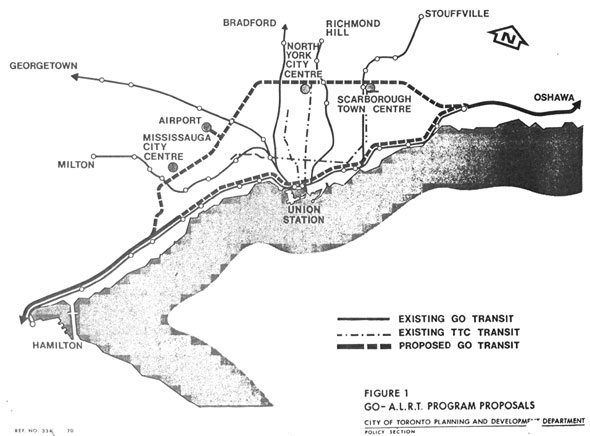

The idea isn't a new one. One of the first incarnations of high-speed, non-diesel GO transit surfaced in 1982 with the announcement of GO-Advanced Light Rapid Transit (ALRT)--a plan to install trains similar to the ones used on the Scarborough RT on a pair of east-west routes through the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area. The result would have been a second tier of GO transit, smaller in capacity but faster and more frequent than regular inter-city service--roughly every 5 minutes, down from 20.

At the time of the announcement under premier Bill Davis, GO was paying steep rental fees to share rail lines with CN freight locomotives. By buying up land parallel to the CNR line, GO predicted it could save millions in charges and boost reliability at the same time.

The basic concept originated from a very Toronto pastime--idly drawing transit lines on a map. Provincial minister of transportation James Snow was returning from a fishing trip in Halifax in the summer of 1981 when he and a colleague discussed the idea of a new type of rapid transit for the GTHA.

"Flying home, he and his deputy minister, Harold Gilbert, started talking about Toronto's commuter transit problems," Mark Osbaldeston recalls in Unbuilt Toronto 2. "Using magic markers and some handy maps, they blocked out a solution, a route for a commuter transit network serving the GTA and beyond."

The result was a plan for two lines: one in a new right-of-way between Oshawa and Hamilton and another parallel to the 401 corridor between Oakville and Pickering with a spur to Pearson Airport. The trains would be similar to the ones the province's Urban Transportation Development Corporation had developed for the Scarborough RT, minus the futuristic magnetic induction motors.

Like the Scarborough Intermediate Capacity Transit System (ICTS,) the GO-ALRTs would be computer controlled and operated on an elevated guideway at speeds of up to 70 km/h. (As Transit Toronto notes, the trains would later go through several design changes, starting off similar in appearance to the ICTS and later appearing as longer, articulated vehicles with seating for more than 120.)

The whole thing--trains, track, land--was projected to cost about $3 billion and it take 20 years to fully complete.

The first phase would see the existing Lakeshore GO line extended beyond its eastern terminus at Pickering to Oshawa by 1988. The first electric trains would only operate between those two stops. Later, at the west end of the line, ALRVs would run between Oakville and Hamilton while a downtown link track through Toronto's Union Station was under construction.

Premier Davis predicted 22,000 people would ride the Pickering-Oshawa extension every day, 12,000 between Oakville and Hamilton. The entire GO network carried about 100,000 daily in Nov. 1983, but traffic was becoming an increasingly pressing issue in Toronto. In an attempt to better integrate the TTC and proposed GO-ALRT, officials discussed establishing a single fare for the two systems.

While the eastern portion of the new Lakeshore line was broadly welcomed, the Hamilton end became mired in trouble. The proposed route would have taken the ALRT down Highway 403, through a brand new park, under the city cemetery, into the downtown at the expense of 11 houses. Local residents formed a protest group called "NO-ALRT" in opposition to the alignment, much to the frustration of transportation minister Snow.

If Hamilton chooses "a white elephant route that doesn't meet transportation standards, that's no good to us," he said.

The Pickering-Oshawa extension broke ground in June 1984, but costs were already creeping up. The $162 million budget for the 25-km extension hit $350 million before shovels entered the ground. Snow put on a brave face, dismissing observers who predicted the ALRT would soon be nixed. "My faith in the feasibility of an electrified rail system running along the lake shore ... with links to municipal transit and a second inter-regional line stretching north across Metro remains unshaken," he said as the bulldozers began their work.

Like so many GTA transit plans, the ALRT was killed by a change in the political climate. By 1985, premier Bill Davis was out, as was transportation minister James Snow. The incoming ministers cancelled the electric trains, opting instead for diesel. They did, however, decide to keep the east-west Lakeshore GO corridor extension, saving $100 million and speeding up the opening date.

On his blog, Toronto transit advocate Steve Munro says the GO-ALRT was "flawed at heart."

"There is a long history of our transportation plans and needs being highjacked or misdirected, and GO-ALRT was a classic example," he wrote in 2007. "On the premise that nothing could fill the place between a bus and a subway at reasonable cost, Queen's Park set out to invent a new transit mode, to fill a "missing link" in the evolution of transit."

"The GO-ALRT network was visionary in hoping to build regional infrastructure before the regions actually existed, but it foundered on the need for a new technology to be developed, perfected and implemented at reasonable cost."

As Osbaldeston writes in Unbuilt Toronto 2, the scheduling problem with CN trains also conveniently vanished in the mid-1980s, taking with it the main justification for the dedicated right-of-way.

"GO-ALRT had become a solution to a problem that no longer existed."

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: "GO-ALRT," 1983, City of Toronto Archives, Series 1465, File 597, Item 38; "The GO-ALRT program: Status Report," June 30, 1983, Toronto Public Library, 385.22097 G566; Toronto Star, June 20, 1984, A26.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments