That time a giant gas balloon dazzled Toronto

In mid 19th century, more than 40 years before the Wright Brothers' first successful airplane, gas balloons were the only devices capable of flight. Susceptible to wind, storms, and incredibly frail to the slightest trauma, anyone willing to climb into the basket and cut the ground tether had to be fearless and a touch crazy too.

Professor John H. Steiner was just that person. A German-born aeronaut, Steiner arrived in North America in 1853, bringing with him a working knowledge of the experimental field of gas ballooning. Over the next 30 years, the fearless and persistent pioneer would risk his life to fly over Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, both trips providing exciting accounts of high adventure relished by those on the ground.

In 1859, from a patch of vacant land opposite today's Union Station, Steiner would make the first ever Toronto aerial ascent in a simple gondola tied to the bottom of a home-made hydrogen balloon.

The danger was huge, a crash had almost led to his drowning just months earlier, but he went anyway.

70 years earlier, in 1783, Professor Jacques Charles and brothers Anne-Jean and Nicolas-Louis Robert has launched the world's first hydrogen-filled balloon from the Champ de Mars, later the site of the Eiffel Tower, in Paris, but the unpredictable branch of aviation had yet to realize its promised potential as a means of transportation.

The French group produced hydrogen by pouring sulphuric acid over scrap iron. The resulting vapours were captured in a red and white silk balloon measuring about 35 cubic metres. Once released, the colourful sphere was carried more than 21 kilometres on the wind pursued by a group on horseback. It was, however, eventually attacked and destroyed by a gang of terrified villagers before the chasing pack could catch up.

A manned flight in a hot air balloon took place later that year, organized by another pair of brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etienne Montgolfier, in Annonay, France. As a result, François Laurent d'Arlandes and Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier are credited as the first to see the ground recede from the rail of a balloon gondola.

In the United States, Professor Steiner's best known early flight was an attempted crossing of Lake Erie to Canada. Although they resembled modern hot air balloons, the precarious contraptions piloted by Steiner and his fellow aeronauts had more in common with dirigible airships, like the one that famously visited Toronto in 1930. Instead of heated air, gas balloons achieved buoyancy using a lighter than air gas, such as helium or hydrogen, held captive in a large textile bag.

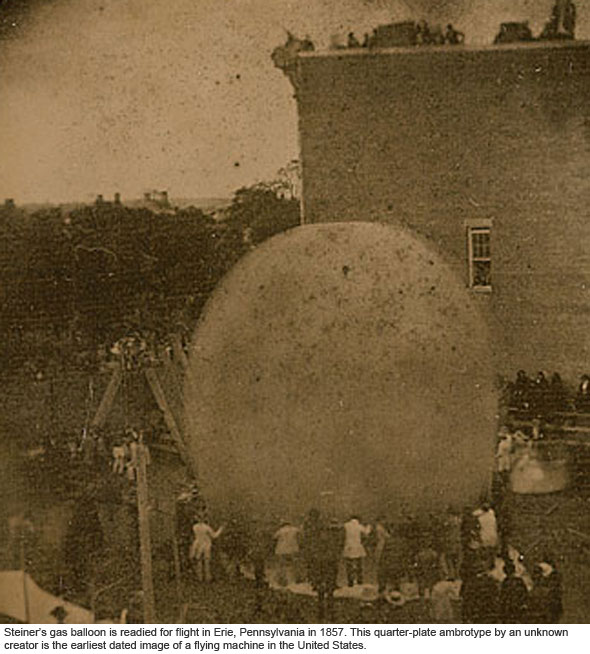

In 1857, Steiner and a team of assistants filled a simple fabric balloon with hydrogen on a small patch of scrubby grass in Erie, Pennsylvania. A crowd gathered on a nearby rooftop as a group helped support the growing orb, which looked like a giant egg being raised by brooding adoptive parents.

Cut free, the wind carried Steiner northwest toward gathering clouds over Long Point, Ontario. Out on the water, sail boats and steam ships sounded their horns and saluted the strange flying machine. Just out of sight of land, the deepening gloom had formed into a crackling lightning storm. The wind picked up and began jostling Steiner's balloon, thumping into the fabric and shaking the gondola.

"Oh! What a scene was transpiring around me," he would later recall. "Every moment the surrounding masses of clouds were illuminated by flashes of lighting, succeeded by terrible crashes of thunder, in the very midst of which I seemed to be floating, and my excited imagination led me to fancy that I would feel my frail car quiver at every shock."

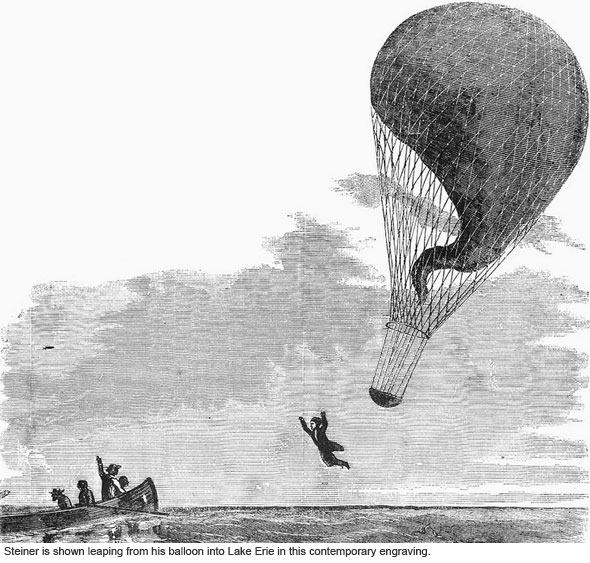

Moments later, with the rain streaming in his face, the balloon began to lose altitude and skim the water. The captain of the Mary Stewart, a steamship bound for Detroit, sighted the ailing vessel repeatedly slapping the roiling surf and climbing in to the air at a 45 degree angle. 40 kilometres off Long Point, the ship sounded its horn and Steiner responded by waving an American ensign.

"We were all astonished as his daring recklessness, striking the water and rising to a height of fifty to seventy-five feet, and descending suddenly again to the surface of the water with such force that we were apprehensive for his safety," the captain wrote in his logbook.

Steiner jumped from the foundering balloon into the churning water and was hauled out just as a crew member from the Mary Stewart had managed to grab hold of the basket. He gamely held on for a few seconds but the wind was too strong. It slipped from his grasp and "disappeared before the gale." It would be found days later in shreds, just inland.

Despite the Erie mishap, Steiner was confident balloons could be safely adapted for passenger service and used to cross the Atlantic Ocean, potentially cutting the weeks-long crossing to just a few days. Until then, the airships made for a great spectacle but little else.

A year later, in an attempt to whip up excitement for ballooning and pocket a little cash at the same time, Steiner and his friend, French professional aeronaut Eugène Godard, organized and set about heavily promoting a one-off racing derby.

Godard in particular had fallen on hard times and desperately needed a way to revive his fortunes. 40,000 people attended the start of the race in Cincinnati, Ohio and a huge cheer went up when the pair collided high above the town over its outskirts.

The pair fought each other off with "chivalric gallantry," though at 4,600 metres the crowd can't have seen much. Despite their unexpected entanglement, the two raced for over 320 kilometres with Steiner eventually emerging as the winner. The cash injection from ticket sales kept Godard flying - he would later invent a tear-off panel for instantly deflating a wayward balloon and make the first ascent with a passenger in Quebec.

That same year Steiner built a larger balloon named the Europa and, after a handful of tests, packed it up for Toronto.

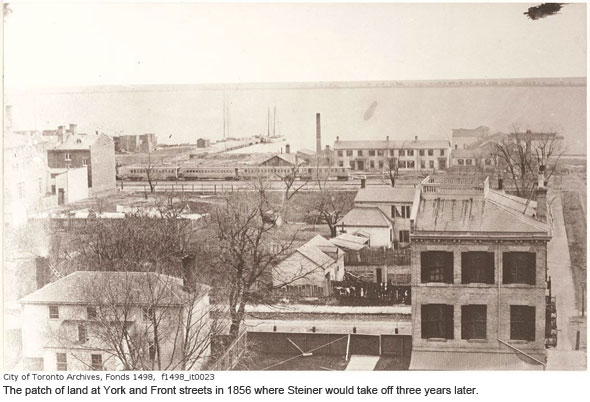

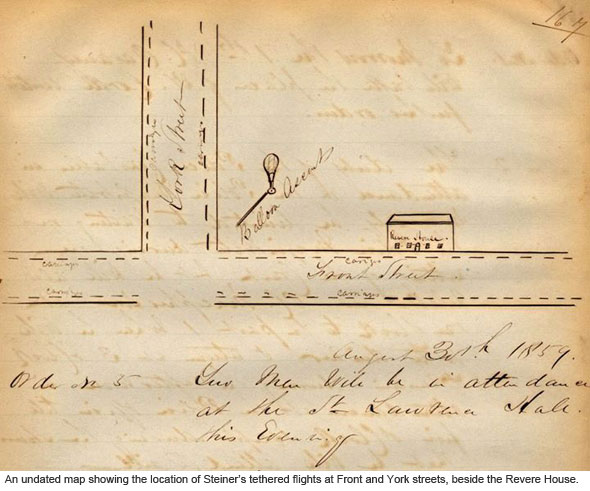

Steiner arrived in August 1859. The city he found was full of brick homes with pitched roofs, few of them over three storeys. Trees, church spires, and the dome of Osgoode Hall shaped the skyline. On a vacant patch of ground on the northeast corner of York and Front, later the home of Harry Piper's Zoo, he began stitching together his giant balloon.

Fully inflated, the Europa stood 20 metres tall, about a third the height of the newly-completed Cathedral Church of St. James. It was 60 metres around at its widest point and could hold a massive 566 cubic metres of gas.

Nothing like it had ever been seen in Toronto before and Steiner expected to make money taking passengers on "topical" - his word for tethered - ascensions to around 152 metres, about the height of the CIBC tower at Yonge and Bloor.

He also banked on money from railway companies and local hotels who would see a bump in business during the spectacle, he claimed. At the end of August, Steiner would depart for "some point between New York and Boston" via Oswego. Controlling a floating balloon was practically impossible and targets difficult to reach accurately.

On August 25, after a few weeks ferrying weak-kneed passengers from the stifling heat of the ground to the cool breezes high above the chimney tops, Steiner was ready to leave. Inflation began at 1:00 that afternoon with a hook up from the Revere House hotel and took around four hours to complete.

At 4:20, the last tether was removed and a crowd of well-wishers waved the silent giant and its lone pilot farewell. It rose quickly and drifted southeast towards Ashbridges Bay; before long the balloon became a silhouette as it broke through 1,500 metres.

"There were but a few clouds in the sky and those reflecting the beams of the setting sun were unspeakably magnificent. For many miles the American and Canadian shores were discoverable; the various towns and villages resembling pearls upon an emerald ground," he would later write.

As the sky grew dark with night, Steiner recalled how the lanterns from ships on the surface of the lake became his only reminder of his proximity to the ground. As the hours slipped past, clouds began to form, no doubt reminding the pilot of his experience over Lake Erie.

At 2,750 metres, the air chilled considerably and Steiner pulled on his overcoat. The lights from the water below were now joined by the the flashing crests of rolling waves. Ballast was thrown overboard as the balloon naturally retreated to a lower altitude, and again as the winds climbed and clouds grew darker.

The temperature continued to plummet in the rarified air; his exposed hands went numb first, then the tips of his ears. Huddling in the bottom of the basket, Steiner remembered he had tied off the throat of the balloon on departure for maximum buoyancy but had forgotten to release the required amount of gas for level flying.

His aching ears indicated a dangerous climb that needed to be arrested, quickly. He sprang up and pulled the knot loose, releasing a rush of suffocating hydrogen that blasted him directly in the face. With the balloon stabilized, the storm clouds and the threat of damage dissipated. "The stars twinkled in the clear heavens."

Soon, the lights of Oswego shimmered into view on the horizon and Steiner began to prepare for a complicated descent. He suspected the wind below his present station was blowing north, back towards the lake, and wanted to avoid it until the last moment. Were he to be caught in a sudden breeze there would not enough remaining gas to affect a return and the trip would end in another untimely soaking.

First the ballast bags were heaved over the rail of the gondola, then the cloth case used to transport the balloon, then the metal trimmings on the car, even the blanket which not so long ago had sheltered him from the elements. Still the balloon continued to descend too fast.

Finally, his hands still stiff and grey from the cold, the iron anchor used to tether the balloon to the ground crashed into the surf. The basket began to rise above the offshore winds.

Steiner watched Oswego pass underneath, its squares and chequerboard streets glowing gold, and finally let all but the last dregs of hydrogen escape. The balloon wrinkled, skimmed top of a couple of trees, and squelched in to swamp seven miles south of the town, just west of the Oswego River.

The last of its internal gases had kept the balloon from flopping to the ground and, exhausted, Steiner hauled the gondola to the nearest road and secured it to a fence, his anchor now at the muddy bottom of the lake. He walked to a nearby sawmill, still open at the late hour, and explained his situation - sadly, he didn't record their reaction.

The workers gave him a plank of wood to sleep on and at dawn he set out to find his balloon. "Fifteen or twenty country people were gazing at it in astonishment, not being able to make out from whence it had come." They looked at Steiner like he was the man in the moon.

He had traveled 260 kilometres from the foot of York Street and had become the first person to fly across Lake Ontario. The flight took 9 hours.

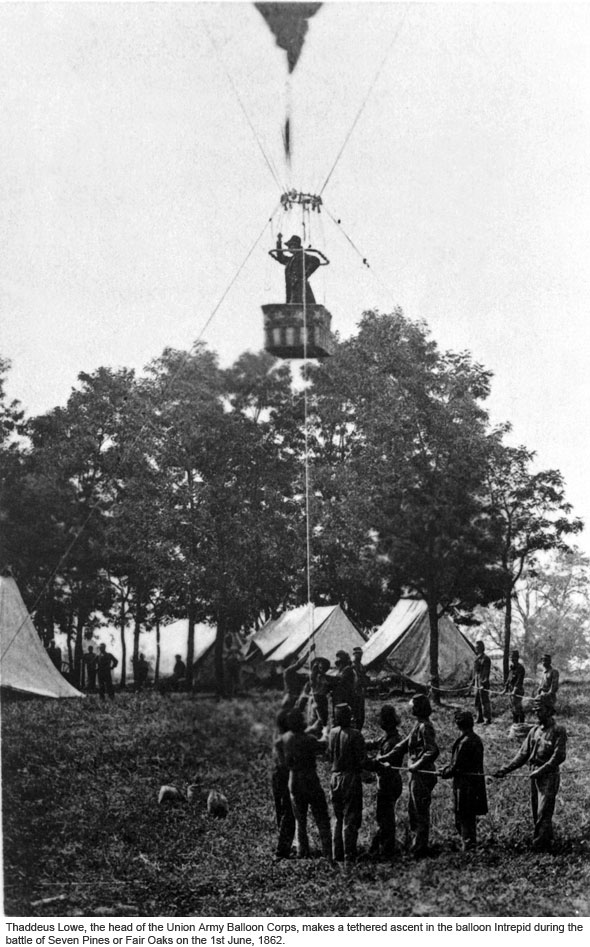

Back in America, Steiner later applied his knowledge of balloons as part of the Union Army Balloon Corps, a flying division of gas balloons that carried out reconnaissance on Confederate forces during several key battles during the U.S. civil war.

He took a young Count Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin up in one of his tethered balloons and showed him St. Paul, Minnesota from on high. It was the future general's first time in the air and they would later discuss the principles of achieving and controlling buoyancy.

The memory clearly stuck with Zeppelin. In a rare interview in 1915, he failed to recall Steiner's name but confirmed the pair had flown together in tethered and free flights that cold winter in Minnesota.

The fate of the first man to fly in Toronto is unclear. His name was overshadowed by other balloonists in the late 19th century, but in September 1873 he and his son were involved in an attempt to launch a balloon figured big enough to cross the Atlantic at the Capatoline Grounds in Brooklyn, New York.

It burst two-thirds full and was considered a major embarrassment. The balloon was fixed and did take flight only to come down in a rain storm in Connecticut, having never reached the ocean. One of its three pilots, George Lunt, fell in to a tree and was fatally injured.

It would be decades before Toronto was captivated by flight again.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: Minnesota Historical Society (lead,) U.S. Library of Congress (Robert brothers card,) City of Toronto Archives (Rossin House image,) U.S. National Air and Space Museum Archives (Erie ambrotype,) Wikimedia Commons (Thaddeus Lowe.)

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments