How Toronto got the CN Tower

The CN Tower just turned 41 years old, and you'd still be hard-pressed to name a building that's defined Toronto more powerfully. Love it or loathe it, the massive concrete structure has dominated the city's skyline and provided a visual reference since 1976.

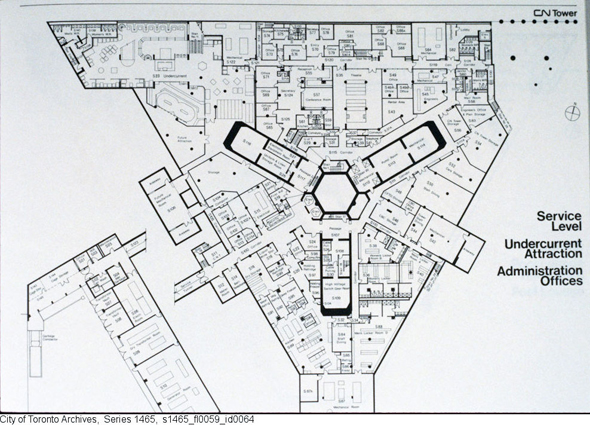

The tower itself is something of an oddity. Its practical use is as an AM, FM, UHF, and cell transmission tower, but a built-in observation deck, glass floor and rooftop fright-fest entice more than 1.5 million tourists a year up the dizzying exterior elevators.

Sydney has the Opera House and Harbour Bridge, New York has the Brooklyn Bridge, and Toronto has the CN Tower. The slender concrete column is an international icon that has made the city instantly recognizable. Few buildings are able to do that.

This is the story of how Toronto's architectural wonder came to be.

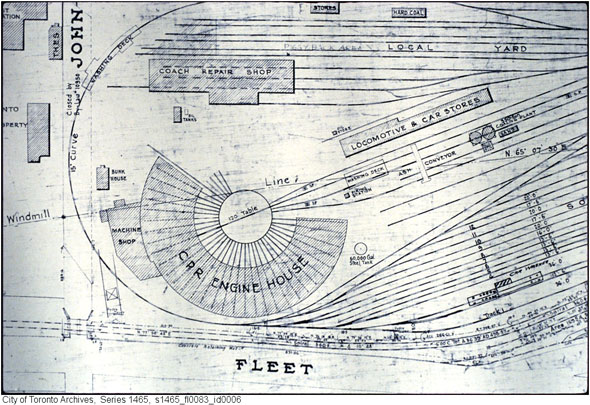

The land now occupied by the CN Tower's hexagonal foundation was, in its original form, water. Almost everything south of Front Street is built on fill, dumped construction material dropped in to the lake over the last 100 years that gradually extended the shoreline south to its present position.

The new space gave Canadian National Railways room to build a tangle of sidings, roundhouses, and train sheds around the Union Station corridor.

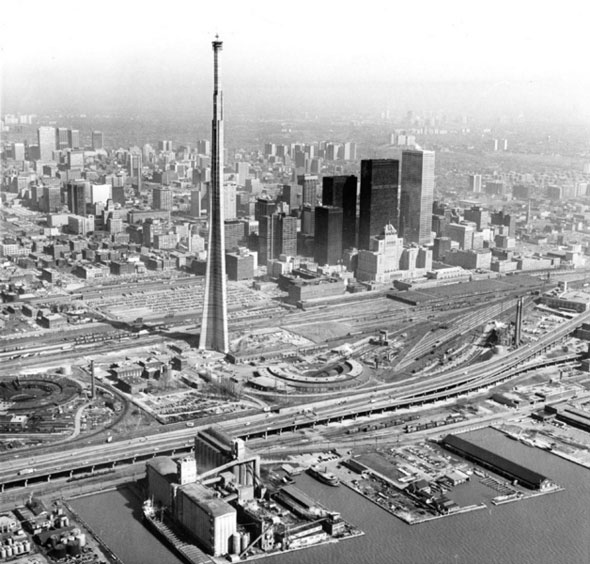

For much of its early life the reclaimed land south of Front Street was a sprawling industrial area of soot-stained concrete and surface parking. The Gardiner Expressway zipped past just to the south and silos dotted the lake shore.

It was in the 1960s, when Toronto's buildings began to head skyward, that things began to change.

As Mies van der Rohe's Toronto-Dominon Centre then Commerce Court West each claimed the title as tallest in the city, TV and radio reception became patchy and viewers increasingly found episodes of Ozzie and Harriet, Lassie, and re-runs of The Andy Griffith Show were being blasted into static oblivion.

The solution was to build a transmission antenna tall enough to beat even the highest Bay Street bank tower. The project was also a good excuse to partake in a little building bravado by snatching the title of the tallest freestanding structure from Moscow's Ostankino Tower, also a TV and radio mast.

In fact, the tower itself was one of the few pieces of the larger Metro Centre project ever to be built. Had it been realized in its original form, Union Station would have been demolished and the Yonge line would have gained a Queens Quay spur through an expansive new retail and commercial district.

Early plans for the broadcasting tower were vaguely similar in appearance to Seattle's Space Needle and developers promised a large triangular reflecting pool surrounded by a 10-acre park at the base of the tower for skating and wading. A mall and beer garden would also be built, they said.

Metro Centre died when the provincial and federal government recommended Union Station be retained and CN and CP, the principal backers, subsequently pulled out. The earmarked land would, however, provide space for the Metro Toronto Convention Centre, CityPlace, and CN's new radio mast.

At the time CN and CP jointly owned CNCP Telecommunications, a company developed out of the company's old wire service businesses, so building a large concrete signal hub wasn't entirely unusual for the transportation company.

At 553 metres, the scale of the CN Tower was immense. 56 metric tonnes of soil was hauled out of the ground for the 17-metre foundation pit. The hexagonal structural core of the tower was surrounded by poured concrete shaped using a massive mold called a slipform.

Each new section was built on top of the last, aided by a crane perched on a 500-tonne platform on top of the rising column. 1,537 workers worked on the project 24 hours a day, five days a week, from official groundbreaking ceremony on February 6, 1973.

The tower always had its detractors. The Canadian Owners and Pilots Association warned that "sooner or later an aircraft is bound to strike it possibly killing people in the tower and on the ground as well as those in the aircraft."

The Federation of Ontario Naturalists estimated 1,000 birds a day could be killed in foggy conditions during peak migration periods."We'll live to regret it if we let this monstrous dart go up," Alderman Elizabeth Eayrs told city council.

Ironically, improved reception actually had a negative impacted on some TV content. As a TV writer for in the Toronto Star predicted, the stronger signal killed the tradition of American networks releasing their new shows on Canadian television ahead of the U.S. premier in an attempt to discourage cross-border viewing.

The added range from the new CN transmitters made Canadian signals stronger than those that used to bleed over the border from New York, which would potentially allow Americans to easily tune in to Canadian stations and catch a sneaky glimpse of All In The Family.

Despite the outcries and accusations CN was building an "obtrusive monument to itself," the gigantic, $21 million construction project was allowed by council, but not before it had already reached 300 metres in height.

By August 1973 the concrete stump was the tallest structure in Toronto and in February 1974 it claimed the crown as the tallest in Canada, taking the mantle from the Inco Superstack, a giant chimney in Sudbury.

Just 18 months after the foundations were scooped out, work began on the seven-storey observation deck, revolving restaurant, and radome - the inflatable white donut-shaped object at the bottom of the main pod where much of the communications and other electronics are housed.

CHUM-FM, CBC Radio 2 (then CBC Stereo), CKFM, CHFI, and CHIN were the first stations to move their equipment in '73.

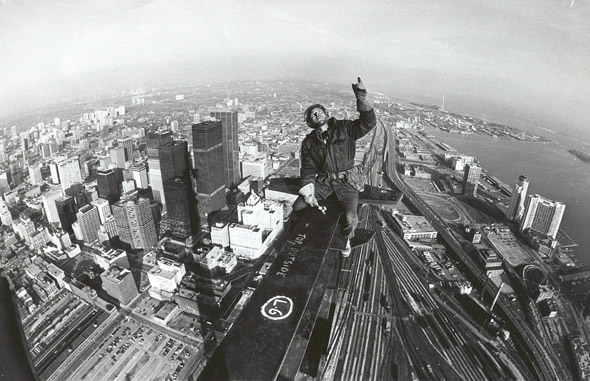

Unlike the main support column, the pod was supported by a steel frame. Dizzying photos show metalworkers straddling massive I-beams with nothing between them and a 1,100-foot drop to the rail tracks below.

Above the top SkyPod, the top observation level, a Sikorsky helicopter named Olga was called in to complete the final step - hauling up the 102-metre antenna mast in pieces from the ground. The 42 sections were delivered in March 1975 and would be the last that contributed to the overall height of the CN Tower.

Disaster almost struck as Olga was being used to dismantle the crane and construction platform that was perched at the top of the concrete core. While removing the first piece of the boom, a sudden shift caused the supporting bolts to seize, effectively tethering the aircraft to the tower.

With fuel running low, steel workers had to burn off the stuck bolts to avoid a crash. The helicopter landed with 14 minutes of gas to spare.

The incident underlined the need for adequate safety features in large freestanding towers. In the event of a fire, the main 1,776-step staircase would be one only two safe exits from the main pod.

To illustrate the dangers, on 27 August, 2000 the Ostankino Tower caught fire 458 metres above the ground, killing three people.

To combat these risks, the CN Tower is fitted with fire-proof materials and an extensive sprinkler system fed by a pair of 68,160-litre water tanks at the top of the main column. One elevator is powered by emergency generators and is designed to remain active in an emergency.

A fire house on the ground is capable of reaching the upper levels and, just to be safe, the kitchen in the restaurant doesn't use an open flame during cooking.

Naturally, the current owners are keen to stress there has never been a fire since the building opened to the public, but that doesn't mean it's never happened.

On July 8, 1975, molten metal from a welder's torch dripped down an elevator shaft and ignited a patch of tar-based waterproofing, leading to two uncontrolled fires about 150-metres above the restaurant.

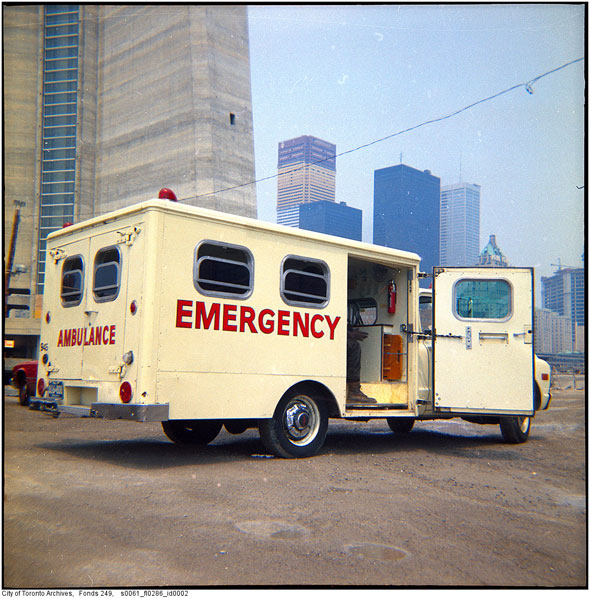

Four nearby workers scrambled to safety up a flight of stairs while others on the lower levels were able to descend. Chemical extinguishers put out the fire while the emergency services were assembling at the base of the tower but the damage was estimated at around $1,000. The four welders workers were treated for smoke inhalation and minor cuts.

The CN Tower was officially completed on April 2, 1975 and opened to the public on June 26. A variety of attractions have been added since: the highest wine cellar in the world, the incredibly unsettling glass floor, and most recently the terrifying EdgeWalk experience.

CN sold its stake in the tower in 1995, prompting a crisis about what CN should stand for now the railways were no longer involved. The new owners opted for the slightly clunky "Canada's National Tower," which is admittedly better than the Canada Lands Company Tower.

Maple Leafs fans hoped the new 16.7 million colour LED light display that adorns the elevator shafts and main pod could be used as a goal light during their heartbreaking and brief cup run this year. No dice, said management. It's Canada's tower - no corporations allowed.

CN Tower Facts

- Total cost: $63 million ($21 million in 1973)

- Height: 553.33 metres (1,815 feet and 5 inches)

- Weight: 117,910 metric tonnes (130,000 tons)

- Concrete: 40,524 cubic metres (53,000 cubic yards)

- Tensioned Steel: 998 kilometres (620 miles)

- Reinforcing Steel: 4,535 metric tonnes (5,000 tons)

- Structural Steel: 544.2 metric tonnes (600 tons)

- Steps to the top: 1,776

- Minutes for a full restaurant revolution: 72

Additional Images

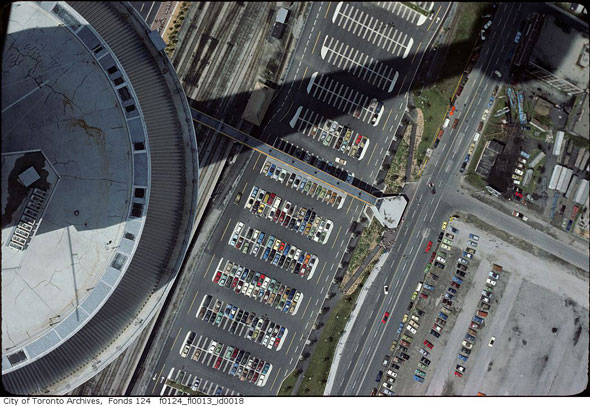

The CN Tower's shadow falls on a surface lot in 1975.

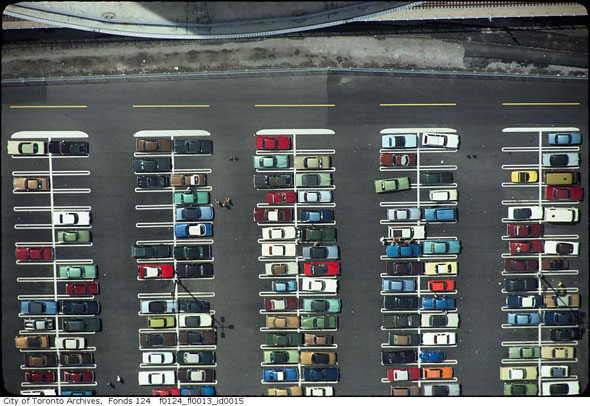

Parking lot at the foot of the CN Tower.

The unfinished CN Tower from the Gardiner.

The construction platform and crane.

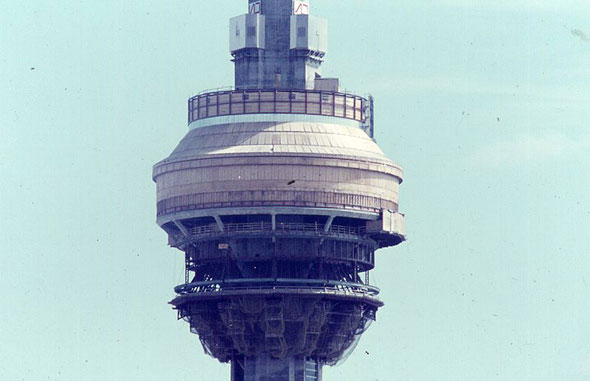

The pod in the early stages of construction.

Construction from the railway lands.

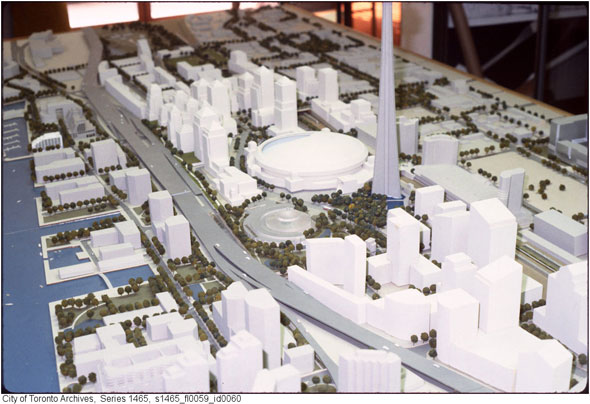

A model showing an early concept for the SkyDome.

The CN Tower with GO trains on the Union corridor.

Grégory Thiell (subsequent photos via the Toronto Archives)

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments