The history of Toronto's first bar and cocktail lounge

There are so many bars and so many different ways to drink in Toronto it's hard to picture the city as a dry town, as it was between 1916 and 1927, or a place where a even an Old Fashioned was a drink too modern to serve in bars.

Then the Silver Rail came along. It was the first bar in the city to get a liquor licence from the LCBO in 1947, and the first to serve anything approaching a sophisticated tipple, legally anyway. Drinking in Toronto would never be the same again.

The province of Ontario has a long and paranoid relationship with alcohol. Decades after prohibition was lifted, the sale of booze was still limited only to those with a valid licence.

A paternalistic "interdiction list" circulated among the LCBO outlets banned people on social assistance and others deemed unsuitable by the province from buying alcohol for home consumption entirely.

Even people off the list were subject to suspicions. Staff were ordered not to serve beer or wine in quantities they suspected were for more than just personal consumption.

Until 1960, it wasn't even possible to pick a bottle of wine off the shelf. The LCBO employed a system similar to the Beer Store experience where staff would pick the desired hooch from a warehouse and bring it to the register.

Though beer had been served in taverns since the 1930s, liquor and mixed drinks weren't readily available, especially not downtown. As John Karastamatis wrote in the Toronto Star, the city didn't just import its alcohol - it had to import its bar staff too when cocktail licences were first allowed under Premier George Drew.

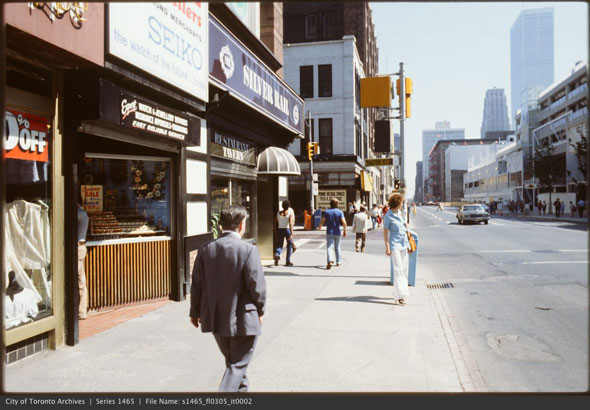

Living under this sourpuss provincial attitude, it's easy to imagine what a revelation the Silver Rail must have been. On the main floor at the northeast corner of Yonge and Shuter, the restaurant housed a spectacular gleaming chrome and neon drinking lounge.

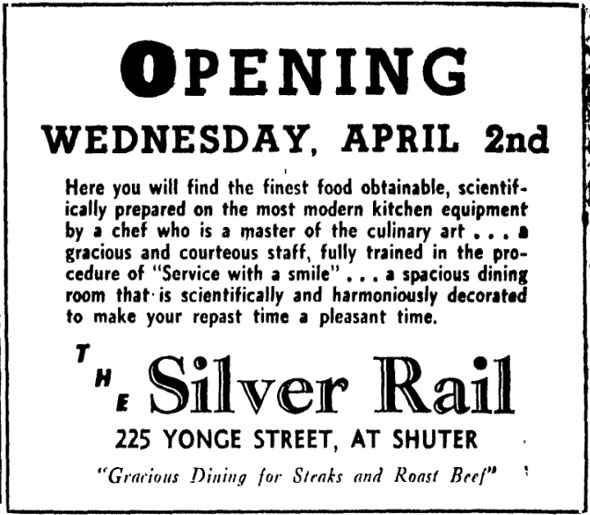

Downstairs, drinkers were served "the finest food obtainable, scientifically prepared on the most modern kitchen equipment, by a chef who is a master of the culinary art," according to the opening announcement.

The interior was modelled after classic New York diners with semi-circular booths and a polished 100-foot bar running the length of the building.

Pink drapes and seat cushions completed the eye-popping look. By comparison, the dining room was relatively restrained with white table cloths and a formal seating arrangement.

The Silver Rail only claimed its status as Toronto's first cocktail lounge by a hair. The Horseshoe Tavern and Club Norman on Adelaide Street East opened close behind and offered similarly dazzling fare.

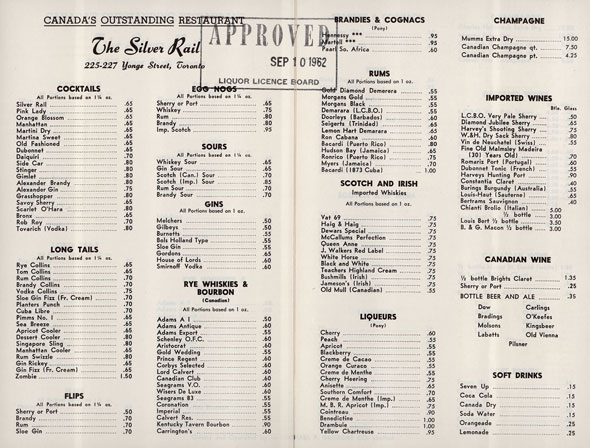

A typical menu at the Rail included whiskies, brandies, champagnes, rums, liqueurs, egg nogs, gins, long tails, flips, and sours. Not bad when you consider that since 1933 booze was limited to beer and the occasional bottle of wine served in basic taphouses.

In its first nine months, the Silver Rail made $90,000 profit. Cheeky ads ran weekly in the Toronto Star telling Torontonians to take a "course" at their "board of education," divorce their wives (from the kitchen), and stop by to listen to the 3 Keyboards house band play "nightly for your listening pleasure."

The lines to get in went around the block despite some decidedly conservative house rules: no women sitting at the bar, and never more than one drink per person on the table.

That first year wasn't without its difficulties - a court dispute between the founders, Louis David Arnold and Michael P Georgas, cleaved the company in half before it reached its birthday.

The pair, former tobacco product manufacturers, both invested $50,000 in the venture and took over the site of the old Muirhead Grill and Cafeteria. Georgas secured the lease while Arnold snagged a lucrative liquor licence in his name - a perfect match.

Things seemed to have turned sour when profits were separated into "bar" and "restaurant," and the paperwork showed the downstairs dining room turning a $6,000 loss.

In ordering the company broken up, Judge Urquhart said he believed Arnold had tried to squeeze out Georgas when it became clear the business would succeed. Dividing up the assets, he cleverly declared, would be like "attempting to separate two eggs in an omelette."

Louis Arnold went on to open Brown Derby, another bar up the street, and the Silver Rail continued to operate under its original name, unchanged, turning out classic cocktails, marinated steaks, and seafood exactly as before.

The business may have cashed in on its novelty early on, but the food was what kept customers returning. Award-winning head chef Domenico Martino worked the kitchens for nine years, becoming one of the first Canadian masters of the trade.

He published two cookbooks, became the editor of the Canadian Restaurant and Hotel Review, and was elected to the elite International Epicurean Circle of London upon his retirement in the late 50s.

The sudden availability of lounge licences begat other bars and gave life to the once-thriving Yonge Street strip around Dundas.

Just down the street from the Silver Rail, the old Scholes Hotel evolved into the Colonial Tavern in 1947 and began serving cocktails too. The business would claim to be the second venue to receive a licence along with several others, but that title had less of a ring to it.

Naturally, for a swinging joint at the nexus of an emerging nightlife scene, the Rail had plenty of notable customers.

Metro Chairman Fred Gardiner liked to drop by for a stuff drink after a hard day plotting expressways, but most notably, on May 15, 1953, jazz legend Charlie Parker took a triple whiskey at the Rail to calm his nerves before joining Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, and Dizzy Gillespie on stage at Massey Hall.

It would be the only time the giants of the genre would appear together on stage, and a seminal moment in music history.

Years later, legendary jazz pianist Oscar Peterson played an impromptu concert on the bar's baby grand piano. Countless actors and sports stars - Bobby Hull to name but one - sipped from a highball on Shuter street during their downtime.

The Brown Derby and Edison Hotel (sadly destroyed by fire in 2011) followed but vanished one by one in the 70s as the neighbourhood turned to retail and sales dropped dramatically.

In 1989 the Silver Rail was nearly banished for good when Famous Players announced plans to open a 2,300-seater theatre in the basement of the Ryrie Building.

Things finally went south in 1998. The building's new owners decided they could make more money with a Bay outlet in the prime Yonge Street storefront and asked the Silver Rail to make way. With nowhere else to go, owner Jim Demeroutis and Nick Yioldassis decided to close.

"This kind of operation belongs in the past," lamented bartender of 43 years Nick Mangos to the Toronto Star. "In the old days the liquor was much cheaper. There was no GST. It's not the same any more. We're all getting older. Every good thing has to come to an end some time ... we've had a lot of great years, a lot of laughs."

City of Toronto Archives, Ontario Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments