Nostalgia Tripping: The Lillian Massey Department of Household Science

A few years ago after a visit to the ROM, the imposing columns of the building across the street caught my eye. Much to my dismay, I read the inscription above the front entrance: DEPARTMENT OF HOUSEHOLD SCIENCE. I sneered and walked away, assuming that the establishment of the faculty devoted to the so-called domestic arts was a type of lip service paid to women entering U of T in increasing numbers, a gender specific subject that must have seemed appropriate to their prescribed role in the early twentieth century.

A book that I came across recently, however, changed my perspective. Anne Rochon Ford's A Path Not Strewn with Roses: Hundred Years of Women at the University of Toronto, 1884-1984, reveals that the building and the faculty it housed played an instrumental role in the life of university women.

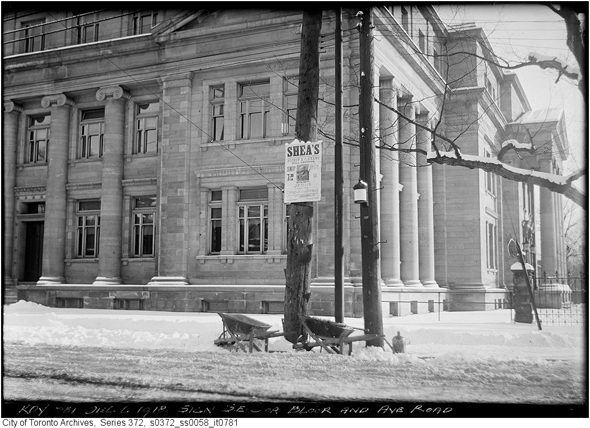

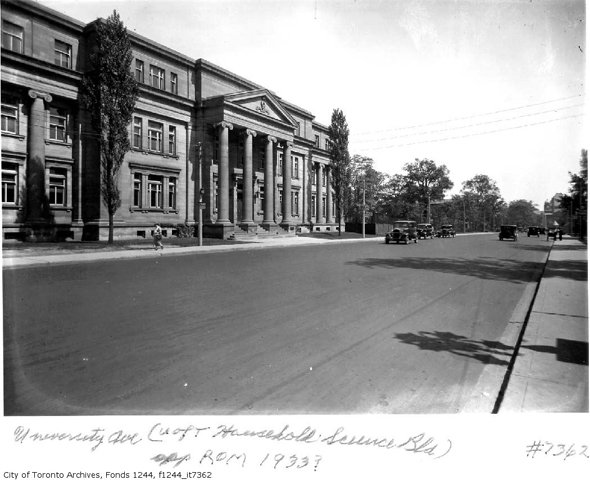

According to Larry Wayne Richards' University of Toronto: An Architectural Tour, George M. Miller designed the structure in the classical style, with the variation of the feminine Ionic order, reflected in the look of the columns. Inside, the pre-Raphaelite stained glass windows located around the main stair hall depict women fulfilling the usual drudgery of household tasks, while the male figures are engaged in hunting and harvesting.

Lillian Massey Treble, a philanthropist, donated half a million dollars toward the construction of the building, which was erected in 1912, on the land owned by Victoria College. Along with Annie Laird, a graduate of household science from the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, she contributed to planning much of the interior of the building. Massey Treble was the daughter of Hart Massey, a philanthropist and industrialist, whose Massey Foundation partly provided funds for the construction of Hart House.

Ford writes that Massey Treble had been successful in establishing household science as a subject in Ontario secondary schools. In 1902, she approached Nathanel Burshwash, the president of Victoria College, who persuaded the U of T Senate to establish a degree program, which came to be known as the Bachelor of Arts in Household Science. In 1907, the Faculty of Household Science was founded. In the same year, Annie Laird, who was appointed as the director, and Clara Cynthia Benson, hired as an instructor of food chemistry and one of the first women awarded a doctorate at U of T, were made Associate Professors, the first female faculty members to be given this title.

The building officially opened in 1913, soon gaining respect as the finest facility in North America. It contained classrooms, laboratories, staff offices, as well as a gymnasium and a pool, the latter of which was located in the basement. These would be the only athletic facilities on campus available to female students. As late as 1972, women were barred from entering Hart House, and the Clara Benson Building, which was later to provide the necessary facilities for women, was not opened until 1959.

The faculty was assessed in 1960s and the university decided to phase it out its program, transferring the staff to the Faculty of Medicine and Faculty of Arts and Science. By this time, many of the courses were being already offered elsewhere on campus, while the aging structure was in need of renovation. As specified in the Massey Treble will, the ownership was transferred to Victoria College.

In 2007, U of T renovated the building, which is recognized as a heritage structure by the City of Toronto. Currently, it houses the Department of Classics and the Centre for Medieval Studies, and, most visibly, a Club Monaco. The former swimming pool is now part of the retail store, and its outline in the floor can still be seen in the basement shopping area. The skylight over it also survives, and it can be seen from the back of the building.

After much thought and research, I feel ambivalent rather than dismissive with regard to the building and what it represents. Although the school provided women with a greater opportunity to enter post-secondary education than was possible elsewhere, it did so within the safe confines of what was regarded as their "proper sphere" for most of the century. The students were taught chemistry, for example, alongside such "subjects" like laundry and cooking. As a part of the history of university women, it seems that the university should have recognized the significance of the structure in a more appropriate way.

Photos from the City of Toronto Archives, Wikimedia Commons, and from the author's collection. I would like to also acknowledge Dr. Robert C. Brandeis of the Victoria University Library for shedding light on the subject of household science.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments