Back to the Portrait at Barbershop

When I first heard the title of the most recent show at Barbershop Gallery, I was both intrigued and a little confused. Named after the group of three artists whose work is featured in the show, it's certainly a mouthful: "The Northern Superlative Order of Wandering Portraitists." As I made my way down to Parkdale, a couple of questions bounced around in my mind. The first: does this "Superlative Order" also have Eastern, Western and Southern divisions? And the second: what are the membership requirements for entry into such an esteemed group?

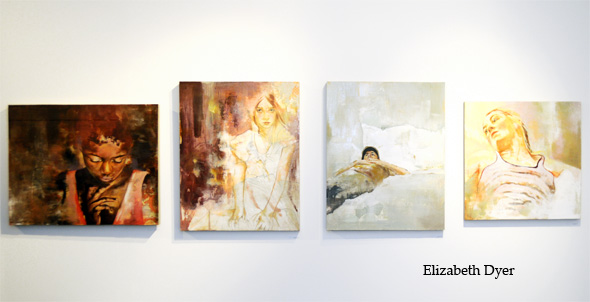

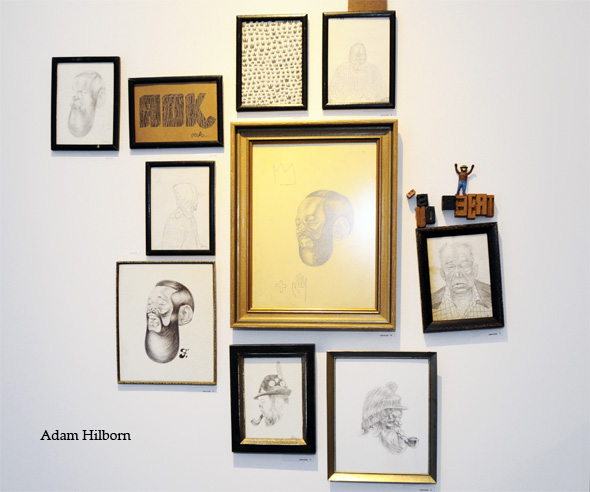

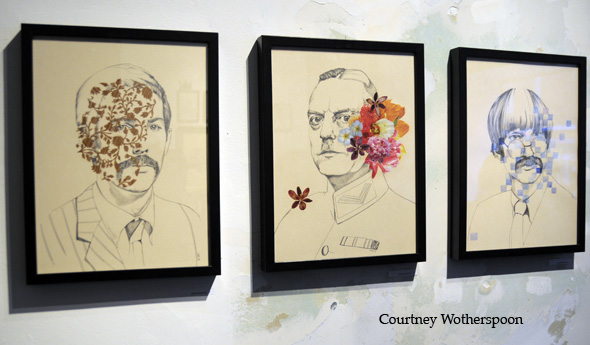

As it turns out, the name is meant to be humorous, if not wholly ironic. And the Northern is, indeed, the only branch of the "Wandering Portraitists." Consisting of Elizabeth Dyer, Adam Hilborn and Courtney Wotherspoon, the label is meant to gesture hyperbolically to their attempt to rethink the portrait as an art form.

As the gallery's blog explains, "each artist's individual approach to portraiture reflects a contemporary alternative to the traditional form. The Superlative Order examines the human condition by returning to conventional methods of drawing and painting, and in doing so, transcends the historically established aesthetic value of portraiture."

If you think that sounds insanely ambitious and somewhat contradictory, I can't blame you. But, like the group's name, caution should be used before taking it all too seriously. And to me, it's a great example of why it's best to let the art do the talking, rather than the written description. After all, who really wants such weighty expectations? I think I could make a pretty compelling argument that not even Picasso transcended "the historically established aesthetic value of portraiture."

But, when viewed in the absence of these "superlatives," a nice thing happens: the art does indeed "speak." Particularly stunning in this sense is Dyer's work, which tends to evoke the forces of memory and nostalgia in equal measure. With their soft backgrounds, and often muted tones, her portraits appear to draw their subjects out of the past in much the same way that the act of memory pulls into focus what was formerly stored in the back of the mind. A prime example of form and content working in unison, they offer a complex consideration of both what and how we remember. Perhaps because of this, I find them vaguely reminiscent of certain works by Paul Klee.

Although different in both choice of media and overall style, Hilborn's work also seems to offer a take on the role that nostalgia plays in portraiture. Working on paper, his portraits of pipe and beard clad males tend to depict their subjects with an eye toward the foundational aspects of their identity, namely masculinity and age. Desaturated and rarely high in contrast, these images suggest men whose best years are almost certainly behind them, but who nevertheless remain undefeated by time.

Wotherspoon's portraits don't fit quite as nicely into my reading of the show's nostalgic commentary. Instead they tend to question the stability of the subject of the portrait in general. Her images appear to begin as works of graphite on paper which then undergo some sort of effacement, be it in the form of collage, watercolour or spray paint. These additional elements subsequently compete with the portrait for the viewer's attention. We never get a completely clear picture of the subject, as is so often the case in reality, despite our desires to the contrary.

The show runs through April 30th, 2009.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments